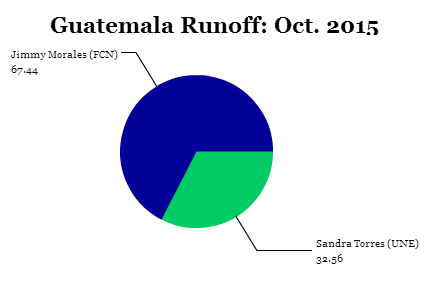

As expected, former comic actor Jimmy Morales won Guatemala’s presidential runoff Sunday, besting former first lady Sandra Torres by a margin of more than two-to-one.![]()

Riding a wave of widespread popular discontent with a political elite widely seen as corrupt — including former vice president Roxana Baldetti and former president Otto Pérez Molina, both of whom are in jail pending corruption charges — Morales easily captured the presidency with over 67% of the vote.

*****

RELATED: Polls give Morales a lock on Guatemala’s presidential runoff

*****

That was the easy part.

As a political neophyte, Morales will have a steep learning curve in office, especially if he wants to carry forward the agenda of electoral and political reforms that can could make Guatemala’s government more permanently transparent and accountable.

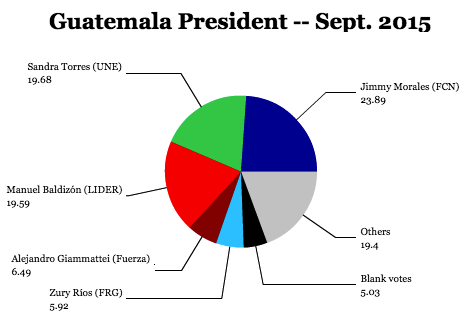

Though he ran under the banner of a small conservative party founded a few years ago by retired conservative generals, the Frente de Convergencia Nacional (FCN, National Convergence Front), it holds just 11 seats in Guatemala’s unicameral Congreso (Congress). That means that Morales is going to have to build a congressional majority nearly from scratch. The good news is that Guatemala’s political parties are so personality-driven that the collapse of Pérez Molina, Torres and former presidential frontrunner Manuel Baldizón means there will be ample room for legislators to join the Morales bandwagon. The bad news is that many of those legislators are part of Guatemala’s corruption problem, and they have no incentive to enact reforms that will make graft even more difficult and establish roadblocks to the political financing they will need to further their own political careers.

Meanwhile, Morales’s landslide obscures the fact that a lot of Guatemalans — even those who voted for him — are worried about the right-wing flavor of his campaign. Though Morales attracted a broad coalition of voters who are eager to flush the corrupt political elite out of power, there’s far more hesitation about Morales himself.

A socially conservative evangelical, Morales is anti-abortion, anti-LGBT rights and he has the support of much of the military elite, through the FCN and otherwise. He’s argued for the outright annexation of Belize, for example, and he’s otherwise embraced nationalist positions. Other critics point out that many of his skits, over a long career in television, are rooted in racial and ethnic stereotypes, which could breed distrust among indigenous Mayan and other communities that have often been mistreated by Guatemala’s military and democratic governments alike.