Though there’s plenty to be pessimistic about in the five months since Turkey’s last parliamentary election in June, the result in today’s repeat snap elections is perhaps the best possible outcome for the various domestic and international actors with a state in Turkey’s continued stability.![]()

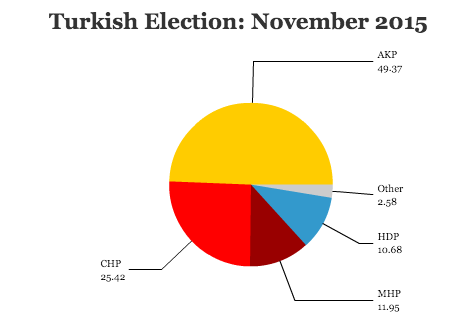

The Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party), the conservative Islamist party that has dominated Turkish politics since 2002, scored the most crushing victory in its history — more than when it initially came to power and more than its prior peak in the 2011 elections. That’s despite a turbulent election campaign marred by an early October suicide blast in the capital city of Ankara, the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of the modern Turkish republic.

Though the AKP will not win the two-thirds majority that it hoped for to enact the constitutional changes that president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan wants to rebalance powers away from the national assembly and to the presidency, the result gives the AKP a clear mandate to govern without seeking a coalition partner. The AKP’s path to a majority victory wasn’t pretty, and there’s a compelling case that Erdoğan has seriously damaged his legacy and, he further undermined the rule of law, fair elections, internal security and press freedom over the past five months. But the victory means that Turkey will not face a third election in the spring and all the destabilization that another months-long campaign period would mean.

* * * * *

RELATED: Ankara bombing curdles already-fraught

Turkish election campaign

RELATED: How the AKP hopes to regain

its absolute majority in November

* * * * *

Most surprisingly, the AKP managed its overwhelming victory while the leftist, Kurdish-interest Halkların Demokratik Partisi (HDP, People’s Democratic Party) still won enough support to win seats in the national assembly. That feels like something of a miracle, given the increasingly tense atmosphere across southeastern Turkey, where polling took place under conditions of near civil war between Turkish military forces and the radical guerrilla group, the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, Kurdistan Workers’ Party).

While HDP leader attorney Selahattin Demirtaş has called for a peaceful approach to the fight for greater Kurdish autonomy, AKP officials, including Erdoğan and prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu have tried to tie the party to the more militant PKK as a years-long ceasefire, the product of advanced peace talks between the Turkish government and PKK leaders, unravelled in July in the wake of a suicide bombing in Suruç (and attributed to the jihadist ISIS/Islamic State/Daesh). Turkey’s hurdle rate for winning seats in the national parliament is 10%. That means, with around 10.6% of the vote, the HDP is entitled to 59 seats, but with just 9.99%, the HDP would have won exactly zero seats. The latter outcome, just five months after the HDP celebrated the first time an expressly Kurdish party won seats in the Turkish assembly, would have greatly undermined Demirtaş’s argument that Turkish Kurds can work through the democratic system for greater autonomy, self-government and other minority rights.

It’s certainly not the outcome Erdoğan would have been hoping for because, had the AKP taken those 59 seats, it would have the elusive two-thirds majority Erdoğan has sought since winning the Turkish presidency last August. In the long run, however, even if Erdoğan dislikes it, it’s much better that the Kurdish minority feels like it can benefit through democratic participation. Continue reading Turkey’s election result the best possible outcome