Photo credit to Diario de Navarra.

Photo credit to Diario de Navarra.

If you thought that the Scottish independence referendum was a divisive matter, just wait another three weeks.![]()

![]()

Even though Catalunya’s regional president Artur Mas officially cancelled a scheduled referendum on Catalan independence originally scheduled for November 9, diffusing a constitutional crisis with the national Spanish government, Mas announced that Catalans will instead have the option to participate in a non-binding ‘consultation.’

From referendum to ‘consultation’

In substance, the informal ‘consultation’ isn’t incredibly different than the formal vote that Mas (pictured above) and the Catalan regional parliament initially scheduled, given that Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy denounced the vote and questioned the ability of Mas or a majority of the Catalan parliament to call a referendum legally. Spain’s constitutional court ruled the referendum unconstitutional at the end of September, and Mas originally declared that the vote would go forward.

* * * * *

RELATED: In refusing Catalan vote,

Rajoy risks isolating himself and Spain’s future

RELATED: Can Felipe VI do for federalism what

Juan Carlos did for democracy?

* * * * *

Mas’s admission this week that the vote will be informal and non-binding reduces many of the tensions with Madrid, though the original vote wasn’t entirely binding, either. But his announcement may dampen his credibility with pro-independence Catalans (critics took to Twitter to declare it was ‘game over’ for Mas) and force the third regional election in four years.

Nevertheless, the referendum will still ask Catalan voters the same two questions as before:

Do you want Catalonia to be a state?

If so, do you want Catalonia to be an independent state?

No matter what happened on November 9, no one believed that the issue of Catalan sovereignty would be definitively settled anytime soon. A significant vote in favor of Catalan independence, which will now be held in Catalan municipal buildings without national Spanish oversight, could pressure Rajoy’s government to devolve further power and greater fiscal autonomy to the Catalan government, a step that Rajoy has refused to countenance.

Deep questions about Catalan sovereignty will linger

long after November 9

Rajoy’s refusal to negotiate with Mas is widely seen as a snub against the vast majority of Catalan regional lawmakers who supported the referendum. That, in turn, has arguably emboldened the cause of Catalan nationalism. Rajoy is now the obstacle to holding an open, free and fair vote, a stand that has offended even anti-independence Catalans. In that regard, Rajoy suffered mightily from the Scottish contrast, where British prime minister David Cameron (pictured above, right, with Rajoy, left), however reluctantly, agreed to the terms of an independence vote more than a year in advance with Scottish first minister Alex Salmond. Rajoy and Mas haven’t even met to discuss matters since the end of July.

Rajoy’s recalcitrance has fueled the notion that he doesn’t care to address the many valid issues concerning the structure of Spanish government and the economic and social autonomy of Catalans. Though Rajoy tried to strike a conciliatory note after Mas’s announcement (even penning a Catalan language opinion piece in El Pais), he didn’t fundamentally budge from his position that a Catalan referendum is unconstitutional:

“I don’t know what it is that’s been announced for November 9 exactly, but there are no criteria other than dialogue and the law,” said Rajoy…. “If we see there are things [about this other vote] that go against the law, we will have to appeal them,” he added. The PP has already appealed the original referendum before the Constitutional Court, saying it is illegal because it deprives all Spaniards of the right to vote on a matter of national importance.

Nevertheless, a debate is long overdue over the issue of Spanish federalism. Many Rajoy advisers believe that it’s not the best time for that debate, given the economic trouble that Spain continues to weather, and that those conversations should not take place under the penumbra of the worst economic distress in decades.

But the chief gripe that Catalans have with Madrid is economic, and it’s a gripe that’s amplified during the current crisis. Catalunya is one of the wealthiest regions of Spain (contributing around 20% to Spanish GDP), and it also sends much more in tax revenues to the central government than it receives in return in the form of public expenditures. With 7.5 million of Spain’s 47 million residents, Catalans have become especially sensitive during the latest economic downturn to subsidizing less productive regions. While unemployment is generally lower in Catalonia (20%) than the national rate (24.4%), the past five years have been difficult for Catalans as well as other Spaniards.

Though the Scottish independence movement garnered more headlines, the Catalan nationalist movement actually has a much deeper tradition, based on far more troubling differences, and it ultimately could fuel a greater separatist crisis in Europe. An independent Scotland might initially struggle, but it would leave behind a rump United Kingdom with strong economic fundamentals. Catalan independence, however, would leave behind an ever-struggling rump Spanish state in poorer economic condition.

