The problem with South Africa’s opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), has always been that it is viewed as a party for wealthy whites — even when its former leader, Helen Zille, was a longtime anti-apartheid journalist. ![]()

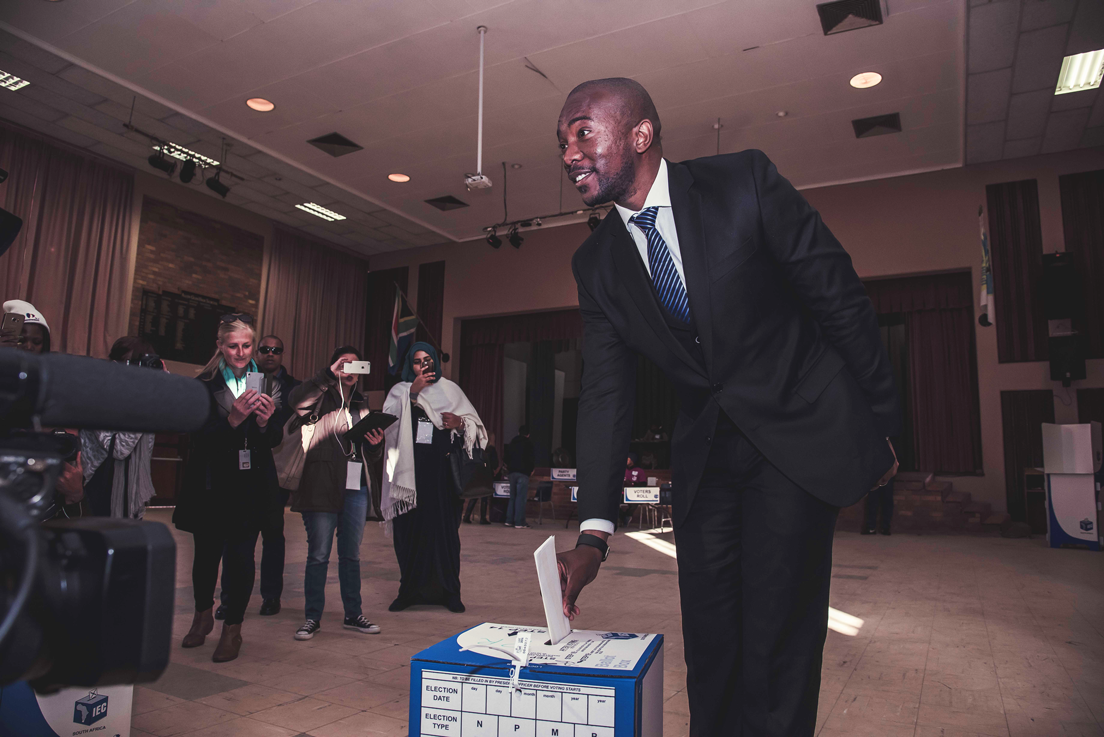

The rap on the DA’s new leader, Mmusi Maimane, is that the 36-year-old was far too inexperienced to navigate the South Africa’s complicated racial politics, long dominated in the post-apartheid era by the African National Congress (ANC). Even under Maimane’s leadership, ANC leaders and others routinely slam the Democratic Alliance, somewhat unfairly, for a ‘legacy of racism.’

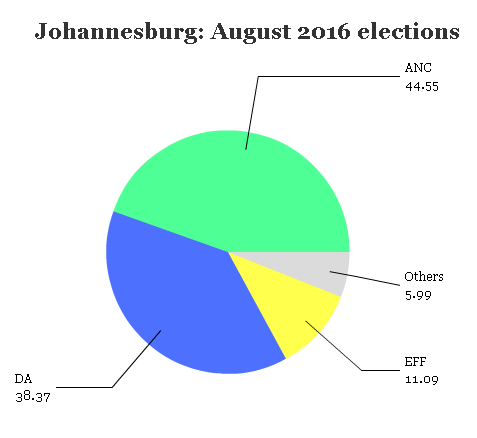

But the DA’s success in last week’s municipal elections may force South Africans to reconsider their views both about the party and its young leader. Voters across the country recoiled at the economic malaise, corruption and other shenanigans that have accumulated under Jacob Zuma, the country’s president since 2009, handing several victories to the DA, which fell just shy of winning in Johannesburg, South Africa’s most populous city.

