When you talk to Hondurans on the streets of San Pedro Sula, they’ll tell you they are more afraid of the police than of drug traffickers or gang members.![]()

![]()

In a county where drug traffickers offer far higher payoffs than the salaries constrained by stretched national and local budgets, today’s hero is tomorrow’s villain, and the line between good guys and bad guys has become impossible to draw. Corruption runs high and impunity runs even higher in a country where the judicial system is incapable of prosecuting a shockingly high number of violent incidents.

Yet when Honduras’s new president Juan Orlando Hernández (pictured above at the US Capitol) came to the United States last week to meet with US president Barack Obama, he pointed fingers at US policymakers for the sudden wave of child migrants from Central America to the US border seeking asylum — 57,000 this year and counting, more than 25,000 alone from Honduras.

With nearly 8.5 million people, Honduras is the second-most populous country in Central America (after Guatemala with 14.4 million) and in the current crisis, many more child migrants have arrived at the US border from Honduras than from either Guatemala or El Salvador. For example, more children have arrived from San Pedro Sula, Honduras’s northern industrial hub than from all of Guatemala. Though Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital, isn’t exactly the world’s safest city, it’s a tranquil oasis compared to San Pedro Sula and the northern coast, which is plagued with the worst of the drug-related violence that has given Honduras the world’s highest murder rate — 79.7 homicides per 100,000, amounting to around 18.5 homicides a day.

That’s one reason why the Obama administration is allegedly considering the unusual step of allowing refugees to seek asylum directly within Honduras, modeled after former programs developed for war-torn Vietnam and ravaged Haiti, a tacit acknowledgment that the human rights situation has reached dire levels.

* * * * *

RELATED: Unaccompanied minors? Blame a century of US Central American policy.

* * * * *

When Hernández came to the United States last week, he was quick to blame coyotes for turning their predatory sights to Central America, and he was quick to blame the US immigration reform debate for creating ‘ambiguity’ about US policy. But above all, Hernández noted that US demand for illegal drugs fuels the trafficking that so afflicts Honduras today:

[If] you look at the root of the problem, you’ll realize that your country has enormous responsibility for this. The problems of narco trafficking, it generates violence, reduces opportunities, generates migration because this is where there’s the largest consumption of drugs. And we’re on the route. And what happens when there’s such a high demand of drugs? Over in Honduras the gangs and the narcos are clashing, and now they fight over territory, and who’s going to move the drugs, they fight over who’s going to take the money from the other one. And that’s leaving us with such an enormous loss of life, and young people, generations of young people that we have lost because they entered the world of drugs. What is being done in the U.S. on the topic of drugs? Investigate it and you’ll see it. Here, many officials say it’s a health problem. For us, it’s a matter of life and death, and that’s not fair. What’s fair is that we work together dealing with our own responsibilities.

Correct though Hernández may be, it overlooks an even longer history of US foreign policy that’s often hampered Honduras from developing strong legal, democratic and other governance institutions, as I wrote last week:

Honduras, the original ‘banana republic,’ found successive governments of the early 20th century co-opted by US corporations (and the US department of state) to secure tax-free concessions, restrictions on labor freedom and development of exclusive roads and railways for banana plantations based on the Honduran coast, culminating in the 16-year rule of US-backed dictator Tiburcio Carías Andino in the 1930s and 1940s. Though Honduras has held regular elections since 1981, the 1980s featured paramilitary death squads that routinely targeted dissidents, and similar right-wing forces continue to harass and murder journalists, labor activists and leftists today. In 2009, a military coup ousted leftist president Manuel Zelaya when he attempted to relax the prohibition on reelection.

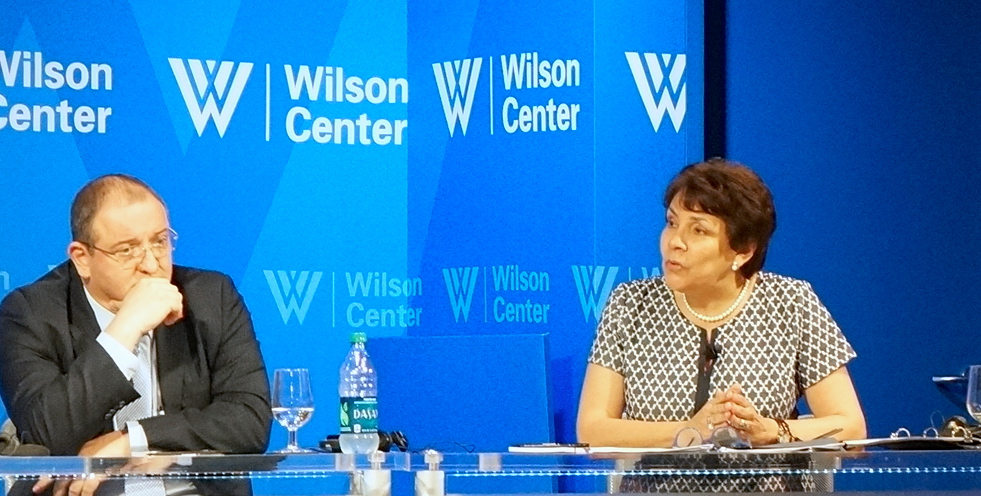

Like Hernández, Honduras’s foreign minister Mireya Agüero de Corrales (pictured above, right, with Guatemalan foreign minister Fernando Carrera) echoed the same points at a panel discussion at the Woodrow Wilson International Center last Thursday, noting that Honduras has become the chief transit countries for drugs originating in South America for North American destinations, thereby causing a ‘large international crime organization’ to be ‘installed’ in her country.

Hernández’s diagnosis also conveniently overlooks the nexus between US foreign policy and the corruption that epitomizes Honduran governance today, including the Hernández administration. Dana Frank, a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Cruz, has written eloquently about the factors linking US policy, the breakdown in Honduran security, and the 2009 coup and its aftermath.

Shortly after the 2009 coup, the conservative Partido Nacional (PN, National Party) won national elections under the candidacy of Porfirio Lobo Sosa, with the controversial blessing of the Obama administration. Though US officials were certainly relieved to see Honduran policy shift back in favor with the United States after drifting closer to the chavista left under Zelaya, human rights abuses increasingly worsened under the Lobo Sosa administration, the economy tanked and the homicide rate skyrocketed. Meanwhile, with US support, Hernández, who served as the powerful president of Honduras’s Congreso Nacional (National Congress) during the Lobo Sosa administration, pushed through a bill late last year establishing a new militarized police force, arguing during last autumn’s presidential campaign to do ‘whatever it takes’ to halt violent crime — even to the extent of downplaying human rights.

In particular, Frank argues convincingly that Hernández, far from elucidation the solution, is part of the problem of a corrupt country increasingly weakened by illegality over the past five years:

Hernández’s answer to police corruption, though, has been dangerous militarization. Not only does the regular military now patrol residential neighborhoods, airports, and prisons, but Hernández’s new 5,000-strong military police force is fanning out across the country… Worse, the police and military themselves kill and beat people with impunity….

Yet despite overwhelming evidence, the U.S. government continues to support, even celebrate the regime. Two days after the military police attacked the opposition members in congress, U.S. Ambassador Lisa Kubiske baldly praised President Hernández, lauded the TIGRES — a dangerous new special forces unit he has promoted–and said that the U.S. wants to invest “more and more in the Honduran police.” Commander John Kelley of the U.S. Southern Command, visiting Honduras on May 19, praised Hernández for his “impressive” and successful work against drug traffickers. Now, as a response to the influx of unaccompanied minors at the border, the White House has authorized $18.5 million in additional funds for the corrupt Honduran police.

Accordingly, when even the Honduran government can’t sort honest police from crooked police, US funds earmarked for fighting crime often end up purchasing weapons and otherwise supporting the exact violence that US funds are designed to thwart.

It’s not surprising that Hernández failed to mention his own country’s history of corruption, political and otherwise, in his laundry list of rationales for the current state of Honduran violence. After all, no one has benefitted more from the breakdown in the Honduran rule of law than Hernández and the ruling conservatives over the past five years (the president’s widespread nickname throughout Honduras is ‘Juan Robando’) — and that could increase exponentially if the Obama administration decide that the answer to the crisis of Honduran child migrants is to throw yet more military aid at the Honduran government.