When Dutch voters go to the polls on September 12, we don’t know whether they’ll favor prime minister Mark Rutte’s Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) or Emile Roemer’s Socialistische Partij (SP, the Socialist Party) or even Diederik Samsom’s Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA, the Labour Party) as their top choice.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

What we do know is that the election could well be the worst post-war finish for the traditional Christian Democratic party in the Netherlands, the Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA, Christian Democratic Appeal). It’s currently on track to finish in fifth place (or even sixth place) in a country that it had a hand in governing virtually without break in Dutch post-war politics until 2010.

In 2010, the CDA won just 21 seats in the lower house of the Dutch parliament, and it could win just 15 seats or less this time around.

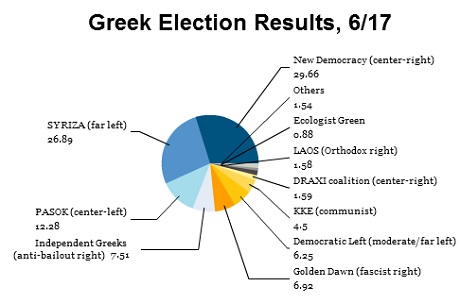

So it goes all across Europe:

- In Italy, the Democrazia Cristiana controlled the government (or participated in governing coalitions) for nearly 50 years of post-war Italian politics. The Tangentopoli (‘Bribesville’) scandal led to its demise under the weight of massive corruption allegations in 1992, and the remaining core of that party, the Unione dei Democratici Cristiani e di Centro (UDC, the Union of Christian and Centre Democrats), led by Pier Ferdinando Casini, plays a significant, but minor role in Italian politics today.

- Norway’s Christian Democratic Party, the Kristelig Folkeparti (KrF) once dominated Norwegian politics as well, but now holds just 10 out of 169 seats in the Norwegian parliament.

- In Bavaria, the Christlich-Soziale Union (CSU, Christian Social Union) has controlled Bavaria’s state government since 1957. It’s still the overwhelmingly largest party in Bavarian politics, but it lost 32 seats in the Landtag in 2008 and now holds just 92, and it looks likely to lose even more seats in the Bavarian state elections that must be held in 2013.

- In Switzerland, the Christlichdemokratische Volkspartei der Schweiz (CVP, Christian Democratic People’s Party of Switzerland) has steadily declined since the 1970s.

Only in German federal politics does Christian democracy seem to be holding on — in the form of Angel Merkel’s Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union), which is allied at the federal level with Bavaria’s CSU.

So what’s happened to Christian democracy? And is it a concept whose time is up?

Christian democracy emerged as a political movement in the 19th century, as much as anything a reaction of the Catholic Church to the Industrial Revolution — and to the Marxist ideas that had so effectively challenged industrial capitalism in the mid-19th century, in the same way that the social democratic movement that gave voice to (and moderated) the growing labor movement. (Some political scientists see a parallel in the “justice and development” strand of moderate Islamist parties that have emerged in Turkey and through vehicles like the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Jordan).

It reached its heyday during the Cold War as a bulwark against the communist influences of Soviet Russia, but today seems increasingly an anachronism as the European right divides into, on the one hand, a free-market liberal ideology untroubled with cultural issues and, on the other hand, a nationalist ideology that is increasingly both anti-Europe and anti-immigrant. That fragmentation provides yet another complication in navigating the European Union out of its current debt and currency crisis — the European Union was formed and the eurozone conceived in a world where Christian democracy largely controlled the initial EU member states. Continue reading Is the European ‘Christian democracy’ party model dead?