I’ve spent much of the past week traveling through Bretagne (or ‘Breizh’ in the local Breton language) — the peninsula that juts out from northwestern France into the Atlantic Ocean, and I’ve spent some time thinking about regionalism in France and why Bretagne, with its Celtic roots, geographic isolation, historical independence and distinct language, isn’t more like Scotland or Catalonia politically.

With just over 3 million residents, the region of Bretagne is home to about 5% of France’s population, though the administrative region of Bretagne doesn’t include all of what was considered Bretagne historically — another 1 million people live in Loire-Atlantique, which is technically part of the Loire region despite its historical inclusion within wider Bretagne. Regardless of the current regional borders, Bretagne is a unique part of France, and its cultural heritage sets it apart as at least as unique as any other region of France, given that it was settled by Celtic migrants from the north who successfully rebuffed Vikings, Normans, Gauls and Franks for centuries in what, during the Middle Ages, was known as Armorica. Despite its independence, Bretagne increasingly became the subject of both English and French designs in the early half of the millennium, and the region was one of the chief prizes of the Hundred Years War between England and France in the 14th and 15th centuries, which finally settled France’s hold on Bretagne.

Moreover, Breton — and not French — was the dominant language spoken in the region through much of the 19th century. Despite the universal use of French today and a declining number of Breton speakers, around 200,000 native speakers remain, and Breton features prominently on many public signs in the region, especially as you go further west in Bretagne. (Another second language, Gallo, is used by around another 30,000 Breton residents).

Bretons, such as Jacques Cartier, dominated the earliest French efforts to explore and colonize the New World and, even in the 19th century, the region’s role in transatlantic shipping and trade meant that its ties with far-flung places like Newfoundland and Labrador were just as influential as the region’s ties to Paris. Cultural ties with other Celtic regions such as Wales, Scotland and Ireland have long overshadowed French cultural influences as well — Breton music has a distinct character and often features bagpipes not dissimilar to those found in other Celtic folk music traditions.

Furthermore, there’s been a resurgence in interest in Breton heritage and cultivation of Breton language in the past 30 years, even as the number of Breton speakers is set to decline over the next decade to just over 50,000. Its distinctive black-and-white flag, the Gwenn-ha-du, developed in the 1920s during a prior wave of Breton nationalism, flies throughout Bretagne much more prolifically than do other regional flags elsewhere in France.

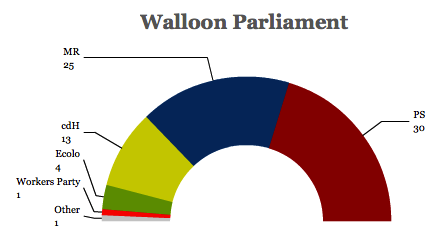

But Bretagne is not a hotbed of separatist agitation like Catalonia or Basque Euskadi in Spain or like Québec in Canada. Nor does it especially have a history of autonomist politics similar to those throughout western Europe — Flanders in Belgium, Galicia in Spain, or northeastern Italy.

Celtic nations, in particular, have long agitated for greater political autonomy throughout western Europe. Scotland will hold a referendum on independence in September 2014, and both Scotland and Wales have routinely supported devolution of power within the United Kingdom. The move for independence in Ireland, another of Bretagne’s Celtic cousins, was perhaps the most successful European nationalist movement in the first half of the 20th century.

The region does have a regionalist party, the Union Démocratique Bretonne (the Breton Democratic Union, or the Unvaniezh Demokratel Breizh in Breton), but the party holds no seats in the Breton regional assembly, and in the most recent 2010 regional elections, it won just 4.29% of the vote. In the June 2012 parliamentary elections to the Assemblée nationale (National Assembly), the UDB’s Paul Molac won election, though technically as a member of France’s Green Party, which contested the elections in alliance with the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) of French president François Hollande.

If there’s any trend worth marking in Bretagne, it’s that the left has done increasingly well in Bretagne in recent years, to the point that Bretagne could even be considered a Socialist stronghold within France. Hollande defeated former president Nicolas Sarkozy in the region by a margin of 56% to 44% in the second round of the May 2012 presidential election and in 2007, though Ségolène Royal lost the presidency to Sarkozy nationwide, she won Bretagne in the second round by a margin of 53% to 47%. Traditionally, the nationalist, far-right Front national of Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen have not succeeded to same degree in Bretagne as they have in other parts of France.

But Bretagne simply hasn’t boasted an incredibly strong politics of regionalism, despite several waves of Breton nationalism throughout the 20th century and the current revival of Breton linguistic and cultural heritage.

Why exactly is that the case?

As you might expect, there’s not a single magic answer, but four factors in particular go a long way in explaining why Bretagne hasn’t developed the same level of regionalist politics as, say, Scotland or Catalonia: the five-century duration of French control over Bretagne, the highly centralized nature of the French government, historical reasons rooted in the 20th century and, above all, the lack of an economic basis for asserting Breton independence.

Continue reading Why isn’t separatism or regionalism more dominant in the politics of Bretagne? →

![]()

![]()