Czech voters returned to the polls yesterday and today for the runoff in the Czech Republic’s first direct election for president.

Former social democratic prime minister Miloš Zeman has defeated the current more conservative foreign minister Karel Schwarzenberg by a margin of around 54.8% to just 45.2% for Schwarzenberg.

Schwarzenberg emerged as a surprise challenger to Zeman after the first round, edging out former prime minister Jan Fischer, setting up a runoff that featured two candidates with incredibly colorful personalities.

Schwarzenberg, who belongs to the Bavarian nobility, spent much of his life in Austria, where his family lived in exile during the Communist occupation of Czechoslovakia, increasingly fighting in the 1980s alongside Václav Havel to liberate the country from Soviet rule. As the leader of the Tradice Odpovědnost Prosperita 09 or ‘TOP 09′ (Tradition Responsibility Prosperity 09), which he formed for the 2010 Czech parliamentary elections, his party is the second-largest member of the coalition headed by prime minister Petr Nečas, the leader of the Občanská demokratická strana (ODS, Civic Democratic Party).

Zeman, formerly a prime minister from 1998 to 2002 from the Czech Republic’s main center-left party, the Česká strana sociálně demokratická (ČSSD, Czech Social Democratic Party), is known for his sharp wit and aggressive persona, but lost his first run for the presidency in 2003 to the outgoing incumbent, Václav Klaus. Zeman, at odds with the current ČSSD leadership, left the party in 2009 to form his own.

While Schwarzenberg peaked at the end of the first round, and certainly entered the second round with a bit of momentum, it wasn’t enough to power a 75-year-old aristocrat with a penchant for napping, into the Czech presidency.

It certainly didn’t help that Schwarzenberg spent three decades outside of the country and his Czech language skills were sometimes seen as less than pristine, and Zeman’s campaign took advantage of the perceived ‘otherness’ of his opponent.

Zeman’s supporters even intimated, despite any evidence, that Schwarzenberg’s family collaborated with Nazis.

World War II featured as an issue in a debate between the two candidates when Schwarzenberg claimed that the Beneš decrees, which dealt with the expulsion of ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II would today be considered a war crime, and Zeman responded by attacking Schwarzenberg as a Sudaten German himself.

Zeman and Schwarzenberg both achieved endorsements from unlikely sources in the second round.

Despite their ideological differences, Zeman long ago won Klaus’s endorsement (Klaus also enabled Zeman’s prime ministerial term in 1998 when he agreed to support the government in exchange for patronage and government positions for the ODS). Zeman and Klaus belong to the same generation of Czech political leadership, and many see in Zeman a lot of the same qualities as Klaus, who has been outspokenly conservative as president, outspokenly eurosceptic and even cast doubts on the validity of manmade climate change.

Fischer, who could have been expected to endorse Schwarzenberg as a more center-right candidate, failed to do so. He didn’t endorse Zeman, but he said that he could not vote for Schwarzenberg.

Furthermore, the official ČSSD candidate, Jiří Dienstbier Jr., who finished a surprisingly strong fourth place in the first round, said that he could not vote for Zeman.

Although other ČSSD leaders endorsed Zeman, they were certainly less than enthusiastic in their support. Although it’s likely that Zeman won the share of ČSSD voters, his win today makes it likely that the next five years will feature an awkward relationship between Zeman’s camp and the formal ČSSD leadership.

The tattooed fifth-place finisher, Vladimír Franz, endorsed Zeman, after attracting worldwide attention in advance of the first round. Although Franz’s voters likely leaned to the left, they were younger and urban, a constituency to which Schwarzenberg appealed — Zeman’s voter base featured older and more rural voters.

Although Havel, who served as president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 to 1993 and, after the 1993 breakup of the union, the Czech Republic, until 2003, wasn’t as universally popular within the Czech Republic, I wonder if the election would have turned out differently if Havel were still alive to endorse and campaign for his longtime friend Schwarzenberg. Havel died just 13 months ago in December 2011.

Ultimately, the massive unpopularity of the Nečas government, certainly made a Schwarzenberg victory an uphill challenge, given the double misery of a troubled economy and, like in many European countries these days, pursuing a policy of budget cuts and economic reform. In the first round, the official ODS candidate, Přemysl Sobotka, a senator, won just 2.46% and placed eighth out of nine candidates.

![]()

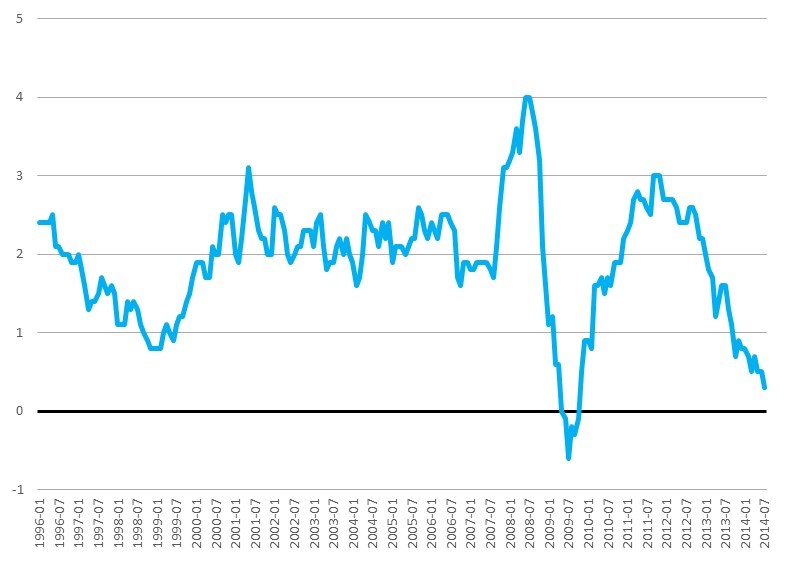

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much more active ‘QE-style’ approach to the bank’s balance sheet — in part by moving last month to purchase private-sector bonds and asset-backed securities. Even if Draghi’s efforts still fall short of the kind of quantitative easing (e.g., outright asset purchases) that the Federal Reserve introduced to US monetary policy five years ago, Draghi committed himself to lifting the eurozone’s inflation from ‘its excessively low level’:

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much more active ‘QE-style’ approach to the bank’s balance sheet — in part by moving last month to purchase private-sector bonds and asset-backed securities. Even if Draghi’s efforts still fall short of the kind of quantitative easing (e.g., outright asset purchases) that the Federal Reserve introduced to US monetary policy five years ago, Draghi committed himself to lifting the eurozone’s inflation from ‘its excessively low level’: