With over 180 million citizens, only five countries in the world have a larger population than Pakistan.

Divided in 1947’s Partition from India when both countries received independence from the United Kingdom, and separated from ‘East Pakistan’ — today’s Bangladesh — after a bloody 1971 war, Pakistan sits at the heart of South Asia as a key to not only regional, but also global security.

That makes it one of the most important of 2013’s world elections.

The country shares a border along its southwest with Iran, a country under sanction from the European Union, the United States and others and a potential geopolitical hotspot over its nuclear weapons program. The country shares a long, mountainous border with Afghanistan, where U.S. troops have been engaged in military operations to keep the Taliban at bay since October 2001, though troops are set to leave later this year and its president, Hamid Karzai, is expected to step down after next spring’s presidential election. Of course, Pakistan shares its eastern border with India, and its northeastern border with the contentious province of Jammu and Kashmir that have soured Indian-Pakistani relations for years, and which has taken on global security significance since the late 1990s when first India, then Pakistan, became nuclear-armed powers.

Where India remained closer to the Soviet Union during the Cold War, Pakistan was always a U.S. ally, a role that’s continued throughout the post-Cold War era. That’s been especially true since the 2001 terrorist attacks — U.S. military action in Afghanistan has so routinely involved close coordination with Pakistani military advisers that U.S. security experts now casually speak of the ‘Af-Pak’ security theater, and Pakistan has been a lethally familiar target of U.S. drone strikes. In 2010, al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden was discovered and killed not in his home country of Saudi Arabia or in nearby Afghanistan, but in a compound in Abbottabad, in Pakistan.

It’s a country that’s struggled to find a balance between too-often corrupt civilian leadership and overeager military leadership, and its recent political history is marked by seesawing between military coup leaders and democratically elected politicians. The current government of Pakistan, however corrupt and/or unpopular, is only the first government in Pakistan’s post-independence history to serve a full five-year mandate. Most recently, general Pervez Musharraf, the army chief of staff, took military power in 1999 and governed until 2008 as a steadfast ally of U.S. president George W. Bush.

In advance of elections in February 2008, two former prime ministers in exile, Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif, returned to Pakistan to campaign for office.

Bhutto, the leader of the center-left, urban-based Pakistan People’s Party (PPP, پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی), was the daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a Pakistani prime minister in the 1970s who was controversially executed in 1979 by a military-led government. Bhutto had served as prime minister twice — from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 to 1996, before spending much of the next decade in exile during the Musharraf era. Bhutto was tragically assassinated in December 2007, however, which, in part, led to her party’s victory in the 2008 elections.

Sharif, the leader of the center-right, rural-based Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML-N, اکستان مسلم لیگ ن), served as prime minister from 1990 to 1993 and again from 1997 to 1999. Sharif, in fact, had appointed Musharraf as his army chief of staff, only to be overthrown in due course by Musharraf.

Despite the return of civilian government five years ago, the Pakistani army and the Inter-Services Intelligence wield massive power within Pakistan, essentially dictating security and foreign policy, while retaining a key role in domestic matters and not insignificant influence in the Pakistani economy as well. The current army chief of staff, Ashfaq Kayani, has largely remained aloof from directly engaging political discourse, though his term ends in November 2013 — meaning that the new government will be responsible for choosing his successor.

So what’s at stake in the May 11 elections?

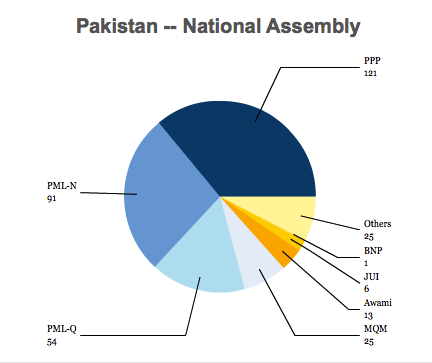

The election will determine the composition of the National Assembly (ایوان زیریں پاکستان), the lower house of the Majlis-e-Shura ( مجلس شوریٰ), Pakistan’s parliament. Although the National Assembly has 342 members, 70 of the seats are set aside for women and religious minorities, so only 272 members will be elected directly — as you might guess, that makes it even more difficult for any single party to win a majority of the National Assembly. Each member is elected to a five-year term on a first-past-the-post basis in single-member constituencies (though the National Assembly can be dissolved earlier with the consent of the president and prime minister).

