The United States doesn’t typically like to hand gifts to Hassan Nasrallah, the longtime leader of Hezbollah, the Shi’a militia that remains a key player not only in the domestic politics of Lebanon, but throughout the Middle East.

But when news broke last Friday that U.S. president Barack Obama was preparing U.S. assistance to arm Syrian rebels in their fight against Syrian strongman Bashar al-Assad, that’s in effect what the United States has done by broadening the two-year civil war in Syria, a conflict that neighboring, vulnerable Lebanon has largely managed to avoid in the past two years.

Hezbollah’s recent military mobilization against the mostly Sunni rebels, however, in support of Assad, was already rupturing the national Lebanese determination to stay out of the conflict. The U.S. announcement of support for the rebels, however tentative, gives Hezbollah a belated justification for having expanded its own military support to Assad, and risks further internationalizing what began as an internal Syrian revolt against the Assad regime.

The U.S. decision to support anti-Assad rebels

The United States is signaling that it will provide small arms and ammunition to only the most ‘moderate’ of Syria’s rebels, though not the heavier anti-aircraft and anti-tank weaponry that rebel leaders have said would make a difference. But even if the Obama administration changed its mind tomorrow, the damage will have already been done in the decision to back the largely Sunni rebels. No matter what happens, Hezbollah will now be able to posture that it’s fighting on behalf of the entire Muslim world against Western intruders rather than taking sides in a violent sectarian conflagration between two branches of Islam.

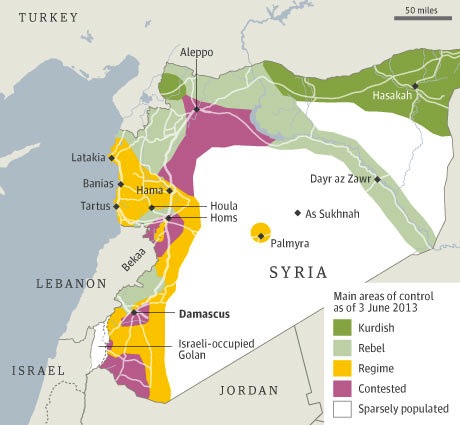

Supporters of U.S. intervention credibly argue that Hezbollah’s decisive intervention earlier in May and in June in Qusayr, a town in western Syria, led to an Assad victory that will inevitably make Syria’s civil war longer and deadlier. Hezbollah’s decision to intervene on behalf of Assad was a key turning point that marked a switch from indirect and clandestine support to becoming an outright pro-Assad belligerent in Syria, which brings tensions ever closer to exploding in Lebanon. Furthermore, Russian support for Assad, Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s increasingly strident opposition to Assad, as well as implicit Iranian support for Hezbollah, means that Syria is already a proxy for geopolitical positioning, whether U.S. policymakers like it or not.

But that doesn’t mean that the active support of the United States will suddenly make things better in Syria — after all, the United States has a controversial track record over the past decade in the Middle East. It’s winding down a 12-year war in Afghanistan that, though it pushed the Taliban from power within weeks in 2001, has done little to establish lasting security or foster a truly national government. Its 2003 invasion of Iraq, which toppled one of the two Ba’athist regimes in the Middle East in removing Saddam Hussein from power, and the subsequent U.S. occupation still failed to prevent vicious Shi’a-Sunni sectarian fighting that approached the level of civil war between 2006 and 2008 and that still simmers today.

It’s the same familiar kind of bloody sectarian violence that now features in Syria, the remaining Ba’athist regime in the Middle East.

Moreover, the risks to Lebanon are now even more staggering. Lebanon, which had been set to hold national elections last weekend on June 16, has instead postponed those elections indefinitely, because negotiations among Lebanon’s various religious confessional groups to draft a new election law have taken a backseat to the more pressing task of keeping the country together.

The U.S. came to its decision in light of a determination that Assad had used chemical weapons against at least a small segment of the rebels, thereby crossing a ‘red line’ that Obama established in August 2012 in the heat of the U.S. presidential campaign last year. But as The Washington Post‘s Ernesto Londoño reported last week, U.S. advisers had already been working quietly with Jordanian officials for months in order to reduce the chances that Syria’s stockpiles of chemical weapons will fall into misuse by either the Assad regime or by the opposition.

It still remains unclear just what the Obama administration believes is the overwhelming U.S. national interest in regard of Syria — though the Assad regime is brutal, repressive and now likely guilty of war crimes, there’s not necessarily any guarantee that a Sunni-dominated Syria would be any better. Last Friday, U.N. secretary-general Ban Ki-moon indicated that he opposes the U.S. intervention in Syria because it risks doing more harm than good.

As Andrew Sullivan wrote in a scathing commentary last week, the forces that oppose Assad are a mixed bunch, and there’s no way to know who exactly the United States is proposing to arm:

More staggeringly, [Obama] is planning to put arms into the hands of forces that are increasingly indistinguishable from hardcore Jihadists and al Qaeda – another brutal betrayal of this country’s interests, and his core campaign promise not to start dumb wars. Yep: he is intending to provide arms to elements close to al Qaeda. This isn’t just unwise; it’s close to insane….

Do we really want to hand over Syria’s chemical arsenal to al Qaeda? Do we really want to pour fuel on the brushfire in the sectarian bloodbath in the larger Middle East? And can you imagine the anger and bitterness against the US that this will entail regardless? We are not just in danger of arming al Qaeda, we are painting a bulls-eye on every city in this country, for some party in that religious struggle to target.

I understand why the Saudis and Jordanians, Sunni bigots and theocrats, want to leverage us into their own sectarian warfare against the Shiites and Alawites. But why should America take sides in such an ancient sectarian conflict? What interest do we possibly have in who wins a Sunni-Shiite war in Arabia?

The ‘rebels’ are, of course, a far from monolithic unit — the anti-Assad forces include all stripes of characters, including the Free Syria Army, a front of former Syrian army commanders dismayed at Assad’s willingness to commit such widespread violence against the Syrian people, but also including more radical Islamist groups such as the Syria Islamic Front, the Syria Liberation Front and even groups with non-Syrian leaders with global links to al-Qaeda, such as Jabhat al-Nusra, which is comprised of radical Salafists who want to transform Syria into an Islamist state.

Liberal interventionism strikes again

When Obama announced earlier this month that he was promoting Susan Rice as his new national security adviser and Samantha Power as his nominee to be the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, I argued that it was a victory for liberal interventionists within Obama’s administration and that it could mean that the United States takes a stronger humanitarian interest in Syria. Many other commentators, such as Wonkblog‘s Max Fisher, downplayed that possibility, arguing that their promotions meant ‘not much’ for U.S. policy on Syria, and that ‘there is good reason to believe that Power and Rice are not about to change U.S. policy in Syria.’

That, of course, turned out to be a miscalculation. Less than 10 days after the Rice/Power announcement, the Obama administration is now ratcheting up its involvement in the Levant on a largely humanitarian, liberal interventionist basis, with the plausible possibility that a U.S.-supported no-fly-zone could soon follow.

The key fear is that the Obama administration’s ‘humanitarian’ response may result in an even more destabilizing effect on Lebanon. Continue reading U.S. move to support anti-Assad allies jeopardizes Lebanon’s stability →

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()