Ireland’s feisty voters, which have developed an art form out of defeating European Union treaties, still seem likely to support the fiscal compact treaty in Thursday’s referendum:![]()

Polls show the ‘yes’ vote in the lead — the latest Irish Times poll shows 39% in favor, 30% opposed, with 22% undecided and 9% not voting. Other polls have shown even strong support for the ‘yes’ camp.

After the Sturm und Drang of May 2012’s electoral wave, which has seen voters support anti-austerity politicians from Germany to Greece, the fiscal compact seems to have less momentum than ever.

So it would be a plucky twist of fate if Ireland, which has become the bête noire of EU treaty making — its constitution provides that a EU treaty is an amendment of the Irish constitution and, consequently, must be approved in a referendum — gives a thumbs-up to a fiscal compact that might never go into law EU-wide and would result in a loss of Irish sovereignty with respect to its own fiscal policymaking.

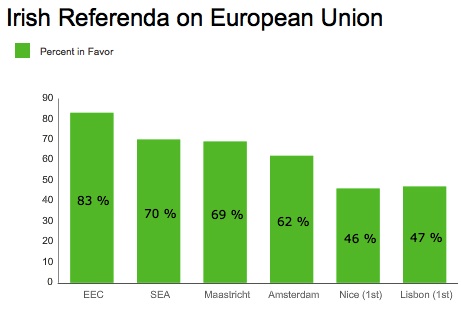

Furthermore, over the course of Ireland’s four decades in the EU, Irish voters have voted on six treaties, and in each case, the initial pro-treaty vote has decreased for each new treaty:

In each of the last two efforts, for the Treaty of Nice in 2001 and the Treaty of Lisbon in 2008, Irish voters initially defeated the treaty, Irish negotiators worked to attain new concessions from the EU and each treaty was subsequently ratified in a second referendum.

The fiscal compact, cobbled together by Merkel and then-French president Nicolas Sarkozy in December 2011 amid soaring bond prices for Spanish and Italian debt, would limit each EU member state to a structural budget deficit of just 0.5% of GDP. That target seemed unrealistic in November, but seems even more so today, with many European economies still stagnant (or in recession). Newly elected French president François Hollande has called for revisiting the terms of the fiscal compact during and after his election.

So the final ratification of the fiscal compact is far from certain, with or without Ireland. As the UK and the Czech Republic opted out of the fiscal compact, the fiscal compact is not, as a technical matter, a formal EU treaty. Accordingly, it needs ratification from just 12 eurozone members before January 1, 2013 to go into effect.

As of today, it has received just three conditional ratifications. In Slovenia and Portugal, national parliaments have approved the fiscal compact, but the ratifications are not formally complete without presidential approval. The only other country to ratify the fiscal compact is Greece, whose May parliamentary elections were so inconclusive that the country must hold a second set in June, which could very well result in electing Europe’s most anti-austerity government.

So why, in the face of so many reasons to junk the fiscal compact, which may not even be ratified by the rest of Europe, are Ireland’s voters set to approve it on Thursday?

The ratification process means that an Irish ‘no’ vote would not, in itself, prevent the treaty from going into effect. This would deprive Ireland’s ability to hold-up the treaty for new concessions a la Nice and Lisbon. So, many Irish voters might say, why bother holding out for more renegotiation, especially when the chances of the fiscal compact’s becoming law seem less likely than ever?

But there’s an even better reason — a ‘no’ vote would cause much more harm than it would to the EU. Irish voters understand that a ‘no’ vote could spike bond prices, making borrowing costs even more difficult for Ireland. The nation has received significant financial assistance from Europe since the 2008 financial crisis, after which Ireland nationalized the debts of its insolvent banks. A ‘no’ vote would likely close off access to the ESM and also scare foreign investors from lending money in the future, as noted in The Financial Times:

Most investors expect the vote to pass and point out that, despite yields creeping up recently, Ireland seems to have decoupled to a degree from the rest of the eurozone periphery. Indeed, Dublin’s stock exchange is one of the few in Europe that has not given up all its early-year gains.

“A pragmatic but unhappy Yes vote is the likely outcome for the referendum,” says Paul Griffiths, head of fixed income at Aberdeen Asset Management.

It’s a kind of financial blackmail, perhaps, but it explains why the campaign has been fairly subdued — pro-treaty forces seem to have held a slight or moderate lead since the referendum was announced in March.

Ireland’s Taoiseach Enda Kenny and his center-right Fine Gael party, as well as his center-left coalition partner, the Labour party, are in favor of the treaty. So is Fianna Fáil, the center-right party of opposition. Sinn Féin and the Socialist Party remain the only major Irish parties opposed to the treaty.

The latest controversy over the treaty has resulted from a snit over Kenny’s refusal to engage in a debate over the treaty, leading to what I think must be the best insult of the campaign so far:

“And everybody knows that Enda couldn’t negotiate his way out of a wet paper bag.”

Maybe.

But it looks like he’ll be the first Irish Taoiseach to win a referendum on an EU treaty for the first time in 15 years.

One thought on “Irish set to approve fiscal compact in Thursday referendum”