Whenever I go to México City, I marvel at the way its indigenous history integrates into the fabric of the city. Nahuatl words, like ‘Chapultepec,’ meaning grasshopper, and ‘Xochimilco,’ a neighborhood featuring a series of Aztec-created canals, pepper the geography of the city. Those are just two of hundreds of daily reminders rooting Latin America’s largest modern megapolis of 8.9 million in the language and traditions of its pre-Columbian past. It’s where the Virgin of Guadalupe, a young Nahuatl-speaking girl, apparently revealed herself to Juan Diego in 1531 as the Virgin Mary, instructing him to build a church, launching one of the most compelling hybrid religious followings in the New World. Even the inhabitants of the notorious Tepito barrio worship Santa Muerte on the first of November with bright flowers, cacophanous marimba and not a small amount of marijuana, in celebration of the magical chasm between what is, for many Tepito residents, a gritty life and an often grittier death.

It’s the way that México City blends the mysterious and the mundane, matches the sacred with the profane and so blends the line between the indigenous and conquistador that it’s hard to know who conquered what. For all of those reasons, I often think of it as the unofficial capital of realismo magico.

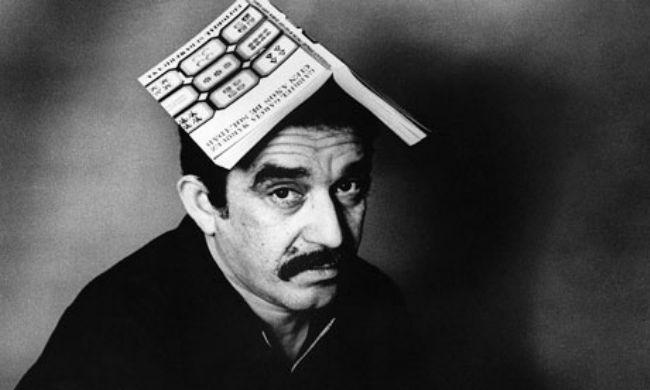

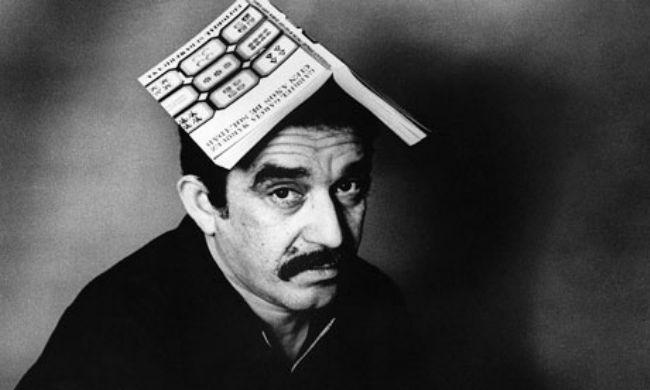

So it’s natural to me that the literary master of magical realism, Gabriel García Márquez, made his home in México City for much of the last six decades of his life. It’s also where García Márquez died on April 17 at age 87.

It was his uncanny ability to blend the realistic with the magical that largely won him such adoration worldwide. But what makes the writing of García Márquez and the other authors of the 1960s Latin American Boom so electrifying to me is the way that it blended the literary with the political. Certainly, García Márquez’s writing was about family, about love, about solitude, about power, about loss, about fragility, about all of these universal themes. But his writing also explicated many of the themes that we today associate with Latin America’s culture, identity, history and politics.

His death wasn’t entirely unexpected. García Márquez was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer all the way back in 1999 and by the beginning of the 2010s, he rarely made public appearances anymore due to the grim advance of Alzheimer’s disease. By the time I made it to Latin America for the first time, he was already approaching 80, and I knew I’d have little chance of meeting him.

That’s fine by me, because I always considered him, through his work, my own personal ambassador to Latin America. Over the course of several treks through Latin America, Gabo still accompanied me through his writing — and along the way, he shaped my own framework for how I think about Latin American life.

* * * * *

When I was planning my first trip to Latin America, I brought with me a copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude. I saved the novel for this very occasion, a trek from Buenos Aires to Mendoza and then by bus over the Andes to Santiago. Technically speaking, I was on the wrong end of the continent for García Márquez. I packed some Neruda, some Allende and some Borges — and some Cortázar, too (mea culpa, I still haven’t clawed enough time to read Hopscotch).

Nevertheless, García Márquez’s words transcended the setting of his native Colombia. Hundred Years, published in 1967, just six years after the Cuban revolution that undeniably marked a turning point in its relationship with the behemoth world power to the north, it came at a time when Latin American identity seemed limitless, and García Márquez mined a new consciousness that wasn’t necessarily Colombian or even South American. So much of the story of Colombia’s development from the colonial era through the present day is also cognizably Bolivian, Chilean, Mexican or Argentinian. After all, García Márquez, already a well-known figure, went on a writing strike when Augusto Pinochet took power in Chile in 1973, ousting the democratically elected Socialist president Salvador Allende, who either committed suicide or was shot on September 11, the day of the coup.

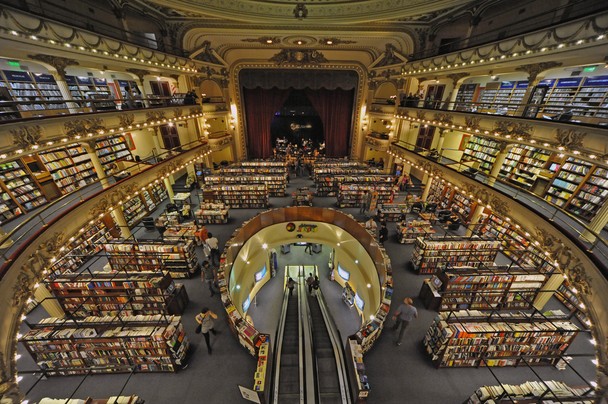

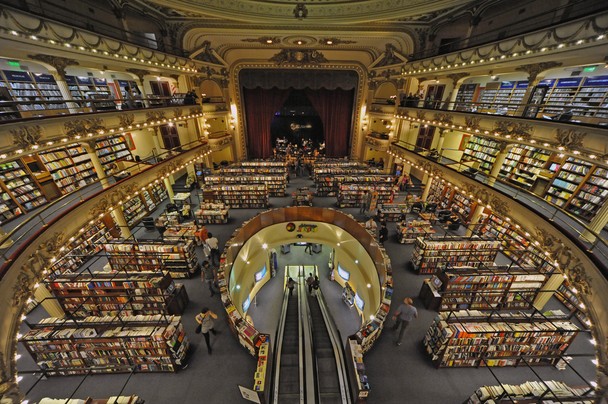

It was an intoxicating read. The sleek brown corduroy blazer I picked up in Buenos Aires with the affected hint of epaulets on the shoulders soon became what I called my ‘Colonel Aureliano’ jacket. Besides, where better to buy a Spanish language copy of his work than El Ateneo, perhaps the most amazing bookstore in the world?

* * * * *

Hundred Years, of course, came highly recommended from the world that had discovered García Márquez decades before I was even born. It became an instant hit upon publication, catapulting García Márquez’s popularity beyond his more established peers, including México’s Carlos Fuentes and Perú’s Mario Vargas Llosa.

Bill Clinton, in his autobiography My Life, confesses to zoning out of class one day in law school to finish it: Continue reading ESSAY: How Gabriel García Márquez introduced me to Latin America →

![]()

![]()