In central Europe, another German-speaking nation is heading to the polls next month in a race that will likely also result in a broad left/right ‘grand coalition.’![]()

Austria’s parliamentary elections on September 29 will affect a population that’s just two-thirds that of the German state of Bavaria, but the campaign features many of the same dynamics as Germany’s federal elections that will be held exactly one week prior — a broad centrist consensus on economic policy, the likelihood of yet another ‘grand coalition,’ flush economic conditions relative to the rest of Europe and static polls all year long indicating a narrow center-left win.

But there are key differences as well — unlike in Germany, where Christian democratic chancellor Angela Merkel is favored for reelection, it’s Austria’s social democratic chancellor Werner Faymann who will likely return as chancellor. Moreover, there’s a far-right component to Austrian politics that simply doesn’t exist in Germany. While the far-right remains divided among three competing parties (and that makes it unlikely that they will form a government), the far-right parties could cumulative outpoll the center-left and the center-right.

Let’s start with the fundamentals — Austria’s economy grew by an estimated 0.6% last year and 2.7% in 2011, and though its growth this year has been virtually negligible, it dipped into negative growth (-0.1%) for just one quarter (Q4 2012), so it’s difficult to say that Austria has even suffered a recession, at least in technical terms. Although the European Union’s unemployment rate, as of June 2013, remains 10.9% and the eurozone’s unemployment rate an even higher 12.3%, Austria has the absolute lowest unemployment of all 27 EU nations: at 4.6%, Austria’s unemployment is nearly a percentage point lower than the second-lowest, Germany, which has a 5.4% unemployment rate.

That means that the anti-incumbent moods that pushed out French president Nicolas Sarkozy last year and has already weakened his leftist successor, François Hollande, and that upended governments in Greece, Italy, Romania, Bulgaria and elsewhere over the past year, doesn’t have the same punch in Austria.

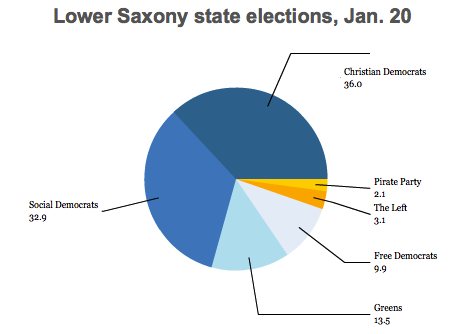

The latest Gallup poll from Austria dated August 22, is representative — it shows that Faymann’s center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ, Social Democratic Party of Austria) holds a narrow lead over its current coalition partner, the center-right Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP, Austrian People’s Party):

The three far-right parties, taken together, however, attract the support of 29% of all Austrian voters — the largest, the Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ, the Freedom Party of Austria), is the longstanding anti-immigrant, anti-EU, extreme-right conservative party in Austria, and it was the party that the late Jörg Haider led controversially into a government coalition in 2000 with the ÖVP.

But Austro-Canadian businessman Frank Stronach, who returned to his homeland last year after decades as chief executive officer of his Ontario-based auto parts company, is leading an alternative populist, eurosceptic right-wing party — Team Stronach — that’s attracting between 8% and 10% of the vote.

Finally, the Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ, Alliance for the Future of Austria), which Haider founded in 2005 when he left the FPÖ, is in danger of losing all of its seats in Austria’s parliament following Haider’s sensational November 2008 death and Stronach’s recent rise.

But most recently, Stronach and the FPÖ leader Heinz-Christian Strache have made more headlines over shirtless photos than policy matters. Furthermore, in March’s local elections in the southernmost state of Carinthia, where Haider had served as governor for nearly a decade, the Freedom Party’s share of the vote dropped from about 45% to just 17%, and the Social Democrats swept to power under its leader Peter Kaiser in alliance with the Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Green Party). Nationally, the Greens are polling at around 15%, which would mark a 40% increase from their 2008 result.

Austrian voters also widely prefer Faymann to continue as chancellor over ÖVP leader and foreign minister Michael Spindelegger — Faymann took over just weeks after the global financial crisis in 2008, and he has pursued one of the most successful center-left policy agendas in Europe. Like in Germany, Austria pursued work-sharing policies (e.g., shorter working hours for everyone) in the immediate aftermath of the crisis to avoid massive layoffs. Faymann’s government has also enacted some of the world’s most successful job training legislation and other forward measures to assist workers remain competitive through Austria’s Arbeitsmarktservice (AMS, Austrian Employment Service): Continue reading In Germany’s shadow, Austria also prepares for late September election