For the better part of a week, exit polls showed that Tamil Nadu’s chief minister Jayalalithaa, both beloved and scandal-plagued, was in trouble of being rejected by voters. ![]()

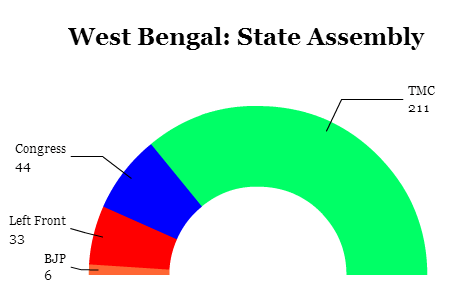

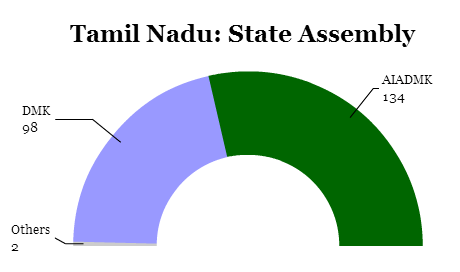

But when election officials announced the results Thursday for the May 16 state elections, her governing AIADMK (All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam) instead won a resounding victory. It proved the staying power of one of India’s most enchanting regional leaders, despite her temporary, nine-month suspension as chief minister that followed a 2014 a conviction on corruption charges, and despite disastrous flooding late in 2015 that affected the Tamil capital of Chennai and that killed over 400 people throughout the state.

None of those problems seemed to matter to Tamil voters, who returned the AIADMK to power, five years after Jayalalithaa returned to power at the state level and two years after she nearly routed both regional and national parties in India’s parliamentary elections.

Despite the pollsters’ last-minute spook in Tamil Nadu, none of the results announced Thursday in spring elections across five states offered much of a surprise. But the voting, across five states, from India’s northern border with China down to its most southern tip, which incorporated, in aggregate, a population of over 225 million Indians, was as close to a ‘midterm’ vote as prime minister Narendra Modi will get.

Regional parties are stronger than ever

In the spring’s two biggest prizes — West Bengal and Tamil Nadu — voters delivered resounding victories to regional leaders like Jayalalithaa and West Bengal’s chief minister Mamata Banerjee.

* * * * *

RELATED: Banerjee eyes reelection in West Bengal state election results

* * * * *

The resilience of regional parties, often more tied to personality or class patronage than to a set of policies or rigid ideology, shouldn’t have been a surprise. Following the spring voting, 15 Indian states are now governed by chief ministers from regional or left-wing third parties. Last year, Modi’s governing Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) suffered humiliating setbacks both in Delhi and in Bihar, the former to clean-government guru Arvind Kejriwal in the latter to a regional party alliance headed by chief minister Nitish Kumar, one of a handful of politicians in the country with a better record on economic growth and development than Modi himself.

The intricate role of caste, class and religion is at work in many of India’s states, and that has increasingly made it difficult for either the BJP or its more secular centrist rival, the Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस), to maintain dominance. As a populist alternative, regional parties have succeeded on a state-by-state level where other ‘third front’ efforts have failed at India’s national level.

Politics in the far southwestern Tamil Nadu, India’s sixth-most populous state with over 72 million people, is typically a battle between regional ‘Dravidian’ Tamil parties.

Politics in the far southwestern Tamil Nadu, India’s sixth-most populous state with over 72 million people, is typically a battle between regional ‘Dravidian’ Tamil parties.

Jayalalithaa’s AIADMK typically seesaws in power with the DMK (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, திராவிட முன்னேற்றக் கழகம், Dravidian Progress Federation). Her chief rival is the 91-year-old Karunanidhi, who was first elected as chief minister in 1969 and, like Jayalalithaa and many of the state’s leading political lights, began his career in the Tamil film industry.

It’s no understatement to say that Tamil politics, blurring the line between big-screen and governance grandeur, is dramatic, with the chief minister’s supporters weeping, worshipping and sometimes, violently self-immolating in her honor. Her victory in Tamil Nadu, a state with relatively strong governing institutions, assures at least five more years of rule and, perhaps, five more years of handouts, from drinking water to laptops, all of which are branded with the smiling face of ‘Amma’ (the Tamil word for mother), as Jayalalithaa is affectionately known by supporters.

It also means that Karunanidhi will probably not make another run as chief minister, though his able son, the 63-year-old Muthuvel Karunanidhi Stalin, a former deputy chief minister and former Chennai mayor, seems destined to become a future state leader, and he dominated headlines by waging a stronger-than-expected DMK campaign in 2016.

Banerjee, who won reelection in West Bengal, broke away from the Congress Party in the late 1990s to form her own Bengali party, the All India Trinamool Congress (AITMC, সর্বভারতীয় তৃণমূল কংগ্রেস). For nearly two decades an effective opposition leader, Banerjee in 2011 swept out of power a communist government that had ruled the state continuously for 34 years.

