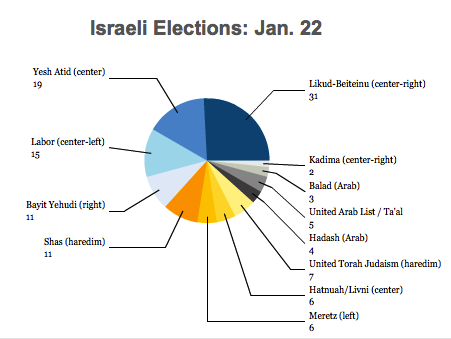

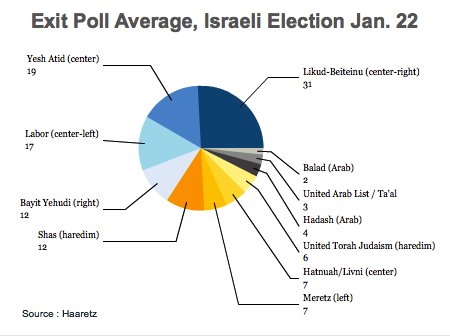

The news out of Israel throughout election day — now confirmed by preliminary exit polling — is that Yair Lapid (pictured above) and his new party Yesh Atid (יש עתיד, ‘There is a Future’) have performed significantly better than expected, making it the second-largest party in the Knesset (הכנסת), Israeli’s unicameral parliament.

As I wrote yesterday, prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu will have some difficult choices to make in determining how to cobble together a majority coalition of at least 61 members of the Knesset — Lapid is now certain to be a major factor in Netanyahu’s negotiations.

So it’s worth taking a little time to focus on what Lapid has apparently accomplished and what he’s focused on in the campaign.

Lapid entered politics in Israel only in January 2012, and amid rumors that Netanyahu would call snap elections in April 2012, hastily named his party ‘Yesh Atid.’ But he’s long been a well-known figure in Israeli public life, first as a well-regarded columnist in the 1990s and then as a television anchor and talk-show host.

He’s also pretty easy on the eyes.

On the campaign trail, he’s gone out of his way to describe Yesh Atid as a center-center party:

Ideally, Yair Lapid’s self-described “Center-Center” party should present the perfect balance between the Right and Left blocs that this country needs so desperately. The danger though, is that Yesh Atid is just another example of a neither-here-nor-there party that is doomed to fail like so many centrist platforms before it.

For now, Netanyahu must realize that it means that Lapid would be more likely than Labor (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית) or Meretz (מרצ, ‘Energy’) to support planned budget cuts, in light of a growing budget deficit (over 4% in 2012). That will be good news for Netanyahu regardless of whether Yesh Atid joins the next government.

In many ways, Yesh Atid has replaced Kadima (קדימה, ‘Forward’), the centrist party that Ariel Sharon founded and that is projected to have lost all 28 of the seats it held in the prior Knesset.

Notably, Lapid’s father, Tommy Lapid, who died in 2008, was also a journalist who also entered politics later in life — he became party chair of the secular, liberal Shinui (שינוי, ‘Change’) Party in 1999 and won a seat in the Knesset and six seats.

In the 2003 elections, however — a decade ago — Tommy Lapid’s Shinui broke through with 15 seats, making it the third-largest party in the Knesset and a victory, like today’s victory for Yesh Atid, for secular Israel over the ultraorthodox parties. After that election, Tommy Lapid joined the government of Ariel Sharon as deputy prime minister and minister of justice, although Tommy Lapid and Shinui ultimately left the government in 2004 over disputes with the more conservative ultraorthodox members of Sharon’s coalition. As the 2006 elections approached, infighting within the party led to Shinui’s loss of all 15 seats, however.

In 2012 and 2013, his son Yair Lapid has also brought a secular centrist sensibility to the campaign trail:

Lapid is perceived as the “least left” in the political bloc that extends from Netanyahu to Hanin Zuabi. He has no personal or ideological feuds with the prime minister, as do most of the other candidates. A two-digit number of seats could enable him to hook up with Netanyahu as a replacement for Shas, and reduce the price the Likud would have to pay the Haredim.

Lapid is touting himself as a candidate for education minister, and even now his background as a volunteer civics teacher stands out. He could even learn a thing or two from the outgoing minister about how to exploit the ministry for self-advancement: Gideon Sa’ar bought the silence of the teachers’ unions that had made life hell for his predecessors, and focused on politicizing the system and making headlines, which turned him into the right’s chief ideologue and the winner of the Likud primary.

Given his apparent success today, Lapid may want to hold out for a position bigger than just education minister. Continue reading Who is Yair Lapid? →

![]()