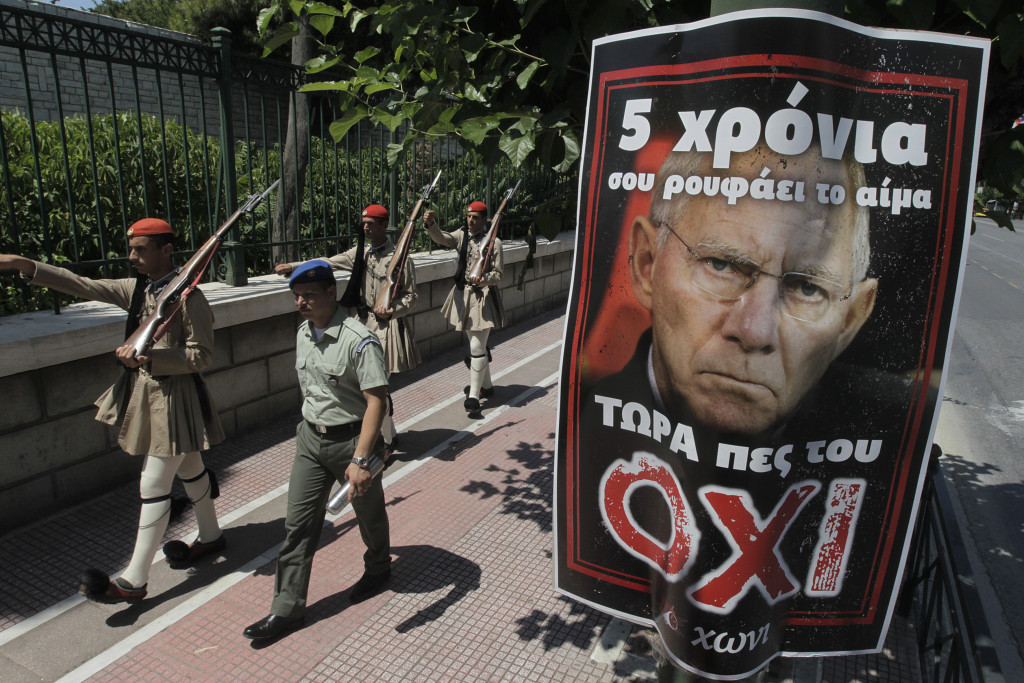

Photo credit to Angelos Tzortzinis /AFP.

Photo credit to Angelos Tzortzinis /AFP.

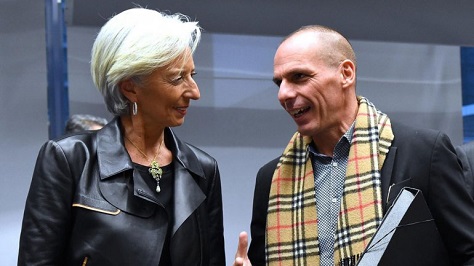

Though it’s Yanis Varoufakis, the Marxist economist and recently deposed Greek finance minister, who is typically painted in the media as the drag on the long-running negotiations to avoid a Greek default and keep the country within the eurozone, his intransigence has been met at every step of the way by Germany’s finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble, whose sneering impatience for Greek demands has been no less personal than Varoufakis’s over-the-top denunciations of European ministerial colleagues as ‘terrorists.’![]()

Schäuble’s sharp-tongued wit has been a constant through five years of negotiations that stretch back long before prime minister Alexis Tsipras and the far-left SYRIZA (Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς, the Coalition of the Radical Left) took power in January. On Thursday, Schäuble joked to an increasingly concerned US treasury secretary Jack Lew that he would be willing to swap Europe’s Greece troubles for Puerto Rico’s debt crisis.

When it comes to Greece, Schäuble is in many ways Germany’s opposition leader, even though he’s a stalwart of chancellor Angela Merkel’s governing Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party). He’s made it clear throughout the course of negotiations that he favors pushing Greece out of the eurozone, a result that other European leaders worry could destroy the single currency’s credibility — not to mention plunge Greece into an even more painful depression. Back in 2011 and 2012, few German politicians — just a handful of grey-haired Bavarian conservatives — were willing to call for Greece’s eurozone exit. Today, however, it’s a mainstream position, even on the center-left.

Germany is currently governed through a ‘grand coalition’ between the center-right CDU and the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) that includes around 80% of the entire Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament. Nevertheless, Merkel is limited in her maneuverability — if she gives too much to Greece, there’s a chance Schäuble could lead a revolt of CDU backbenchers who already worry Merkel has transformed the party into a political amoeba that sways to the path of political expediency.

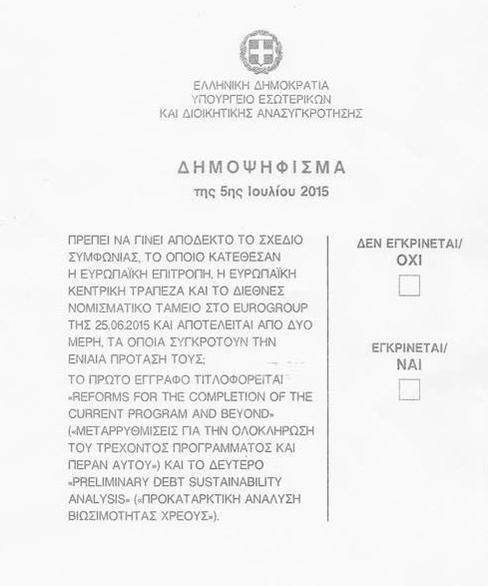

As Tsipras and his new finance minister Euclid Tsakalotos wait for Greece’s creditors to evaluation the government’s probable last proposal for debt relief, there’s a lot that lies in Schäuble’s hands. Even as French president François Hollande has directed his entire economic leadership — prime minister Manuel Valls, finance minister Michel Sapin and economic minister Emmanuel Macron — to help save Greece’s place in the eurozone, German doubts about the deal, a three-year bailout of over €50 billion, could still derail Saturday’s deadline. A full summit of the European Union’s leaders has been scheduled for Sunday. With banks running out of money and Greece banks nearing insolvency, European leaders have made it clear that if they don’t reach a deal with Tsipras on Saturday, they will spend Sunday addressing how Greece will exit the single currency.

Germany, as the largest member-state, is the largest contribution to any stability funding that comes from the European Commission and/or the European Central Bank. It’s currently on the hook for around €90 billion of Greece’s €5320 billion public debt. Merkel, despite doubts in her own party, has supported Greece’s two bailouts in the past, though she’s done so by demanding harsh strings that satisfy her own conservative flank and, of course, German taxpayers, who are ultimately on the hook for nearly one-third of Greece’s bailout debt.

Back in 2010, with a nod to moral hazard, Merkel cruelly told then-prime minister George Papandreou that she had to make the bailout as difficult as possible:

Mr. Papandreou says that when he asked German Chancellor Angela Merkel for gentler conditions in 2010, she replied that the aid program had to hurt. “We want to make sure nobody else will want this,” Ms. Merkel told him.

In principle, it was Merkel’s nod toward moral hazard — she couldn’t give the Greeks terms that Spain, Italy, Ireland, Portugal or the Baltic states might soon want. But in practice, it was a sop to the German right, which was growing ever more disgusted at consecutive Greek governments, which haven’t had the strongest reform record.

But Schäuble makes Merkel look relatively welcoming. The 72-year-old finance minister, according to reports, apparently asked Greek negotiators how much money it would take to get them to leave the eurozone. Continue reading How Schäuble’s failures shape the eurozone fight