In Belgium, where national and regional elections were largely overshadowed by the simultaneous European parliamentary and Ukrainian presidential elections, Flemish nationalist Bart De Wever is working to assemble a broad center-right government from parties of both of Belgium’s linguistic regions.![]()

Realistically, however, though Belgium’s king Philippe, has given De Wever through tomorrow, June 10, to report back on possible coalitions, there’s a chance that Belgium’s coalition-building process could take months, if not the 541-day ordeal that followed the previous May 2010 national elections.

De Wever’s Flemish nationalist Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA, New Flemish Alliance) emerged as the clear winner of the May 25 Belgian federal elections. It won, by far, the largest share of the vote — 20.26% of the national vote, even though nearly all of it came from Flanders, where it outpolled the center-right CD&V by a margin of 32.22% to 18.47%. De Wever (pictured above), having lost an astonishing amount of weight through diet and exercise since the last election, has given the N-VA a new look, too. While it remains officially in favor of Flemish independence, it’s toned down its support for separation and increased its calls for greater regional autonomy. The N-VA has also enhanced its calls for tax cuts and a trimmer federal and regional budget.

That was enough to put the N-VA in the driver’s seat for the first round of post-election negotiations. Belgium’s king Philippe appointed De Wever as informateur, whose role is to report back to the Belgian king as to potential coalition possibilities. If De Wever can point to a credible governing majority, it’s possible Philippe will appoint him as formateur, officially charging him to form a government.

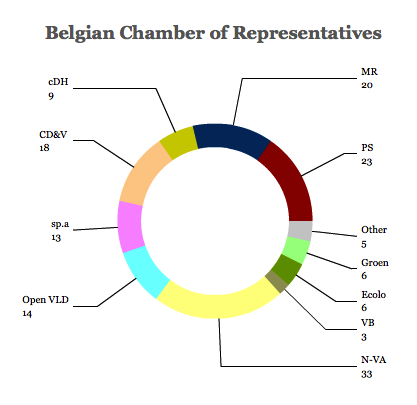

Outgoing prime minister Elio Di Rupo, the head of the French-speaking, Wallonia-based Parti Socialiste (PS, Socialist Party), is not expected to lead a second government, even though his party emerged as the second-largest in the 150-member Chamber of Representatives (Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers/Chambre des Représentants), and the largest vote-winner in French-speaking Wallonia.

Therein lies the awkwardness of the federal negotiations. The largest share of Flemish voters overwhelmingly supported an autonomist, center-right party, while the largest share of Walloon voters supported a federalist, center-left party.

De Wever is working to form a government of both Flemish and Walloon center-right, Christian democratic and liberal parties. But that would require a historic effort, given that Francophone parties have refused to work at the federal level alongside the N-VA in the past. Moreover, any Walloon parties willing to join forces with De Wever could face the wrath of Walloon voters at the next election.

Since the May 25 elections, the shape of Belgium’s regional governments have come increasingly into view, which will in turn influence the national government formation process.

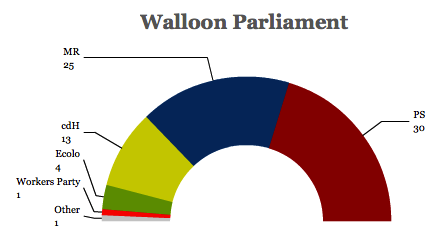

Last week, Di Rupo’s Socialists announced that they would open coalition negotiations with the centrist, Christian democratic Centre démocrate humaniste (cdH, the Humanist Democratic Centre) to form a government in the 75-member regional parliament of Wallonia:

The Walloon deal comes at the expense of the center-right, liberal Mouvement Réformateur (MR, Reform Movement), which made the greatest gains at the regional level, picking up six additional seats and which nearly outpolled the Socialists. The MR’s leaders are already decrying the deal between the Socialists and the cdH, arguing that they instead have the momentum to form a new Walloon government.

The MR’s disappointment is amplified by the apparent coalition deal to lead the Brussels regional government, where the Socialists and the cdH intend to form a government with the Fédéralistes Démocrates Francophones (FDF, Francophone Democratic Federalists), until 2011 part of the MR coalition.

For now, the N-VA will likely become the senior partner in the Flemish government, continuing a partnership with the center-right Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams (CD&V, Christian Democratic and Flemish).

But because of the N-VA’s gains, largely at the expense of the CD&V, it’s unlikely that the CD&V’s Kris Peeters will remain as the minister-president of the Flanders region. Peeters and the N-VA’s Geert Bourgeois, who has served as vice-minister-president under Peeters since 2009, are leading the current negotiations for the Flemish government.

So what does all of this mean for the federal negotiations? Continue reading De Wever gets first shot at forming Belgium’s next government