He is in many ways an accidental man of the moment, the man standing on stage who can most credibly claim, as his slogan goes, that he is ni corrupto ni ladrón — ‘neither corrupt nor a thief.’![]()

Jimmy Morales, the 46-year-old former comedian, who just a few years ago graced shampoo bottles across Guatemala in an afro wig and blackface, is now the overwhelming favorite to win the country’s presidential runoff on Sunday, October 25, with one recent poll for the Prensa Libre giving him 67.9% of the vote to just 32.1% for the former first lady, center-left Sandra Torres. Other polls show similar gaps in Morales’s favor.

*****

RELATED: Torres edges Baldizón into Guatemalan runoff with Morales

RELATED: The contour of Guatemala’s new Congress is very conservative

*****

Barring a complete change of heart, Morales will become Guatemala’s next president.

So who is he and what does he believe? How did a comic actor wind up leading Central America’s largest economy? Most importantly, what will his election mean for Guatemala’s future?

The extraordinary background to Guatemala’s presidential election lies in the 2006 creation of the UN-sponsored Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG). Slowly, and with several extensions of its mandate, CICIG uncovered a wide-ranging customs fraud scheme, referred to in Guatemala as La Línea, forcing many of the government’s ministers to resign. In May, the investigation ensnared vice president Roxana Baldetti, who resigned and is now under indictment for corruption. Finally, after Guatemala’s Congress voted to strip then-president Otto Pérez Molina of his executive immunity just days before the first round of the 2015 elections, Pérez Molina resigned and is now also facing corruption charges. In testimony in a related trial, one businessman stated that Pérez Molina and Baldetti received up to 50% of all bribes provided by importers into the Guatemalan market.

*****

RELATED: Three days before elections,

Pérez Molina resigns after arrest warrant issued

*****

Just days after Pérez Molina’s resignation and subsequent arrest, Guatemalans turned out to the polls on September 6 to elect a new president and all 158 members of the unicameral Congreso.

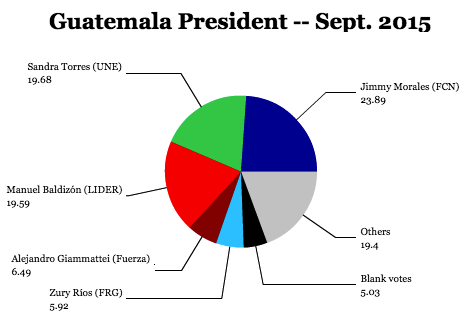

Unsurprisingly, Morales — a political neophyte untainted by the endemic corruption of official life — won a narrow majority. More surprisingly, former first lady Sandra Torres, a social democrat, edged into second place. That forced Manuel Baldizón, once the frontrunner and the runner-up of the 2011 election, out of the October runoff.

It leaves Guatemalans with something of a Hobson’s choice.

Morales has waged a campaign light on specifics because the most salient fact of his presidential candidacy is that he’s corruption-free. But behind the slogan lies a politician with some fairly conservative and populist views. In a debate between the two runoff candidates earlier this month, Morales suggested that Guatemala should raise the 1% royalty rate it charges on mining operations. Moreover, Morales holds fiercely conservative views on social issues like LGBT rights and abortion, which could bring him support from US evangelical groups that have long worked to cultivate ties on the Guatemalan right stretching back to the 1980s.

More troubling, perhaps, is the right-wing political party to which he joined his anti-corruption crusade. That party, the Frente de Convergencia Nacional (FCN, National Convergence Front), has strong ties to some of the retired generals who conducted a decades-long civil war during which human rights atrocities and war crimes were commonplace.

He’s also a nationalist, bemoaning the ‘loss’ of Belize and advocating its ‘return’ to Guatemala. Belize, an English-speaking country of around 350,000 people that lies to Guatemala’s immediate east, formerly the colony of British Honduras, won its independence only in 1981.

