HAVANA — On December 17, U.S. president Barack Obama announced that his administration would pursue executive policies designed to engage Cuba diplomatically and, potentially, restore relations between the two countries severed in 1960 – one year before Obama was born, as he himself noted in a joint conference with Cuban president Raúl Castro at the Summit of the Americas, the first time since the summits began in 1994 that a Cuban leader was invited to the affair.

It’s not only the White House that argues the 55-year embargo hasn’t worked – Republicans and Democrats alike, and Cubans, Americans and many others have long held that the embargo’s worst effects have fallen on the Cuban people, even as the policy gave Fidel Castro a convenient foil and excuse for the failures of his own government. No medicine? Blame the embargo, not the Revolution that guarantees universal health care to everyone. No food? Blame the embargo, not the abrupt end of Soviet subsidies, which plunged Cuba into what Castro euphemistically christened the “Special Period in a Time of Peace,” three years of hunger and deprivation where the average caloric intake dropped from around 3,000 calories per day to 1,400, according to some estimates. For all the initial promise of the Revolution, the reality fell far short for many Cubans, most especially for LGBT Cubans shuttled off to labor camps in the early 1970s and Afro-Cubans, who suffer from race-based income inequality decades after the Cuban government’s declaration that the Revolution “ended” racism. Even Fidel Castro admitted as much in a remarkable interview with Jeffrey Goldberg five years ago.

You don’t have to be a Nobel-winning economist, however, to realize that Cuba’s most recent financial benefactor, Venezuela, is going through some tough times. Two years after the death of leftist populist Hugo Chávez, oil prices are down and so is the level of production from PdVSA, the country’s state oil company. The official rate of the Venezuelan bolívar is comically lower than its market value, inflation runs rampant and shortages and rationing of basic foods and household goods is common. These days, everyday chavistas, who still hold faith in the socialist Bolivarian revolution, have taken to lobbing mangoes at Chávez’s successor, Nicolás Maduro, with messages desperately scrawled on them. Those less charitably inclined to Maduro, including opposition leader Leopoldo López and former Caracas mayor Antonio Ledezma, have been imprisoned. It’s dawning on the Castro regime that the days of exchanging Havana-trained doctors, Cuban intelligence agents and revolutionary slogans in exchange for cheap oil and other goodies may be coming to an end.

William LeoGrande, a professor at American University and the author of a new book on decades of back-channel negotiations between Havana and Washington, argues that the current round of negotiations isn’t the first time that U.S. and Cuban officials have sat down for talks, including the possibility of re-establishing diplomatic relations. This time around, the implosion of Venezuela, has refocused Cuban interest in reconciliation with the United States, which could provide Cuba the kind of tourist revenue and foreign development aid it desperately seeks.

“In one sense, Washington wants [normalization] more,” he said. “The United States was facing lots of diplomatic pressure from Latin America to change its policy towards Cuba. Now, the president has won a lot of credit, not just in Latin America, but around the world, for announcing his willingness to change policy. And it’s an important part of his foreign policy legacy, so I think the administration very much wants these negotiations to succeed.”

Privately, State Department officials agree that the Obama administration and the Castro regime are locked in a giant wager by launching a new era last December. The U.S. government is betting that a wave of liberalization and modernity will drag Cuba into the 21st century by empowering U.S. companies to do business directly with Cuban entrepreneurs, a step that will embolden individual freedom. The Cuban government is betting that it can liberalize à la carte by opening its economy, but not its politics, press or Internet, an approach that China and Vietnam have more-or-less successfully pursued.

News coverage since December paints a rosy, possibly naïve, tapestry of a partnership moving steadily forward. First were reports that Netflix would soon come to Cuba, something of a cruel joke for a country where Internet access is heavily restricted and censored, available for up to $10 an hour at designated government-run Internet cafes, universities and top tourist hotels. Then came AirBNB’s foray into Cuba, where homestays in casa particulares are a more popular option than overpriced hotels. JetBlue, earlier this year, announced grandiose plans to launch a commercial nonstop flight from New York to Havana by year’s end, followed this spring by hopes to re-establish a ferry service across the Straits of Florida between Key West and Havana. In March, Conan O’Brien hosted a virtual commercial for the faded glamour of a Caribbean playground filled with 1957 Plymouths, watered-down daiquiris and overpriced nights at the Tropicana. A high-profile delegation led by New York governor Andrew Cuomo and a group of state business leaders dropped in to talk about future opportunities. Havana is keenly anticipating a scheduled visit from Pope Francis in September, and there are promises of a possible stop by U.S. secretary of state John Kerry and even whispers that Obama himself might make a trip. A visit last month from French president Francois Hollande, the first Western European leader to visit the island since 1986, included an hour-long colloquy with Fidel Castro himself, though it also drew a critique from prolific blogger Yoani Sánchez when Hollande failed to meet any dissidents during his short trip.

