Daniel Levy, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at the European Council on Foreign Relations, has written in Foreign Policy what’s perhaps the best piece I’ve read in the U.S. media — or the Israeli media, for that matter — on next Tuesday’s upcoming Israeli elections, where he makes the point that Israeli politics has become both incredibly fragmented and ossified:

Alongside [Naftali] Bennett’s rapid rise, Jan. 22 is best understood as a “Tribes of Israel” election — taking identity politics to a new level. Floating votes may exist within the tribes of Israel, but movement between tribes, or political blocs, is almost unheard of. Israelis seem to relate their political choices almost exclusively to embedded social codes rather than contesting policies.

By Levy’s estimation, although voters may swing from party to party within a larger bloc, most Israeli voters remain within one of four essential ‘tribes’:

[Prime minister Benjamin] Netanyahu’s Zionist right (including the far right and national religious right), [former foreign minister Tzipi] Livni’s Zionist center (only Meretz still defines itself as Zionist left), the ultra-Orthodox bloc, and the bloc overwhelmingly representing Palestinian Arab citizens.

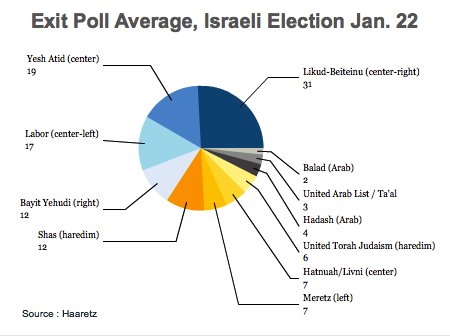

Not so long ago, you could make the credible argument that Israeli politics was essentially a two-party democracy, with the center-right Likud (הַלִּכּוּד, ‘The Consolidation’) of figures like Yitzhak Shamir and Menachem Begin and the center-left Labor (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית) — and from the 1960s through the end of the 1980s, the ‘Alignment’ (המערך) — of figures like Golda Meir, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres.

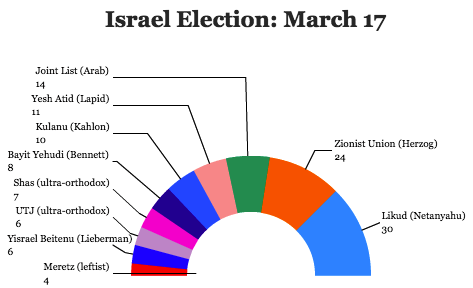

Sure, there were third parties and ultra-orthodox and Israeli Arab parties back then, too, but Likud and Labor/Alignment would often win two-thirds or more of the seats in the Knesset (הכנסת), Israel’s unicameral parliament. In the most recent 2009 Israeli elections, however, Likud and Labor won a cumulative 40 seats — exactly one-third of the Knesset, and given the proliferation of personality-based parties in Israeli politics, it’s clear that Israel has moved to a system with much less long-term party affiliation and discipline.

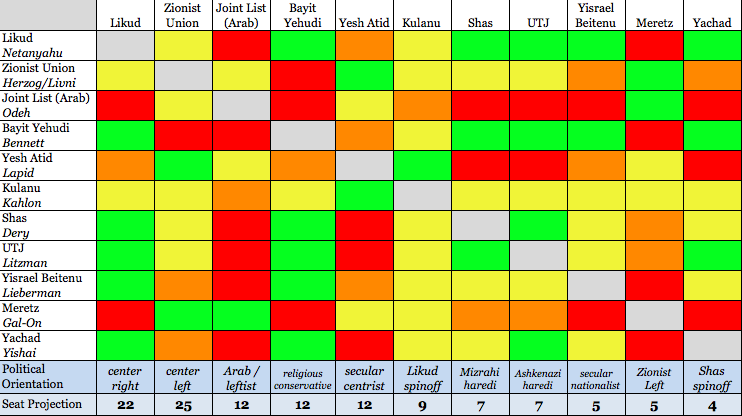

As Levy makes demonstratively clear in his piece, however, each of his four identified ‘tribes’ contain multiple parties:

- The ‘Zionist right’ includes not only Likud and its campaign partner, the secular nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu (ישראל ביתנו, ‘Israel is Our Home’) that appeals especially to Russian Jewish immigrants and is led by former foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman, who has resigned in light of ongoing legal troubles, but also Bennett’s upstart, conservative Bayit Yehudi (הבית היהודי, ‘The Jewish Home’).

- The ‘Zionist center-left’ is more or less hopelessly fragmented into five parties — Labor, under Shelly Yacimovich, which is pushing economic issues in this election; Livni’s new party, Hatnuah (התנועה, ‘The Movement’), which is pushing mainly Livni in this election; Livni’s old party, the now-hemorrhaging Kadima (קדימה, ‘Forward’); Yesh Atid (יש עתיד, ‘There is a Future’), another personality-based party formed in 2012 by former television news anchor Yair Lapid; and Meretz (מרצ, ‘Energy’), the only truly leftist party in Israel with any remaining strength.

- the ultra-Orthodox, or the haredim, the most conservative (in this case, religious conservatism, not necessarily political) followers of Judaism, including both the Middle Eastern sephardim that back the largest of the haredi parties, Shas (ש״ס) and Am Shalem (עם שלם, Whole Nation), a breakaway faction from Shas, as well as the Central and Eastern European ashkenazim that back the United Torah Judaism (יהדות התורה המאוחדת) coalition.

- the Israeli Arabs, which include three parties that are each expected to win a handful of seats in the Knesset — Balad, Hadash and the United Arab List-Ta’al.

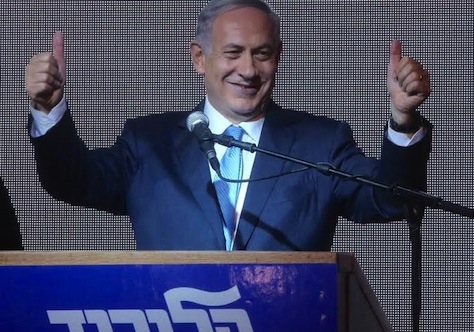

A look at the recent polling bears out Levy’s thesis — there’s a shift away from the ‘Likud Beiteinu’ alliance and a shift toward the Jewish Home, and there’s a massive shift away from Kadima in favor of Livni’s party, Labor and Yesh Atid. By and large, however, the ‘right/religious’ seats would go from 65 to 67, and the ‘center/left/Arab’ seats would go from 55 to 53. That’s not a whole lot of change, and that’s why, since Netanyahu called early elections, it’s been almost certain that Netanyahu will remain prime minister (though it’s more unclear whether he’ll govern with a more rightist or centrist coalition).

Levy’s harsh conclusion is that Israel is coming to resemble apartheid-era South Africa.

But it looks to me even more like the highly choreographed confessional politics of its northern neighbor, Lebanon.

Israel’s demographic trends make it very likely that its population will become more polarized (like Lebanon’s) in the coming years — Israeli haredi and Israeli Arab populations are growing much faster than secular Jewish populations, such that the haredim and Arabs, taken together, will outnumber the rest of Israel’s population within the next 40 years. As such, the disintegration of two-party Israeli politics into de facto confessional politics in Israel is cause for worry. Continue reading The Lebanonization of Israeli politics and next week’s Knesset elections →

![]()