In the May 2014 general election, the Democratic Alliance had its best showing to date, even though it meant winning just 22.23% of the vote nationwide, compared to 62.15% for the ruling ANC. Historically, the DA has managed to attract a wide majority in Western Cape province and in the city of Cape Town, but it has struggled elsewhere in an uphill battle to convince voters to abandon the ANC, the party of Nelson Mandela that’s still synonymous with the end of apartheid.

More than two decades after the ANC came to power, however, unemployment is on the rise, GDP growth has slowed, and Zuma faced a rebuke earlier this spring from South Africa’s top constitutional court, which ordered him to repay some of the $23 million in public funds that Zuma spent to renovate his Nkandla home. One of the much-hyped BRICS economies, South Africa hasn’t achieved GDP growth over 4% since 2007, and growth slowed increasingly in the past three years — the economy is expected to grow by just 0.1% this year.

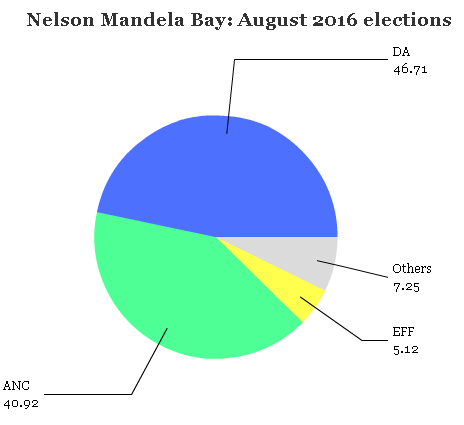

Election officials confirmed late last week that the Democratic Alliance won in Nelson Mandela Bay, a municipality that includes Port Elizabeth, the largest city of Eastern Cape province.

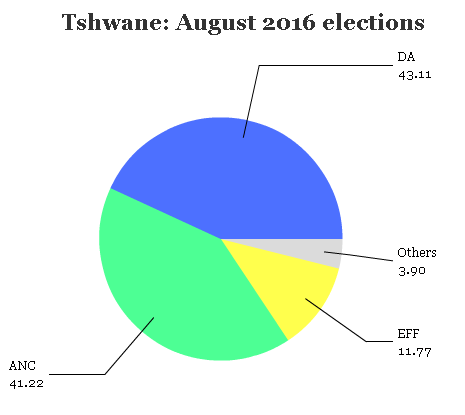

Over the weekend came even more stunning news that the Democratic Alliance narrowly edged out the ANC in Tshwane municipality (which includes Pretoria, South Africa’s administrative and executive capital) and only narrowly lost Johannesburg. Both cities are in Gauteng province, which has been a Maimane target for a while, dating back to his own mayoral run in Johannesburg in 2011.

Voters across the country voted on August 3 for municipal councils at several levels of government. The largest prizes include the councils of eight metropolitan municipalities, which include South Africa’s most populous cities.

Voters across the country voted on August 3 for municipal councils at several levels of government. The largest prizes include the councils of eight metropolitan municipalities, which include South Africa’s most populous cities.

In addition to Nelson Mandela Bay, Tshwane and Johannesburg, those eight municipalities also include the DA-controlled Cape Town and four additional councils that the ANC easily retained (including, for example, the eThekwini municipality that includes Durban).

The results mean that the DA (in Pretoria and Port Elizabeth) and the ANC (in Johannesburg) will both scramble either to align with the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) or to try to govern with a minority.

The results mean that the DA (in Pretoria and Port Elizabeth) and the ANC (in Johannesburg) will both scramble either to align with the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) or to try to govern with a minority.