Since 2011, Banerjee and the AITMC have failed to live up to the heady expectations of change, and her government was embarrassed by a local new organization’s sting operation of top party officials allegedly agreeing to take bribes for public services. Nevertheless, she has introduced popular policies that have appealed to the rural poor of West Bengal, in particular, subsidized rice prices and cash prizes to families with girls who complete secondary education. She’s managed to introduce at least some fiscal discipline in India’s fourth-most populous state (over 92 million people) — and not one that’s especially known for its smooth government, though its capital Kolkata once served as the capital of the British empire in India. The province is just one part of a larger Bengali-speaking region that also includes the country of Bangladesh, and border issues between the two have dominated headlines in the past year as officials have agreed on land swaps of Indian and Bangladeshi enclaves on either side of a porous border.

As in Tamil Nadu, voters (including Muslims who make up around 27% of the population) overlooked the graft and the inefficacy of Banerjee’s first term, rebuffing an electoral alliance between the state’s Left Front coalition and the Congress.

Congress is still very unpopular across India

Pity poor Rahul Gandhi.

After Congress fared so poorly in the 2014 elections that it fell below the threshold number of MPs to form an official opposition in India’s parliament, it suffered loss after loss to the BJP at the state level, including in powerful Maharashtra, home to Mumbai. When the BJP suffered losses in 2015, it wasn’t to Congress, but to regional powers that had previously vanquished corrupt Congress governments, like Kejriwal’s anti-corruption Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी की पार्टी, Common Man Party).

For Congress, which has governed India far longer than any other party in post-independence history and is, to a dwindling number of older voters, still the party of Indian independence, dominated by the Nehru-Gandhi family, the 2016 spring elections represent an even deeper crisis of relevance. Today, Congress holds power in just seven states — and in just two of the 20 most populous.

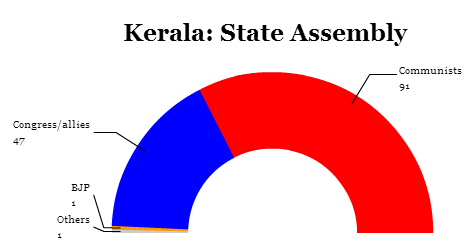

In Kerala, for example, a Congress-led government fared poorly against the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPM, भारत की कम्युनिस्ट पार्टी (मार्क्सवादी)), which easily rode back to power in a state that’s long been favorable to far-left politics.

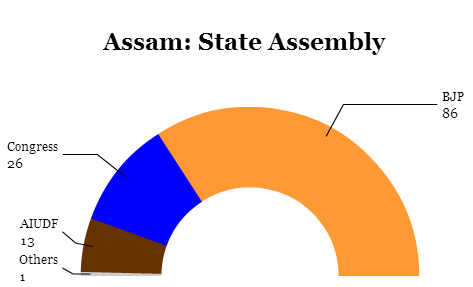

No matter whether the Congress was running to the left (allied with West Bengal’s communists) or to the right (against Kerala’s communists) or as the secular alternative to the BJP (as in Assam), it seems that even fewer voters are finding the message of Rahul Gandhi, the family’s latest scion and Congress’s leader, compelling. Far from learning the lessons of the 2014 election, Congress has doubled down in relying on the Gandhi family name. Rahul Gandhi himself comes across as a blue jeans-clad, out-of-touch foreigner in his own home country. He never served under the decade-long government led formally by prime minister Manmohan Singh and, informally, by his mother, the Italian-born Sonia Gandhi. But more damaging, Rahul Gandhi has no response to the party’s incredible record of corruption while in power, and he has developed no credible rationale for voters to reject Modi, even as BJP leaders increasingly rail against ‘anti-national’ elements of student protests and other anti-Modi movements.

The BJP is by far the dominant national party of India

For Modi and his chief strategist Amit Shah, the spring elections didn’t have to be a five-state sweep.

It was simply enough that the BJP won such a strong victory in the Himalayan state of Assam. It’s so impressive because the BJP has never wrested control of the state from local parties or from Congress. In part, that’s because the BJP’s brand of Hindutva nationalism traditionally alienated Muslims, and over 33% of Assam’s population are practicing Muslims. Learning from the bitter lessons of past failures, the BJP promoted from the beginning of the campaign a charismatic chief ministerial candidate in Sarbananda Sonowal, a former member of the Assam legislative assembly and since 2014, Modi’s minister for youth affairs and sports. (Believe it or not, parties in India do not universally announce a chief minister candidate in state-level elections.)

After its 2015 setbacks in Delhi and Bihar, the Assam victory gives Modi some breathing room, electorally speaking, at least until the all-important Uttar Pradesh elections next year, 2018 elections in Karnataka (home to Bangalore and the center of India’s information technology industry) and the battle for reelection in elections that must take place before 2019.

Though it doesn’t seem like much, it was also something of a breakthrough that the BJP won even a handful of seats in states where it had virtually no presence a decade ago — one in Kerala, six in West Bengal. That will give Modi and Shah some hope that it can expand the BJP’s potential in 2019.

Most of all, however, the BJP’s 2016 successes have upended the narrative that Modi has lost his magic touch with the Indian electorate. It gives him an opportunity to turn back to the more difficult task of reforming India’s sputtering economy, most notably through the passage of a universal goods and services tax that will replace state levies that have hindered trade between India’s states. As it turns out, even a ‘Modi wave’ in 2014, a mandate for reform and development, didn’t magically transform the BJP from instincts that are as protectionist as any of India’s other national or regional parties. The road ahead for Modi will be difficult. As his predecessor Manmohan Singh learned, a reform-minded prime minister alone cannot liberalize India’s economy.