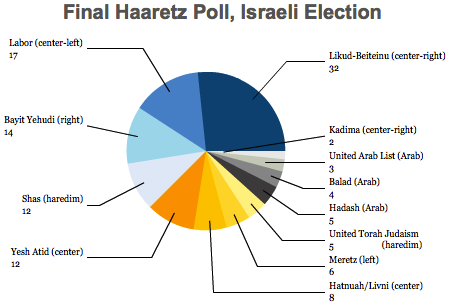

While Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu contemplates the rise of his former protégé-turned-rival Naftali Bennett, leader of the surging conservative Bayit Yehudi (הבית היהודי, ‘The Jewish Home’), he’s probably still not too worried about his chances to return as Israeli prime minister after January 22’s elections to the Knesset (הכנסת), Israel’s 120-seat unicameral parliament.

That’s because he’ll have his pick of any number of orthodox or conservative parties to bolster his own conservative Likud (הַלִּכּוּד, ‘The Consolidation’), which — for the purposes of this month’s election, at least — has partnered with the secular nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu (ישראל ביתנו, ‘Israel is Our Home’) of former foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman, who recently resigned in light of an indictment on charges of breach of public trust.

But, even more, it’s also because the remaining center-left opposition to Netanyahu is horribly fractured in at least five different groups:

- the centrist Kadima (קדימה, ‘Forward’) of former prime minister Ehud Olmert;

- Hatnuah (התנועה, ‘The Movement’), a new party formed by former foreign minister Tzipi Livni, who lost the Kadima leadership in March 2012;

- the longtime center-left Labor (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית) party, led by the more leftist Shelly Yacimovich since 2011;

- Yesh Atid (יש עתיד, ‘There is a Future’), a vaguely reformist center-left party formed this year by former television news anchor Yair Lapid; and

- Meretz (מרצ, ‘Energy’), Israel’s far-left, social-democratic Zionist party.

Together, conceivably, they could have united to form an anti-Netanyahu coalition. In the span of one week, as it turns out, Livni has gone from public musing about joining Netanyahu’s next coalition to calling for one last attempt, with 18 days to go until the election, at a united front. Livni’s tenure as foreign minister featured lengthy negotiations with the Palestinian Authority over a potential Israeli-Palestinian peace plan, though Netanyahu has reassured Likud colleagues that Livni won’t serve as foreign minister, even if Lieberman remains too beleaguered by legal problems to resume his role.

With the exception of Labor, which has pushed a much more economically liberal platform than the other centrist parties, it’s hard to believe that the failure of the center-left has more to do with arrogant personalities than it does with real ideological differences.

At the heart of the center-left’s dilemma is the disintegration of Kadima, the party established by former prime minister Ariel Sharon in 2005 to give him the political space necessary to begin dismantling Israeli settlements in the West Bank and engage the Palestinian Authority in serious peace talks. At the time, Kadima drew support from prominent Likud members as well as from senior Labor figures as well, including, notably, Shimon Peres, who now serves as Israel’s president.

But Kadima’s power started leaking away with the stroke in January 2006 that incapacitated Sharon by leaving him in a permanent coma.

His successor as prime minister, Ehud Olmert (pictured above, with Livni), left office in 2009 under a cloud of scandal and although he was largely acquitted of corruption charges earlier this year, state prosecutors are appealing the acquittal, so Olmert’s not completely out of legal trouble.

In the previous 2009 Knesset elections, Livni, who served as deputy prime minister to Olmert as well as foreign minister, led Kadima admirably enough, winning the highest number of seats in the Knesset (28 to Likud’s 27). But Netanyahu ultimately formed a governing coalition with other allies (including Labor which, at the time, was led by former prime minister and defense minister Ehud Barak). Livni refused to join that coalition, and so Kadima went into opposition.

Fast forward to early 2012. Kadima MKs, disgruntled with Livni’s performance, replaced her as leader with Shaul Mofaz, who served as Sharon’s defense minster earlier last decade. Mofaz, after initially refusing to join Netanyahu’s coalition, promptly did so in May, only to leave the coalition in August over disagreements over the Tal Law. Mofaz, in making such a hash of coalition politics, managed to worsen Kadima’s already precarious electoral position.

Livni promptly resigned from the Knesset in a bit of a huff, returning to politics only last month when she formed Hatnuah, which in English is literally known as ‘The Tzipi Livni Party.’ Ideologically speaking, it’s difficult to see much daylight between her views and Kadima’s views or even Lapid’s views.

While Olmert’s legal troubles may have stopped him from running in this month’s elections himself, it certainly hasn’t stopped him from making mischief — earlier this week, he in no uncertain terms urged Israeli voters to support Kadima rather than his one-time deputy Livni:

Speaking at an event for Kadima mayors in Ramat Gan, Olmert sang the praises of current Kadima chairman Shaul Mofaz and mocked The Tzipi Livni Party’s slogan.

“I hear that the hope will vanquish the fear,” Olmert said. “That is indeed a nice slogan, and I am not against slogans. But what is the practical content behind it? If there is anyone who has already proven that he knows how to defeat fear in the streets and provide security and hope to the citizens of Israel, it is the man who, as IDF chief of staff, commanded Operation Defensive Shield and defeated the second intifada.”

Olmert was even harsher at an event in late December:

“She lost the party leadership by a huge margin, because when she headed the party its members lost trust in her,” Olmert said.

“That is the truth. She did not succeed as head of the opposition.”

The change of heart is fascinating, given that just two months earlier, the two former Kadima leaders seemed much more in concert about uniting against Netanyahu, releasing a joint statement on October 31 indicating they would both return to politics as a united force.

Clearly, no longer. Continue reading Olmert’s break with Livni further fragments Israel’s center-left opposition →

![]()