The EFF, an ANC breakaway group led by former ANC rising star and one-time Zuma protege Julius Malema, advocates a hard-left redistribution program of land and resources to black South Africans. On the one hand, Malema and the EFF have joined forces with the Democratic Alliance to protest the corruption and abuses of the Zuma regime, working together earlier this year on a motion to impeach Zuma. On the other hand, however, it’s nearly impossible to imagine much common ground between the EFF and the Democratic Alliance. That means there’s a possibility that a united ANC-EFF front could govern Johannesburg and even Tshwane (despite the ANC’s second-place finish). Furthermore, in the long run, a post-Zuma ANC might find a way to bring Malema and his band of radical socialists back within the ANC umbrella.

Notwithstanding municipal coalition talks, Maimane and the Democratic Alliance hope the local election results will be a springboard for real progress in the next general election. Somewhat audaciously, the DA tried to cast itself in 2016 as the true heir to Mandela, prompting anger from the ANC and even the Mandela family itself.

The DA hopes that it can showcase its vision for government in Port Elizabeth and, possibly in Pretoria, giving the party credibility throughout Eastern Cape and Gauteng, respectively. The problem for the DA is that the next general election doesn’t take place until 2019. By then, Zuma will no longer be leading the ANC, which will choose its new leader at its national conference next year.

Despite the DA’s gains, the August local elections were more a referendum on Zuma than anything else. The EFF’s share of the vote also increased from the 2014 election, and Malema will be sure to relish his new role as a municipal council kingmaker. But even in KwaZulu-Natal, Zuma’s home and power base, the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) — a local party that fought violently in the 1990s with the ANC — made gains as well. Indeed, the IFP even won Zuma’s home council in Nkandla.

In Tshanwe, in particular, the ANC’s decision to cast aside the incumbent mayor, Kgosientso Ramokgopa, in favor of a fresher face, Thoko Didiza, led to riots last month across Pretoria and fresh concerns about growing factionalism, ethnic and otherwise, within the ruling ANC. In Johannesburg, incumbent mayor Parks Tau, a rising ANC star, is far more popular than Zuma, and his efforts likely contributed to the ANC’s narrow victory.

All eyes now turn to the national conference in 2017. For now, two familiar faces dominate the discussion. One is Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, the current president’s ex-wife, a former health minister and home minister who recently decided not to run for a second term as the chairperson of the African Union Commission. The other is Cyril Ramaphosa, deputy president since 2014 and a one-time rival to former president Thabo Mbeki. Ramaphosa returned to politics in 2012 after over a decade in business.

It’s also possible that as the ANC focuses on next year’s conference, a younger — and perhaps more inspirational — candidate will emerge.

Zuma certainly prefers Dlamini-Zuma, who would shield her former husband from many of his ongoing legal battles. She would begin the race with support from within the ANC and from Zuma’s home province of KwaZulu-Natal. Ramaphosa, who belongs to neither of South Africa’s leading ethnic groups (the Zulu and the Xhosa), nevertheless has the not-so-covert backing of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), which is part of the ‘tripartite’ alliance (along with the ANC and South African Communist Party) that’s governed South Africa since 1994. COSATU’s leaders have been increasingly critical of the Zuma administration in recent years.

Ramaphosa, more than Dlamini-Zuma, could credibly argue that his leadership of South Africa would mark a firm break from the Zuma years. Moreover, Ramaphosa’s private-sector experience will give him credibility with South Africa’s business class, and his ties to Mandela (he was part of the ANC committee that negotiated the end of apartheid) will stem the DA’s efforts to appropriate Mandela’s legacy.

The median age in South Africa today is 25.7 years, which means that many voters no longer remember what it was like to live under apartheid. Increasingly, many of those young voters see the ANC not as the guarantor of racial equality in South Africa, but a corrupt juggernaut that cannot deliver on its promises of jobs and economic prosperity. That is good news for Maimane and the Democratic Alliance, though no one would place any bets that the DA can win in 2019. But it’s also good news for South Africa, which would be well-served from a transition from effective one-party rule to multi-party politics.