The election will also determine the membership of each of the provincial assemblies in Pakistan’s four major provinces:

- Punjab, which comprises 54% of Pakistan’s population, is the strategic Pakistani heartland. Its residents, who are over 97% Muslim, predominantly speak Punjabi. It’s home to though it features to the country’s capital Islamabad and Lahore, a city of key historical importance to Pakistan.

- Sindh, home to 22% of Pakistan’s population and more cosmopolitan, given the presence of Pakistan’s largest city and its coastal financial hub, Karachi. A majority of the population speaks Sindhi, and while the province is over 90% Muslim, there’s a small Hindu minority.

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, home to 13% of the population, crawls across Pakistan’s northwest, and is predominantly Pashtun, with Pashto the major language. The area includes between 1 and 2 million Afghan refugees, though the province excludes much of the actual border with Afghanistan, which is separately administered as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA).

- Balochistan, home to just 5% of the population, is a relatively spare expanse that includes a number of different groups — a bare majority of its residents speak Balochi, and just over a quarter speak Pashto, with small amounts of Sindhi and Punjabi speakers.

So who are the major parties and figures contesting the national elections?

PPP. Although Bhutto’s widower, Asif Ali Zardari, became Pakistan’s president in September 2008, his popularity has waned following multiple allegations of corruption, and he nearly found himself impeached and removed from office. As a result, he largely transferred many of the powers of the Pakistani presidency, as an institutional matter, to the prime minister. The government’s first prime minister, Yousuf Raza Gillani, served until June 2012, when he was removed by Pakistan’s supreme court, retroactively disqualified as prime minister due to his refusal to facilitate a graft case against Zardari. His successor, Raja Pervaiz Ashraf, a former water minister, led the government as prime minister through the end of the government’s natural term in March 2013. The PPP-led government of the past five years remains relatively unpopular with voters on nearly every basis — unemployment, inflation and poverty are high, GDP growth is low, and many citizens in Pakistan lack basic access to water, electricity, health care and education. Bilawal Zardari Bhutto, the son of Zardari and Benazir Bhutto, remains the co-leader of the party along with his father, though at age 24, he’s too young to contest the 2013 elections.

PML-N. Sharif’s party is widely expected to return to power and Sharif himself is expected to become Pakistan’s next prime minister, largely on the strength of his party’s rural base in Punjab province, where polls show that the PML-N is far and away the favorite to win many of the seats in Pakistan’s largest province. Shahbaz Sharif, his brother, has served as chief minister of Punjab province since 2008, and is also widely favored to win reelection. Sharif has pledged that if elected, he’ll appoint the highest ranking official to succeed Kayani as army chief of staff in order to make the decision as apolitical as possible. He’s also waged a campaign largely targeted at economic reforms.

PTI. Former cricket star Imran Khan founded the secular, anti-corruption, liberal Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Movement for Justice or PTI, پاکستان تحريک) in 1996, though this year looks to be his breakout year. Though polls aren’t exactly reliable, the PTI may well win more seats than the PPP, with voters disenchanted by both the Bhutto-controlled PPP and its corruption and the PLM-N. Khan’s stridently nationalist stance against U.S. drone strikes has made for some extremely odd bedfellows, and some of the most radical, violent elements in Pakistani public life have, if not exactly endorsed Khan, shared common cause with him. Nearly alone among parties, the Tehrek-e-Taliban Pakistan (commonly known as the Pakistani Taliban) has made it clear that, despite a violent campaign against most civilian parties, it will not attack Khan and PTI events.

MQM. The more liberal, urban-based Muttahida Quami Movement (متحدہ قومی موومنٹ) is an almost entirely Karachi-based party with a potent, urban political machine that’s long made it the dominant force in local Karachi politics. Nationally, it has typically aligned itself in PPP-led coalitions.

