Back in July, I suggested that Park Geun-hye (박근혜) of the Saenuri Party (새누리당 or the ‘Saenuri-dang’, the New Frontier Party) was defying gravity in her race for South Korea’s presidency, and I listed five reasons why:

- She’d rebranded her party from the Grand National Party into the ‘New Frontier’ Party.

- She then led the Saenuri Party to victory in elections for the National Assembly in April despite the unpopularity of her party’s incumbent president Lee Myung-bak (이명박).

- Even six months ago, she had already co-opted the message of the center-left on ‘economic democratization,’ chaebol reform and income inequality.

- South Korea’s progressive opposition was largely divided.

- Mixed feelings (including some nostalgia among older voters) about her father’s authoritarian reign from 1961 to 1979 largely neutralized potentially controversial family ties.

By the time South Koreans went to the polls yesterday, all of those factors contributed to her victory.

She has defeated Moon Jae-in (문재인) of the Democratic United Party (민주통합당, or the ‘Minju Tonghap-dang’) with 51.6% of the vote to just 47.9% for Moon, ending what was always a very close race — albeit one where Park always seems to hold a slight edge.

As we look ahead, all of those factors should equally inform us as to what to expect from Park — the first woman to become South Korea’s president — and her incoming administration.

By rebranding her party as the ‘New Frontier’ Party — and making clear that the new frontier would not include Lee (who narrowly defeated Park for her party’s presidential nomination in 2007) — and then running against Lee’s record as much as against her opponent, she neutralized one of the most significant impediments to her candidacy. She reinforced the split during the spring legislative campaign — and, by the way, she’ll enter the Blue House with a very friendly parliament as well. Moon, had he won the election, would have been hampered by a hostile Saenuri majority, but Park will find a largely pliant National Assembly — Saenuri legislators know that they would not have that majority without Park. So she’ll wield significant power as president in order to push through her campaign agenda.

That agenda, frankly, does not appear dissimilar to the agenda Moon promised. While the policy details have been less than detailed, Park’s campaign emphasized traditionally liberal themes, and that moderate agenda certainly helped elect Park yesterday. If Park wants to avoid the unpopularity of her predecessor, she’ll have to produce legislative accomplishments, not only on chaebol reform, but also find a way to reduce Korean income inequality and, ultimately, she’ll probably need to be lucky enough to have robust GDP growth.

On North Korea, too, both candidates agreed that the next president should be more conciliatory to North Korea than Lee’s administration, but they shied away from advocating a full return to the ‘Sunshine Policy’ of the late 1990s and 2000s that increasingly seemed to South Koreans like a series of handouts in exchange for further aggression from North Korea. So under Park, South Korea will likely retain its firm approach to North Korea, but with relatively more carrots than sticks.

In terms of the geopolitics of East Asia, Park — who assumed the role of first lady during her father’s administration at age 22 when, in 1974, her mother was assassinated by North Koreans — will certainly be no shrinking violet (get set for five years of hearing the phrase ‘the Iron Lady of Asia’).

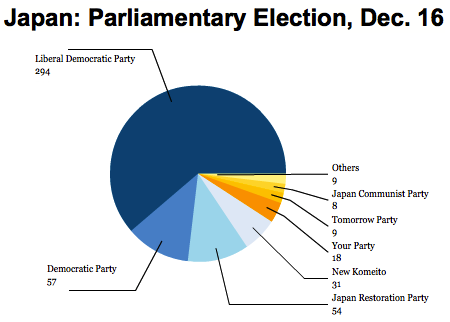

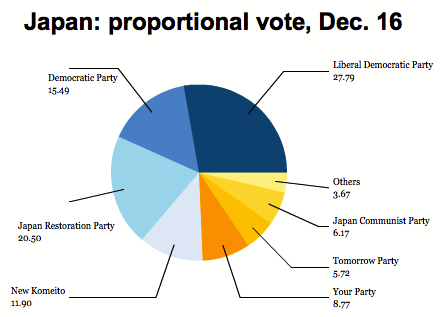

Indeed, it’s a crucial time for East Asia, given that King Jong-un has been in power for only a year, Xi Jinping (习近平) only last month took over as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) and is set early next year to become the president of the People’s Republic of China, and the hawkish Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) only last Sunday won Japan’s parliamentary elections, returning him to power as prime minister. Park’s immersion in Korean politics since the 1970s and her perceived toughness (she once returned to the campaign trail in 2006 just days after an assailant slashed her in the face with a knife) also likely contributed to her victory yesterday. Continue reading Park Geun-hye becomes South Korea’s first female president