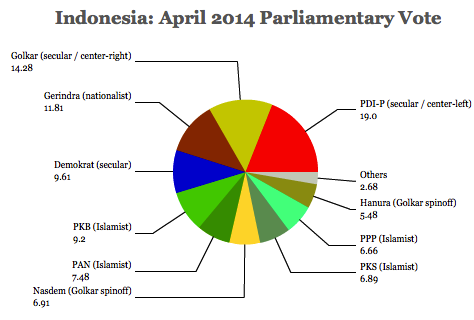

Given that Indonesia is the world’s fourth-most populous country, the 15th largest world economy (and likely to grow), the second-most populous democracy and the most populous Muslim democracy, its elections this spring and summer are nearly as important as those in the European Union and in India.

Democracy came to Indonesia only gradually. After the fall of Indonesia’s president Suharto in 1998, the country held its first democratic parliamentary elections in 1999 and its first direct presidential election in 2004.

In 2004, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono became Indonesia’s first directly elected president. When he steps down later this year, he’ll leave behind a country firmly on a democratic track and with one of the world’s strongest emerging economies. Indonesia’s GDP skyrocketed during his administration from $256.8 billion in 2004 to $878 billion in 2012 — and growing. Between 2004 and 2012, Indonesia had an average GDP growth rate of 5.78%.

That doesn’t mean that there isn’t room for improvement on any mix of economic, social or political measures. Indonesia’s next president will face several challenges. Its infrastructure — roads, train networks and ports — falls far behind that of China or even India. It has a growing urban population that suffers from flooding, pollution, clogged traffic, poor housing conditions and inferior health care and education services. Indonesia’s next president must also design an economic policy that will bring productive growth to Indonesia without chasing away foreign investment. With the East Timor and Aceh questions settled, Indonesia’s next president won’t face any pressing existential issues of national identity, notwithstanding ongoing pressure from Islamists.

But after a decade of ‘normal’ politics, July’s election will be more conventional than historical.

For over a year, the frontrunner in the presidential race has been the governor of Jakarta state, Joko Widodo (known simply as ‘Jokowi’ to most Indonesians). The new star of Indonesian politics, Jokowi (pictured above) has been compared to US president Barack Obama for his meteoric rise, though he only entered the presidential race last week. He rose to national prominence only after winning the September 2012 Jakarta gubernatorial election, ousting the one-term incumbent, Fauzi Bowo, of Yudhoyono’s governing Partai Demokrat (Democratic Party).

In the past two elections, his party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P, Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan) nominated Megawati Sukarnoputri as its presidential candidate. The daughter of Sukarno, Indonesia’s first post-independence leader who governed Indonesia between 1947 and 1964, Megawati served as president between 2001 and 2004. Megawati’s apparent decision to pass the leadership baton to Jokowi is a sign that, at age 67, Megawati has begrudgingly determined that a presidential comeback isn’t likely.

Jokowi comes from a younger generation that came of age not under Sukarno, but under Suharto, a more authoritarian figure who pulled the country away from socialism and towards economic liberalism, as well as away from the Soviet Union and China and toward the United States.

Jokowi made the leap from business — he once sold furniture — to politics only within the past decade. As mayor of Surakarta (Solo) between 2005 and 2012, and as governor of Jakarta today, Jokowi has become known for a hands-on political style, which involves the tradition of blusukan — impromptu visits throughout his city to check in with everyday Indonesians, a touch that allows Jokowi to connect with Indonesian voters better than other members of the political elite, including Yudhoyono. That approach has made Jokowi incredibly popular, and it has given him the kind of profile that Cory Booker recently enjoyed as mayor of Newark, New Jersey — a responsive super-official ready to deal with emergencies from flooding to traffic at a moment’s notice, though those problems remain endemic to Indonesia’s chaotic capital. As Jakarta’s governor, he’s increased spending on education programs, and he’s raised the minimum wage twice (first by 44% and by 9% in 2013).

Perhaps the most comprehensive policy that Jokowi has implemented in Jakarta is a universal heath care program quickly introduced upon taking office in 2012. Like the health care reforms introduced by Obama, Jokowi was criticized for the program’s rollout and implementation, which included a surge in demand for medical services.

But that doesn’t necessarily explain what he would do as Indonesia’s next president. Continue reading Who is Joko Widodo? →

![]()