PML-Q. During the Musharraf era, a small band of PML-N centrists broke off to form their own cohort in support of Musharraf, the Pakistan Muslim League (Q) (پاکستان مسلم لیگ ق, or the PML-Q). Though it has now abandoned Musharraf and it is running as a coalition partner of the PPP, it’s set to be virtually wiped out.

Musharraf. Hoping to return to Pakistani politics, Musharraf returned earlier this spring from ‘self-imposed exile’ to lead a movement he formed in 2010, the All Pakistan Muslim League (APML, آل پاکستان مسلم لیگ). Immediately after returning to the country, however, Musharraf has encountered nothing but trouble. He is now under house arrest and faces serious charges that stem from his time in power, including treason over dismissing Pakistan’s supreme court in 2007 and charges that he failed to provide sufficient protection against Bhutto’s assassination in 2007 as well. Though his popular support was already negligible, he’s been barred from running in the elections and one court has issued a ruling barring him from Pakistani politics for life. His continued presence remains a significant difficulty for the Pakistani military, who don’t want to interfere with Pakistan’s judiciary, but also don’t want a precedent that could open additional military leaders to civil or criminal charges. How to handle Musharraf will be one of the more delicate challenges for Pakistan’s next government.

Local parties. Aside from the Karachi-based MQM, several local parties are worth noting. The Awami National Party (ANP, عوامی نيشنل پارٹی in Urdu, ملي عوامي ګوند in Pashto) plays a significant role in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as the largest Pashtun party in the country. Like the MQM and other smaller parties, it is also part of the PPP-led governing coalition, and it’s extremely anti-Taliban, pro-U.S. and widely supports the Karzai government in neighboring Afghanistan, stances that have made its leaders and members frequent targets of attacks by Taliban sympathizers. The Balochistan National Party (بلوچستان نيشنل پارٹی) is perhaps the most muscular party in Balochistan — it’s not based on ethnic identity like the ANP, but is a regionalist party based on the principle of greater autonomy and local control in Balochistan. Pakistan has an Islamist party, the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (جمیعت علمائے اسلام) but its religious conservative bent attracts surprisingly few supporters.

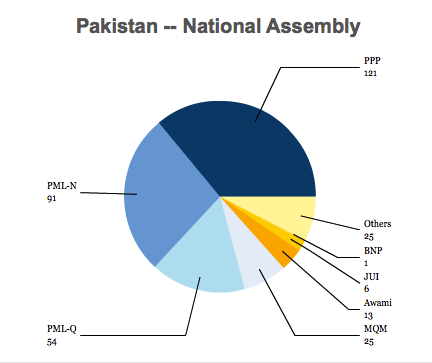

The current breakdown of the National Assembly is as follows:

Here’s all of Suffragio‘s coverage of politics in Pakistan:

Pakistan’s new president: Who is Mamnoon Hussain?

July 30, 2013

How the U.S. drone strike on the Pakistani Taliban undermines Sharif’s government

May 31, 2013

In one year, South Asia and the Af-Pak theater as we know it will be transformed

May 28, 2013

Can Nawaz Sharif and Ishaq Dar fix Pakistan’s sclerotic economy?

May 22, 2013

The foreboding political geography of Pakistan’s general election results

May 14, 2013

Six reasons why everyone in the United States should know who Nawaz Sharif is

May 13, 2013

Ten questions for Pakistan’s May 11 general election

May 10, 2013

Amid the PPP’s leadership crisis, where is Bilawal Zardari Bhutto?

May 9, 2013

Despite his tumble, Imran Khan is the key to Saturday’s Pakistani election

May 9, 2013

How does Pakistan hold a normal election campaign in the middle of widespread terrorism?

May 9, 2013

Musharraf didn’t need the Peshawar High Court to render him politically irrelevant

May 5, 2013

More about Pakistan’s ‘milestone’ and a preview of its upcoming May 11 elections

March 20, 2013

U.S. Justice Department memo justifies targeted killings of U.S. citizens abroad

February 5, 2013

Khan ‘peace rally’ near Waziristan border has implications for politics in Pakistan and beyond

October 8, 2012

Everything you need to know about the showdown between the Pakistani People’s Party and the Supreme Court of Pakistan

August 15, 2012

![]()