Even in a best-case scenario, the Obama administration’s move could go awry simply because of the political gravity of presidential term limits. None of the nearly two dozen 2016 Republican presidential candidates, excepting Kentucky’s libertarian senator Rand Paul, supports the opening to Cuba. Two candidates, Senator Marco Rubio, himself the son of Cuban immigrants, and former governor Jeb Bush, come from Florida and swear fealty to the fiercely anti-Castro Cuban community in Miami. It’s true that, given the widespread cultural and economic interest among Americans in Cuba’s future, no Republican may be able to undo Obama’s work by the time January 2017 rolls around. In the fight to lift the embargo, the momentum is on Obama’s side, and many business interests, including the American farm lobby, are enthusiastic about accessing Cuban markets. But if the U.S. interests section in Havana is converted into a full embassy, a hawkish Republican in the Oval Office will have vastly greater leverage to undermine the Cuban regime in far more serious ways than broadcasting churlish messages from an electronic ticker or funding outlandish USAID programs to design fake Twitter programs like “ZunZuneo” (the latter ultimately backfired when its popularity crested, filling the coffers of the state-run mobile phone company).

Cuba, too, is set for its own political transition in 2018, when Raúl Castro has pledged to step down as president. For now, his likely successor is 54-year-old Miguel Díaz-Canel, appointed as first vice president in 2013. Alternate reports describe Díaz-Canel as either a hard-liner or a reformer, with varying strengths of ties to the Cuban military (though Díaz-Canel isn’t himself a military figure).

In short, few have credible insight into what Díaz-Canel truly believes, whether he’ll even make it to 2018 as the heir apparent and, if so, whether he’ll just be the civilian puppet that perpetuates the rule of the Cuban military. In the meanwhile, Raúl Castro has groomed his son, 49-year-old Alejandro, a rising figure within Cuba’s all-important MININT. Alejandro traveled with Raúl to the Summit of the Americas, lingering in the background in the photos where Raúl shook hands with Obama. Some Cubans believe that he will eventually emerge as the next Castro to rule the island. No one knows for sure, however, what the retirement of the elderly Castro brothers will mean for Cuba.

In the meanwhile, young Cubans are waiting for neither the Obama administration nor the Castro regime to deliver change to them. They’re getting on with making lives for themselves in a Cuba that, though still hampered by a heavy-handed state sector, provides more opportunities for them in decades. An informal poll of young Cubans on one weekend night in late May on the Malecón, the long walkway that rings the edge of Havana’s sea walls and where Cubans of every age and background flock on weekend nights, indicated that while Cuba’s youths are generally excited about closer ties with Americans, they don’t necessarily believe it will translate into better futures personally.

For those who believe that reform will not come soon enough, the United States continues to beckon. In the wake of Obama’s December announcement, the U.S. Coast Guard announced that a sharp uptick of Cubans took to boats in hopes of emigrating to the United States, fearing that reconciliation would mean the end of the favorable U.S. immigration policy towards Cubans. Under the current iteration of the U.S. Cuban Adjustment Act, the “wet foot, dry foot” policy extends a path to residency for any Cuban who makes it to American shores (though not to any Cubans caught by the Coast Guard en route to Florida).

In the 2012 film Una noche, a highlight of Cuban cinema in the past decade, NYU-trained Lucy Mulloy directed the neorealistic tale of three young Cubans who ultimately attempt to leave the country on a makeshift raft. Life imitated art when, a year later, two of the three co-stars, Anailín de la Rúa de la Torre and Javier Núñez Florián (pictured above), decided to stay in Miami en route to a film festival in New York. Though they play brother and sister in the film, they fell in love during filming and now live in Las Vegas with their young son.

Unlike the previous generations of Cuban emigrants to the United States, Núñez Florián wasn’t overly concerned about politics when I spoke to him last week. He said that he had always hoped to one day live in the United States and that his decision was about building a better future for himself and his family. He added that it’s not difficult to balance his life between the two worlds, that half his friends are still in Cuba, and that it’s easy for him to visit Cuba. Though he initially demurred when I asked him about the dynamics of US-Cuban relations, he agreed that he sees it in a positive light.

“Yes it’s good,” he said. “The U.S. is meeting in the middle, little by little getting closer to Cuba, and Cuba the same. Little by little everything is changing for the better.”

“Little by little,” though, is the key phrase. It’s easy to forget that, amid the excitement over Cuba’s opening, the Revolution took place only six years after the final armistice that divided North Korea and South Korea. Americans who believe that Cuba will suddenly be transformed, as if overnight, will be sorely disabused. Cuba’s modernization will be a difficult process that moves in zigs and zags.

