Central America holds its fair share of elections over the coming months, starting with the November 24 general election in Honduras, where voters will select a new president and all 128 legislators in the Congreso Nacional (National Congress).

But that’s just the beginning — El Salvador holds the first round of its presidential election in February 2014, with a potential runoff in March 2014, Costa Rica holds a general election in early February 2014, and Panamá holds its general elections in May 2014. Guatemala will hold off until autumn 2015 and Nicaragua and Belize will hold off until 2016, when president Daniel Ortega (yes, that one) may well attempt to cling to power.

What’s more, in each of the four Central American elections set to take place in the next seven months, presidential term limits prohibit the incumbent from reelection, so four countries with over 21 million people will make political transitions of some kind.

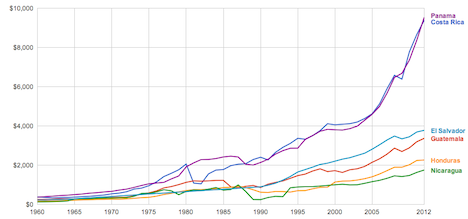

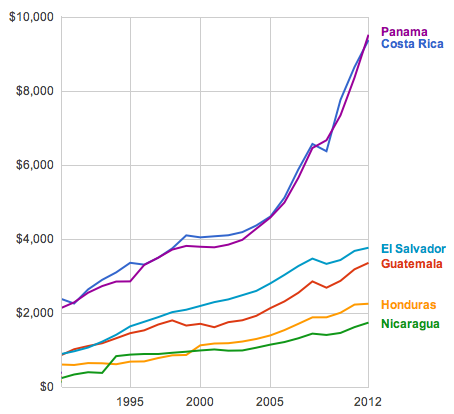

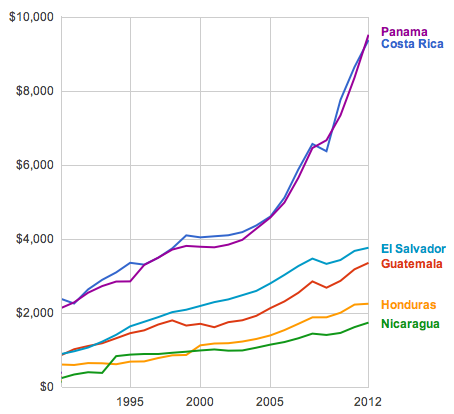

But what’s most staggering is that the issues in each of the four elections are massively different — GDP per capita varies widely. Though you can see a slight variance in 1960 setting Panamanian and Costa Rican GDP per capita apart, Guatemala briefly overtook Costa Rica in the early 1980s and Nicaragua was also on essentially the same path as Panamá and Costa Rica before flatlining for a decade starting in the late 1970s (following the Managua earthquake and anticipating the fall of the Somoza regime) and actively falling during the 1980s and early 1990s when the Cold War-inspired civil war devastated the country. Though El Salvador continued to growth at a slow, steady rate throughout its civil war, which raged from 1979 to 1992, its growth rate exploded in the mid-1990s, and pushed the country to appreciably higher standards of living than its neighbors.

Still, the greatest relatively gains have been made over the past two decades:

Costa Rica, with its tourism (and its position as a regional hub for Intel microprocessors), and Panamá, with its canal revenues, banking and insurance sectors and, increasingly, also tourism, lead the way. Panamá City long overtook Managua as Central America’s financial hub.

In short, Panamá and Costa Rica are becoming tropical extensions of North America, with GDP per capita approach $10,000, essentially equivalent to that of México, and just a little lower than Brazil, Argentina, and Chile.

The remaining four countries major countries (minus Belize) are languishing further behind, with some of the lowest standards of living in all of Latin America.

Especially in Honduras, which features the higher homicide rate in the world — a rate that’s more than doubled since 2005 from around 37 homicides per 100,000 to 91.6 in 2011. The World Bank estimates that violence and crime levels cost Honduran economy about 10% of GDP annually. Security dominates the election campaign, but it’s a real drag on the economy as well.

Nonetheless, the economy has grown steadily at around 3.5% for the past four years, in part due to the strength of its export economy, fueled by the passage of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) among the United States, Honduras, the Dominican Republic and several other Central American countries. That has boosted the maquila (assembly) industry, as well as other service and manufacturing sectors in Honduras — agriculture remains important, but bananas represent just about 3.5% of exports in the original ‘banana republic,’ and coffee amounts to just 10% of exports. The economy remains incredibly tied to the United States — exports to the United States account for about 30% of Honduran GDP and remittances from the United States and elsewhere contribute about 20% of Honduran GDP.

But whereas economists and observers once joked that Honduras was so poor that it couldn’t even afford an oligarchy, it now has the highest Gini coefficient in Central America (57) and one of the highest in the world as inequality continues to rise. About 60% of Hondurans live below the poverty line. Moreover, corruption remains a real impediment to foreign investment — Transparency International ranked the country 133rd in 2012, again the lowest score in Central America (and just barely topping the more lowly ranked Venezuela).

In global terms, however, Honduran GDP per capita (around $4,600 on a PPP basis), is relatively wealthy — that’s still higher than in India, Pakistan, Vietnam, Nigeria, Kenya or Ethiopia.

![]()