Nevertheless, the fight between Barcelona and Madrid goes far beyond fiscal policy. While the last major conflict between Scotland and England was the War of the Rough Wooing in the 1540s, Catalunya suffered throughout much of the middle of the 20th century at the hands of Spain’s fascist leader, Francisco Franco. Catalan nationalists were jailed, tortured and killed, and the Francoist regime suppressed Catalan culture and the Catalan language. Even today, Catalan isn’t an official language in Spain (though it is within Catalunya), which contributes greatly to the collective chip on the Catalan shoulder. An attempt to introduce education reforms in 2012 that would have emphasized Spanish-language instruction only exacerbated the issue. Unlike in Scotland, where virtually no one speaks Scottish Gaelic as a first language, an independent Catalunya could hope to elevate Catalan to the level of official EU language.

Snap elections and a Catalan shift leftward?

There are few good options for any of the key players. Though Rajoy has won the battle, Catalan sovereigntists (including hardcore nationalists much more extreme than Mas) may yet win the war.

Rajoy still seems tyrannical to many Catalans (including federalists), because he hasn’t acknowledged the reality that the Spanish government must eventually open a dialogue with Catalunya — and possibly also the Basque Country/Euskadi or even other autonomous regions, like Rajoy’s native Galicia or the southern Andalusia — about a more federal structure for Spain.

Rajoy will face an uphill battle in next year’s national parliamentary elections amid a highly fragmented political scene that’s developed into from a chiefly two-party system to a more multi-party system since Rajoy’s center-right Partido Popular (PP, People’s Party) won the December 2011 elections. Rajoy’s chief opponent, the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), also opposed Mas’s referendum. But its new leader Pedro Sánchez, has taken a softer line than Rajoy over the Catalan question, admitting the need for a constitutional solution.

Mas, however, might emerge weaker than anyone, because his middle ground is unlikely to satisfy anyone.

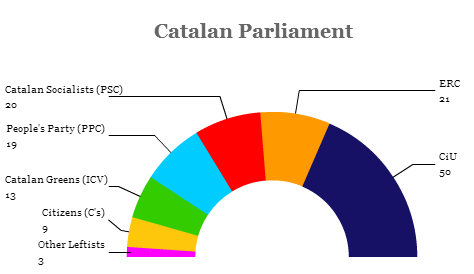

Catalan regional politics are highly complex, with at least four major parties, each occupying a different place on the separatist/federalist axis and the traditional left/right axis, and up to three more middle-level parties that could play a material role in the next elections.

Mas leads a coalition of two center-right parties, Convergència i Unió (CiU, Convergence and Union), which have historically been more autonomist than pro-independence, and which have controlled Catalan government since 1980, with the exception of a center-left government between 2003 and 2010.

Mas returned the CiU to power in 2010 and won reelection narrowly in 2012 (after trying to use the sovereignty issue to bolster his standing). But because CiU has been in government throughout the worst of Spain’s fiscal crisis, it has had to take politically unpopular decisions with respect to budget cuts. CiU is also suffering from revelations of corruption by its former leader Jordi Pujol, who led Catalunya’s government between 1980 and 2003, and who apologized earlier this summer for maintaining secret bank accounts amid rumors of widespread graft during his 23-year reign.

Until Mas effectively cancelled the referendum, he governed in coalition with the Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC, Republican Left of Catalonia), a leftist and stridently pro-independence party led by Oriol Junqueras (pictured above), a historian, who has now called on Mas to declare early elections. Polls show that, unlike in the 2012 regional elections, when Mas’s CiU won the largest share of the vote, the ERC would today become the largest party in the Catalan parliament. That could, ironically, make the regional government even more pro-independence, forcing the constitutional showdown with Madrid that Mas has tried to avert and that Rajoy should be desperate to avoid as national elections approach.

Mas, fearing that he could lose regional elections to a party with greater nationalist credibility that can also run on an anti-austerity campaign, would prefer to form a new coalition with the Catalan variant of Spain’s chief center-left party, the Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC-PSOE, Socialists’ Party of Catalonia).

Rajoy’s party also has a local presence in the form of the Partit Popular de Catalunya (PPC, People’s Party of Catalonia). The federalist Ciudadanos – Partido de la Ciudadanía (C’s, Party of the Citizenry) has a substantial voter base, as does the socialist Iniciativa per Catalunya Verds (ICV, Initiative for Catalonia Greens). In the next Catalan election, however, the anti-unemployment movement, Podemos, could also attract significant support.