If anyone had doubts, it’s clear now that Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has a clear grip on his country.![]()

When Modi swept to power in 2014 by capturing the biggest Indian parliamentary majority in three decades, he did so by unlocking key votes in Uttar Pradesh. Ultimately, Modi owed his 2014 majority to the state, which gave him and the Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) 73 of its 80 seats to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament.

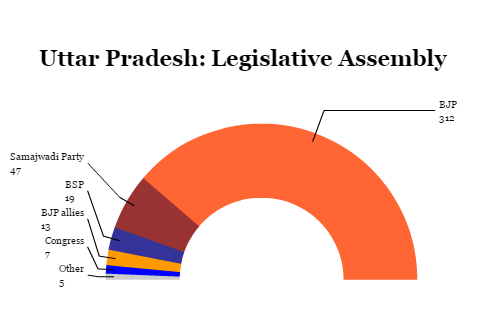

Nevertheless, it was a surprise last weekend — even to Modi’s own supporters — when, after seven phases of voting between February 11 and March 8, officials reported that the BJP won over three-fourths of the seats in the Uttar Pradesh legislative assembly. That’s a landslide, even in the context of a state where voters like to see-saw from one party to the next every five years. The BJP victory marked only the fourth time in history (and the first time since Indira Gandhi’s victory in 1980) that a single party won over 300 seats in the UP legislative assembly, and it bests the earlier BJP record (221 seats in 1991) by just over 90 seats.

A referendum on demonitisation

The victory in Uttar Pradesh, one of five state elections for which results were announced on March 11, amounts to a massive endorsement of Modi (less so of the BJP). Though the 2019 elections are over two years away, the victory will give Modi some comfort that he will win reelection. For now at least, the Uttar Pradesh victory shows just how far behind Modi the opposition forces have fallen.

With over 200 million people, Uttar Pradesh is the most populous state in the country and, indeed, it’s home to more people than all but five countries worldwide.

In some ways, Modi’s staggering victory in Uttar Pradesh this spring is even more spectacular than his 2014 breakthrough. After all, Modi was defending a three-year record as prime minister that hasn’t been perfect. Despite winning the biggest parliamentary majority since 1984, the protectionist wing of the BJP has slowed the pace of Modi’s economic reforms. It was only last November that Modi successfully completed a years-long push to reform the goods and sales tax — a landmark effort to harmonize state levies into a single national sales tax, thereby lowering the costs of doing business between Indian states. Those obstacles still exist, as evidenced by the truckers lined up at state borders for hours or days on end.

For all the supposed benefits of the November 2016 demonetisation plan, its rollout was cumbersome, with the sudden removal of 500-rupee and 1,000-rupee bills from circulation in a country where 90% of all transactions are cash transactions, most of which involved the two ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes (equivalent, respectively, to $7.50 and $15.00 in the United States). Though Modi hoped the abrupt step would stem corruption and retard the flow of illicit ‘black money’ that’s evaded taxation, the move also inconvenienced everyday commerce and trade, as ordinary and poor Indians struggled to transition to the new system.

So the state elections — in Uttar Pradesh as well as Uttarakhand, Punjab, Manipur and Goa — were referenda on Modi’s reform push, in general, and demonetisation, in particular.

Modi passed the test, as voters gave his government the benefit of the doubt — and he did it on his own, with the help of his electoral guru, Amit Shah, a longtime aide to Modi during Modi’s years as chief minister in Gujarat and the engineer of the BJP’s victory in Uttar Pradesh in 2014 and, since 2014, the BJP party president.

So personalized was Modi’s campaign that the BJP didn’t even bother naming a candidate for chief minister. So the BJP won a three-fourths majority in India’s largest state without ever telling voters who it intended to serve as the state’s top executive. Speculation initially revolved around Rajnath Singh, the 65-year-old home secretary who once served as chief minister of Uttar Pradesh from 2000 to 2002 and who is himself a former BJP president. But But 57-year-old communications and railways minister Manoj Sinha, who was born in Ghazipur and represents the city in the Lok Sabha, is also a leading contender. Modi and Shah are expected to make a decision by Saturday.

Uttar Pradesh is state that could use some reforms. Its large Muslim population in what’s traditionally considered the Hindu heartland has led to more than its fair share of communal violence over the years, and the state remains less developed than India as a whole.

Modi benefited from divided opposition

It’s also a state governed by two regional parties since 2002, when the last BJP state government fell, forcing the state into ‘president’s rule’ until a fresh election could be held.

The first beneficiary was Mulayam Singh Yadav, who founded the Samajwadi Party (SP, समाजवादी पार्टी) as a socialist regional alternative to the leading national parties in 1992 and who won a plurality of the seats in the 2002 election.

The second beneficiary was Mayawati, the charismatic Dalit who regained power in a 2007 landslide as the head of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP, बहुजन समाज पार्टी). which consolidated the votes of Muslims and lower castes to form a lower-class majority in the state.