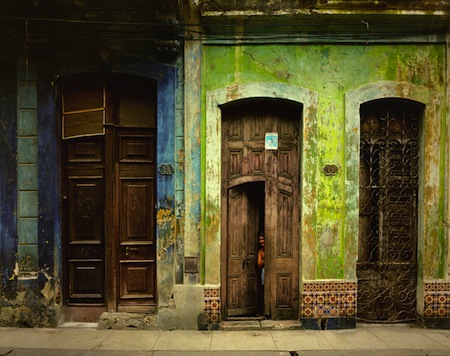

Former Bush-era commerce secretary Carlos Gutierrez, himself a Cuban-American, believes that Cuba can be a veritable Caribbean Singapore, but that’s hard to believe after a few days on the ground in Havana. The “romance” of 1950s jalopies subsides after a couple of taxi rides in an overcrowded Soviet-era Lada from the 1970s, and Havana suffers from all the other shocks of decades of economic mismanagement, exacerbated by U.S. stubbornness. On my first Friday night in Havana, I stopped at a bar for a little refreshment but by 10 p.m., it was out of shrimp, it was out of tostones (which I’d thought were ubiquitous throughout the region) and, the greatest sin of all, my waiter informed me that mojitos were no longer available. This wasn’t a flashy hotel or a secluded resort in the foreigners-only enclave of Varadero, but it was still a Chilean-themed bar directly across from the Malecón. From transportation to distribution networks, Cuba is woefully unprepared for a deluge of American tourists who won’t take kindly to surly rooms with Soviet air conditioners and bars that run out of mojitos.

Cubans may also find that competing for U.S. customers will be equally difficult. For years, cigar experts have warned that the Cuban tobacco-growing industry suffers from inconsistent quality control. The Havana Club brand, if it ever makes it into the American market given the copyright tangles with Bacardi, will face stiff competition from much smoother aged rums. After the post-taboo novelty of Cuban cigars and rum wear off, Millennial cognoscenti may find they prefer to sip on Guatemalan rum and smoke Nicaraguan cigars.

Meanwhile, Cuba’s infrastructure is broken. The Cold War never turned hot in Havana, but it did singe Nicaragua, Grenada and Panama City, where U.S. forces bombed the city’s charming Casco Viejo district in its ultimately successful 1989 push to arrest the drug-fueled strongman Manuel Noriega. Remarkably, large swaths of central Havana resemble Casco Viejo as it existed ten years ago, when it was still a bombed-out shell. Today, shopping boutiques and gelato shops adorn the Panamanian neighborhood, but central Havana continues to crumble. Buildings routinely fall to the ground in disrepair and floods in early May resulted in the deaths of at least three residents. Cuba’s currency system is also a mess, with the moneda nacional for Cubans and a fixed-rate convertible peso for tourists that’s created a two-tiered economy of have-nots and have-even-less. Neither currency is worth much internationally, and the Cuban government benefits from the privilege of collecting the hard currency of euros and dollars when tourists arrive to the island. Plans to merge the two currencies worry middle-class Cubans, chiefly in the tourism and hospitality industries, who fear that a botched attempt could wipe out the real gains of the past two decades.

It’s not an exaggeration to argue that the 1959 revolution both won Cuba its independence and conclusively ended the Monroe Doctrine, not only for Cuba but for all of Latin America. The relationship between the United States and Cuba has been troubled since the beginning. In 1854, U.S. president Franklin Pierce came close to annexing the island through the Ostend Manifesto proclaimed by Southern Democrats anxious to expand the geography of American slavery. Many Cubans believe the United States, by entering the Spanish-American War in 1898, stepped into a fight against a colonial Spanish force already chiefly defeated by Cuba patriots. For the next sixty years, under the Platt Amendment and a series of other measures designed to maximize American influence on the island, Cuba became a satellite of the U.S. government, with barely more de facto independence than Guam or Puerto Rico. If Cuba seems to have more in common with post-colonial African countries that won sovereignty in the late 1950s and 1960s, that’s because it suffered the same kind of post-independence growing pains under the penumbra of the Cold War.

“The U.S. has a history of meddling in Cuban affairs well before 1959,” said Arturo López-Levy, a Cuban-born scholar and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies. “In fact, this is in part what led to the Revolution. Cubans haven’t forgotten that. A normalization of relations doesn’t erase this history, and Cubans are weary of the United States opening an embassy and using it as a base to influence opposition groups.”

That, in part, explains why Americans don’t always understand that Che Guevara is such a hero to Latin America and the rest of the world, no matter how brutal his guerrilla techniques, and that when Fidel Castro dies, his name will be uttered in the same breath as the likes of Nelson Mandela. “Normalization” of U.S.-Cuban relations, as sought by the Obama administration, is really the promise that, for the first time, the United States will treat Cuba as a sovereign equal.

![]()