Guatemala has long claimed the southern half of the country (as divided by the Río Sibun) or, sometimes, even all of Belize — for example, Guatemalan passports show a dotted line between Guatemala and Belize. Earlier this week, campaigning kicked off in Belize for its own snap elections on November 4. Belize’s government has long urged an end to Guatemala’s quixotic territorial claim. If Morales wins the presidency, the issue’s salience will increase in Belize’s election campaign. A plan to hold joint referenda two years ago in both countries to advance the claim for adjudication before the International Court of Justice in The Hague collapsed.

Torres, who leads the center-left Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE, National Unity of Hope), is generally seen as a far better candidate in the runoff than Baldizón would have been. Baldizón, a right-wing businessman, had built from scratch his own personal political vehicle, Libertad Democrática Renovada (LIDER, Renewed Democratic Liberty), and it’s widely believed that Baldizón’s financial backers include some of the most corrupt figures in Guatemalan life, including drug traffickers. After losing to Pérez Molina in the 2011 presidential race, he soon cozied up to his one-time rival making LIDER an indispensable ally — even to the point of maintaining Pérez Molina’s immunity. Despite arguing that fraud played a role in his third-placed finish, Baldizón ended his campaign a week after the first round and stepped down as LIDER’s head.

Torres has tried to argue that Morales lacks the gravitas and the experience to run a capable administration, and she mockingly said that he would be better suited as culture and sports minister in her own cabinet. In contrast to the conservative generals who founded Morales’s FCN, Torres collaborated with the indigenous and guerrilla movements in the 1980s, and she has a strong record as an activist first lady. Focusing on social justice, she led an expansive and expensive program, the Bolsa Solidaria, to enhance social development.

But Torres carries her own baggage as well. The former wife of president Álvaro Colom, she divorced her husband in 2011 to evade Article 186 of the Guatemalan constitution, which would have prohibited her from running for a presidential term to succeed her husband; Colom himself was limited to serving just one term. Guatemala’s constitutional court invalidated the divorce for presidential purposes. Despite the gains of the Colom era in reducing poverty, Morales and other critics disparage the lack of transparency for Torres’s social programs. Funds were undoubtedly siphoned off as bribes, and Torres’s own relatives have come under investigation for embezzling state money. Nevertheless, her party has a stronger organization to get out the vote in the rural communities that benefited most from her efforts during the Colom administration.

None of Torres’s arguments seem to have outweighed the lure of electing an outsider, no matter how inexperienced.

If Morales takes office in January, he will face a divided Congress where the now decapitated LIDER holds the largest bloc of seats, with UNE holding the second-largest bloc. Taken together, the parties supporting Torres, Baldizón and Pérez Molina control 97 seats. With their leaders politically vanquished or in prison, expect a shuffling of the party decks shortly after the election.

Meanwhile, the FCN won just 11 seats, and that’s not even 10% of the Congress. That means that, if Morales wants to accomplish anything, he’s going to have to start horse-trading with the corrupt elites against whom he is running. Otherwise, it’s going to be a long and fruitless period until the next elections in 2019. If Morales cannot deliver political reform, or social and economic reform, the electorate might easily turn back to the compromised elite.

The legislative priority for Morales involves enduring electoral reform to reduce or eliminate the role of opaque campaign finance that’s made Guatemala so corrupt. Basic reforms that make political donations more transparent would help, though the state needs to have more power to police under-the-table financing as well. It will help that Morales has pledged to extend CICIG’s mandate through 2022.

Another way to tame Guatemala’s corruption is to prohibit the widespread practice of transfuguismo, whereby one congressman today will switch parties the next in exchange for a sweeter deal (politically or otherwise). That’s made it easier for parties in Guatemala to become transient, personality-oriented affairs — Colom and Torres’s UNE, Baldizón ‘s LIDER and Pérez Molina’s own Partido Patriota (PP, Patriot Party). Providing more power to party structures, instead to the petty caudillitos of the quasi-democratic era, could root Guatemala’s political discourse more in terms of policy and less in terms of patronage.