Since Coalition prime minister John Howard lost the 2007 election, and thereby leaving office after 11 consecutive years in office, Australia has changed prime ministers exactly four times.![]()

That wouldn’t be so remarkable in an era of rapid change and economic anxiety — except for the fact that Australians have only gone to the polls twice since 2007.

Internal coups, unknown in the democratic and developed world outside Japan, within both the center-left Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the center-right Liberal Party (the dominant partner in the ‘Coalition’ with the more socially conservative National Party) have made politics in Australia possibly more exciting in between elections than during election campaigns.

Prime minister Malcolm Turnbull came to power only last September after ousting his more conservative predecessor Tony Abbott in an internal coup, as Liberal MPs in Australia’s House of Representatives began worrying about polls that showed Abbott would easily lose the next election. Those polls turned around when Turnbull, a more moderate figure who led the Liberal Party briefly from 2008 to 2009 and who led the 1999 campaign to transform Australia from a constitutional monarchy into a republic, became prime minister.

Labor leader Bill Shorten, in his own right, has managed to do in opposition what Labor couldn’t manage when it was in government for six years — remain united. Though Labor was elected in 2007 with a wide mandate for Kevin Rudd, he was ousted by his own deputy prime minister, Julia Gillard, within two years. Though she won a narrower mandate in her own right in 2010, the Labor caucus, in turn, ousted Gillard in mid-2013 when it appeared that she would not win the next election. Instead, they turning back to Rudd, who subsequently lost the 2013 election, however narrowly, to Abbott and the Coalition.

As Australia goes to the polls in a campaign that has been unmercifully long by Australian standards and mercifully short by American standards (eight weeks), neither Turnbull nor Shorten seem to inspire much confidence from the electorate. The two have spent the campaign tussling over issues from health care to the economy to LGBT marriage equality to immigration and, in the process, making voters like each of them less.

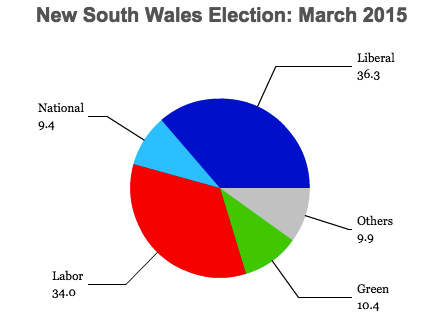

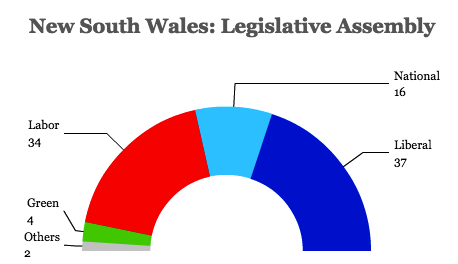

It’s a tight race. Polls show that the Coalition holds the narrowest of advantages, about 51% to 49%, over Labor in the so-called ‘two-party preferred’ vote — which reflects the outcome of a compulsory electoral system that features a preferential instant-runoff mechanism. It’s almost certain that the Coalition is doing far better than it would have been under Abbott’s leadership, though it’s almost just as certain that, even if Turnbull wins, it will be with a much reduced majority in both houses — and in each house, the balance of power may lie with third parties such as the Australian Greens.

Though both the center-right Turnbull and the center-left Shorten are sensible moderates well capable of governing Australia in a competent and centrist manner, voters seem to have tired of the internal scheming that have come to characterize both of the country’s two major parties.

Turnbull, once a moderate lion who championed climate change legislation, LGBT equality and an Australian republic, was forced by his more right-wing caucus to run on a platform around an AUS$48 billion corporate tax cut.

Shorten, who once vowed to defend the carbon trading scheme, is running on an ambiguous platform, shellshocked by the damage that Labor sustained in 2013 over what was perceived as a double mining tax and carbon tax. Those issues have become especially tender now that the Chinese economy has slowed and the global demand for commodities is somewhat subdued.

On gay marriage, both Turnbull and Shorten personally favor marriage equality. But Turnbull has been pushed towards supporting a nation-wide referendum on the matter, while Shorten has promised to call a vote in the Australian parliament if elected. The Labor position is that a plebiscite is a Coalition tactic to divide Australians that would bring unnecessary strife and animosity to the LGBT community (though Shorten in recent days has taken flak for once supporting such a vote).

Though the Great Barrier Reef is going through a horrific moment of coral bleaching, Australian politics is moving away from the carbon trading scheme (and mining tax) that Rudd promised, that Gillard enacted and that Abbott repealed. Ironically, Abbott ousted Turnbull from the Liberal leadership in 2009 after Turnbull tried to strike a deal with Rudd on the carbon trading scheme. Today, Turnbull, in thrall to his more conservative parliamentary caucus, would never sign up to a similar deal. Shorten, for his part, failed to stop the carbon trading scheme’s repeal last year.

In recent years, both parties have moved towards a more restrictive immigration policy. Both are now wedded to the policy of offshore detention of immigrants bound for Australia in subpar camps in Nauru and Papua New Guinea, notwithstanding a Papua New Guinean judicial ruling in April that called into constitutional question Australia’s immigration policy.

In some ways, the Australian election feels retro, like a British election a quarter-century ago. Australian commentators are still talking about ‘swings’ from the Coalition to Labor in a two-party world. That’s even as the Australian Greens stand to make even more gains in Saturday’s election, under the leadership of Richard Di Natale, a senator from Victoria, who took over the party’s leadership in May 2015. Nick Xenophon, an independent-minded senator from South Australia who came to power initially to oppose gambling machines in the late 1990s, is now leading a centrist ‘Nick Xenophon Team’ that could win seats in both houses.

The stakes are particularly higher in 2016, because Australia is having (for the first time since 1987) a so-called ‘double dissolution’ election, in which all 150 members of the parliament’s lower house, the House of Representatives, and all 76 members of the upper house, the Senate, are up for election. In most elections, only half of the Senate’s members are on the ballot — in other words, half of an Australian state’s 12 senators are up for election.

But the current Senate is deadlocked. While the Coalition has more seats than Labour (an advantage of 33 to 25), 10 members of the Senate belong to the Green Party and another eight senators belong to other small parties or sit as independents.

If Australia’s House of Representatives and Senate twice fail to agree on legislation, the government may prevail upon the governor-general to dissolve both the House and the Senate under section 57 of Australia’s constitution. In the current election, four bills qualify to trigger such a double-dissolution election.