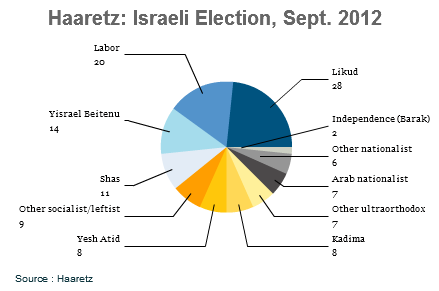

Foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman was once so close to Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu that the two political leaders joined forces to fight the 2013 elections on a joint ticket. When Lieberman stepped down as foreign minister in 2012 pending resolution of charges of fraud and breach of public trust, Netanyahu held the foreign affairs portfolio himself, with every intention of re-appointing Lieberman to the position when Lieberman was subsequently cleared of the corruption-related charges.![]()

That makes it all the more spectacular that Lieberman announced Monday that he was resigning his office and that his party, the secular nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu (ישראל ביתנו, ‘Israel is Our Home’), would not be joining Netanyahu’s next governing coalition, throwing the prime minister’s plans for a third consecutive term into disarray.

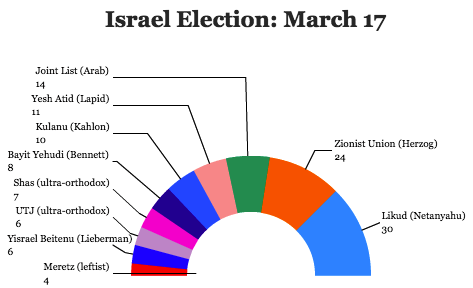

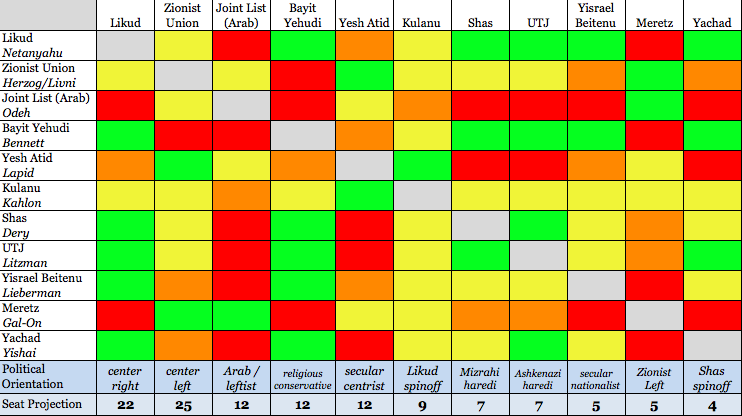

With 48 hours to go before Netanyahu has to assemble a government, he now has to deal with the loss of six seats that have reduced his expected coalition to a bare majority of 61 of the Knesset’s 120 seats — not to mention a sudden fight to replace Lieberman as foreign minister. Netanyahu’s decision, rushed though it may be, will set the tone for Israel’s troubled relations with the United States and with Europe. Moreover, without Yisrael Beitenu, Netanyahu’s government could collapse on the whim of a single MK, including hard-line allies on the Israeli right.

* * * * *

RELATED: Netanyahu set for six-party, right-wing coalition

RELATED: Israeli election results —

eight things we know after Tuesday’s vote

* * * * *

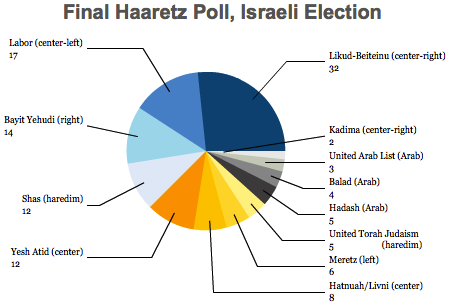

That’s renewed the growing speculation that Netanyahu might be forced, either now or in coming months, to seek a national unity government with the largest opposition party, the Zionist Union (המחנה הציוני), a coalition between the center-left Labor Party (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית) and a bloc of moderates led by former justice minister Tzipi Livni. The Zionist Union’s leader Isaac Herzog reiterated his refusal, however, to join a Netanyahu coalition. Though Netanyahu won a two-week extension to form a government from Israeli president Reuven Rivlin in late April, Herzog will likely have his chance to form a government if Netanyahu fails to do so before the May 7 deadline.

Lieberman, for what it’s worth, blamed Netanyahu’s concessions to the haredi parties that seek the repeal of laws passed by secular lawmakers in the prior government to reduce military exemptions for ultraorthodox students and liberalize marriage laws, which made official Jewish weddings much easier for Russian immigrants who vote for Yisrael Beitenu. Lieberman also challenged Netanyahu’s toughness on Gaza, and he bemoaned the way that Netanyahu and allies abandoned a controversial bill to proclaim Israel a ‘Jewish state.’ Many commentators in Israel were quick to ascribe more cynical motives to Lieberman, who had once harbored dreams of succeeding Netanyahu as prime minister, and Likud officials vented their fury with Lieberman. Continue reading Lieberman resignation rocks Israeli coalition talks