Last week, even before all of the votes had been counted, when it was clear that Nawaz Sharif would be Pakistan’s next prime minister, he named his designee for finance minister — Ishaq Dar (pictured above).![]()

Dar served as Sharif’s finance minister from 1998 until Sharif’s overthrow by army chief of staff Pervez Musharraf, and he spent much of his previous time as finance minister negotiating a loan package from the International Monetary Fund and dealing with the repercussions of economic sanctions imposed by the administration of U.S. president Bill Clinton on both India and Pakistan in retaliation for developing their nuclear arms programs.

Currently a member of Pakistan’s senate, Dar briefly joined a unity government as finance minister in 2008, though Dar and other Sharif allies quickly resigned over a constitutional dispute over Pakistan’s judiciary. The key point is that even across political boundaries, Dar is recognized as one of the most capable economics officials in Pakistan.

It was enough to send the Karachi Stock Exchange to a new high, and the KSE has continued to climb in subsequent days, marking a steady rally from around 13,360 last June to nearly 21,460 today. Investors are generally happy with the election result for three reasons:

- First, it marks a change from the incumbent Pakistan People’s Party (PPP, پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی), a party that has essentially drifted aimlessly in government for much of the past five years mired in fights with Pakistan’s supreme court and corruption scandals that affect Pakistan’s president Asif Ali Zardari in lieu of a concerted effort to improve Pakistan’s economy.

- Second, the election results will allow for a strong government dominated by Sharif’s party, the Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML-N, اکستان مسلم لیگ ن) instead of a weak and unstable coalition government.

- Finally, Sharif’s party is viewed as pro-business and Sharif himself, more than any other party leader during the campaign, emphasized that fixing the economy would be his top priority. Sharif, who served as prime minister from 1990 to 1993 and again from 1997 to 1999, is already well-known for his attempts to reform Pakistan’s economy in his first term.

Sharif will need as much goodwill as he can, because the grim reality is that Pakistan is in trouble — and more than just its crumbling train infrastructure (though if you haven’t read it, Declan Walsh’s tour de force in The New York Times last weekend is a must-read journey by train through Pakistan and its economic woes). The past four years have marked sluggish GDP growth — between 3.0% and 3.7% — that’s hardly consistent with an expanding developing economy. In contrast, Pakistani officials estimate that the economy needs more like sustained 7% growth in order to deliver the kind of rise in living standards or a reduction in poverty or unemployment that could transform Pakistan into a higher-income nation. Already this year, Pakistan’s growth forecast has been cut from 4.2% to 3.5%.

The official unemployment rate is around 6%, but it’s clearly a much bigger problem, especially among youth — Pakistan’s median age is about 21 years old. That makes its population younger than the United States (median age of 37), the People’s Republic of China (35) or even Egypt (24), where restive youth propelled the 2011 demonstrations in Tahrir Square.

Although Pakistan’s poverty rates are lower than those in India and Bangladesh, they’re nothing to brag about — as of 2008, according to the World Bank, about 21% of Pakistan’s 176 million people lived on less than $1.25 per day, and fully 60% lived on less than $2 per day.

Though it has dropped considerably from its double-digit levels of the past few years (see below), inflation remains in excess of 5%, thereby wiping out much of the gains of the country’s anemic growth:

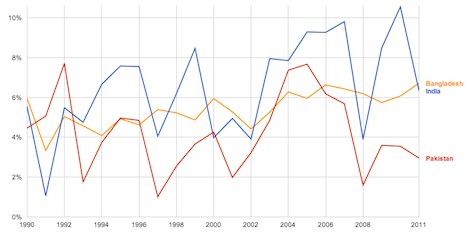

Pakistan is undeniably the ‘sick man’ of south Asia. India, even facing its own slump, has long since outpaced Pakistan over the past 20 years, and increasingly over the past decade, Bangladesh has consistently notched higher growth:

To make matters worse, Pakistan has a growing fiscal problem — although its public debt is lower than it used to be, it’s still over 60% of GDP, and a number of problems have led to debt-financed budgets in the past, including a 6.6% deficit in 2012.

That sets up a classic austerity-vs-growth conundrum for the Sharif government.

On the one hand, the familiar austerity hawks will argue that Sharif should focus on a reform program to lower Pakistan’s unsustainable deficits as a top priority. If, as expected, Sharif obtains a deal with the IMF for up to $5 million in additional financing to prevent a debt crisis later in 2013, the IMF could force Pakistan into a more aggressive debt reduction program than Sharif might otherwise prefer.

On the other hand, given the number of problems Pakistan faces, growth advocates will argue that Pakistan should focus on more pressing priorities and save budget-cutting for later. After all, with rolling blackouts plaguing the country, no one will invest in Pakistan regardless of the size of its debt. It’s also important to remember that Pakistan is not Europe — it’s an emerging economy with a young and growing population that could easily grow its way out of its debt problems in a way that seems impossible for a country like Italy or Greece.

So how exactly will Sharif and Dar attempt to fix Pakistan’s economy? Here are eight policies that Sharif’s government is either likely to implement — or should be implementing: Continue reading Can Nawaz Sharif and Ishaq Dar fix Pakistan’s sclerotic economy?