In 2012, power swung back to the Samajwadi Party, however, under the leadership of Mulayam’s son, Akhilesh Yadav, uniting certain “other backward class” castes, including the Yadav caste.

By 2017, however, the Samajwadi Party found itself trapped in a self-defeating internal crisis that pitted its founder against his own son. The party (and the son) entered, at the father’s opposition, an ill-fated alliance with the Indian National Congress (Congress, or भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस), the nominally center-left, secular party so dominant in Indian politics since independence that failed miserably in 2014 under the leadership of Nehru-Gandhi family scion Rahul Gandhi. Meanwhile, Mayawati’s appeal flagged after years of corruption allegations and her unwillingness to join forces with the SP and Congress in a united anti-Modi front. Muslims failed to unite behind the BSP, instead splintering off to both the SP and Congress, leading Hindus to eye all three parties with greater suspicion. Among the most important keys to Modi’s victory was caste — uniting almost all the non-Yadav OBC castes behind the BJP.

Congress continues to flounder with no compelling alternative to Modi and an even less compelling leader in Rahul Gandhi, whose sole qualification for the role is his family pedigree. Despite waves of electoral defeats and mounting evidence (even before 1014) that Indians simply do not like him, Rahul has managed to keep the party leadership. At this rate, Congress is in danger of even deeper losses than in 2014, when its once-considerable strength collapsed to just 44 seats in the Lok Sabha, not enough to form the official opposition.

All of which allowed Modi’s BJP to divide and conquer its opponents, giving it the supermajority that almost no one expected.

Congress holds on in Punjab

Modi’s BJP also easily won power in the northern Himalayan state of Uttarakhand. Trivendra Singh Rawat, the state BJP president, will serve as chief minister, returning the state’s government to BJP rule for the first time since 2012. Since the state’s inception in 2000, the BJP and Congress have essentially traded power at every election.

In Manipur (2.7 million people) and Goa (1.5 million people), two smaller jurisdictions, Congress still managed to win more seats than the BJP, though the BJP quickly found enough local allies to enter government anyway.

But in the Sikh-majority state of Punjab, the second-largest prize of the five state elections (with 27 million people), Congress made its only true gain of the spring, taking power after a decade in opposition.

In a three-way race among the Congress, the Sikh-interest Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD, ਸ਼੍ਰੋਮਣੀ ਅਕਾਲੀ ਦਲ) and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी पार्टी, ‘Common Man’s Party), the Congress won 38.5% to just 25.2% for the SAD and a disappointing 23.7% for the AAP.

The BJP, as a junior partner to the SAD-led government in Punjab for the last 10 years, won only around 5.4% of the vote.

Amarinder Singh, an old-school Congress official, who served as chief minister of Punjab when Congress last controlled the legislative assembly from 2002 to 2007, will now return as chief minister. If, as expected, Congress loses elections next year in Karnataka, Singh will be the most important chief minister left standing in India.

The AAP’s failure to break through will come as a disappointing setback for its leader, Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal. Though an AAP government controls the Delhi government, Kejriwal still has hopes of making his good-government, anti-corruption party the national opposition to Modi, and Punjab was one of the places where observers believed voters would be receptive to Kejriwal’s approach — and weary of a decade of uninterrupted SAD rule.

Modi’s mixed record in state elections

Though the Uttar Pradesh victory is a sweet triumph for Modi, the BJP hasn’t had sweeping luck in its state elections since his initial 2014 breakthrough. Glowing in its 2014 honeymoon, the BJP easily won power in Maharashtra in the southwest (home to Mumbai) and Haryana in the northwest.

Elections in 2015, however, weren’t so kind. In February, the AAP easily won power in the national capital territory of Delhi. Later in November, in Bihar, Nitish Kumar mounted a comeback, winning a third consecutive term and powerfully reducing the BJP’s footprint.

In May 2016, three regional giants blocked the BJP from making gains into new terrain. In the far southeastern Tamil Nadu, where the BJP hasn’t historically been a major political force, the beloved actress-turned-populist leader, chief minister Jayalalithaa, having just beaten another corruption rap, easily won state elections (though she died last December).

In the far-eastern and impoverished West Bengal, the BJP won just six seats as Mamata Banerjee’s local movement easily retained power. That’s despite a final agreement negotiated by Modi’s government to settle Indian and Bangladeshi enclaves on either side of the border.

Likewise, in Kerala, in the southwest, the Communist Party of India defeated an incumbent Congress government.

The one bright spot in 2016 was Assam, a state with one of the highest proportions of Muslims (over 34%), where the BJP took 55 seats and a near-majority in June, governing with two local parties.

Between now and the next general election, Modi faces elections later this year in his home state of Gujarat and the far northern Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh, as well as the indirect election of India’s president. In 2018, among the eight states voting, the BJP will attempt to retake the state of Karnataka (home to Bangalore and the southern information technology corridor), and retain its majorities in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

These c1xasezf.gq http://c1xasezf.gq/ are costly however, they appear good and they are made of a superb top quality. I enjoyed them so a lot that I did not put them away.