Yesterday, Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission announced that, in light of technical glitches in its electronic system, it would instead proceed with a hand count of the results in Kenya’s presidential election and said that it would target a Friday announcement.

So no one expected a result on Thursday, but it was nonetheless a tense day.

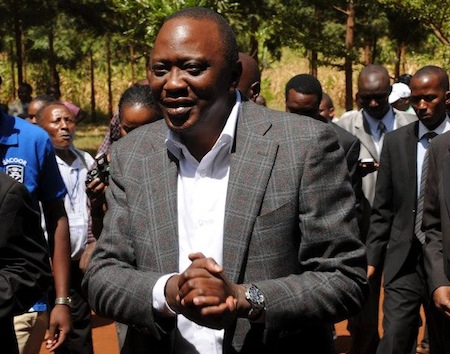

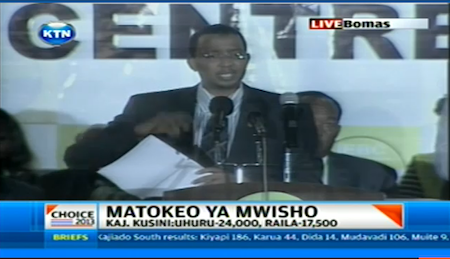

The revamped vote count continued to show a ever-narrowing contest between the Jubilee alliance candidate, former finance minister and deputy finance minister Uhuru Kenyatta, and the candidate of the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD), prime minister Raila Odinga (pictured above).

Kenyatta, who belongs to the Kikuyu ethnic group, is the son of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, and the runner-up in the 2002 presidential election to incumbent Mwai Kibaki.

Odinga, who belongs to the Luo ethnic group, is the son of Kenya’s first vice president and longtime opposition figure Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, and the runner-up in the very closely contested 2007 presidential election — the post-election tumult led to a power-sharing deal between Kibaki and Odinga, who has served as prime minister since 2008.

He escalated tensions earlier Thursday when he alleged that the IEBC was doctoring results and pulled his agents out of the vote-counting observation, though the IEBC firmly denied any unfairness or fraud in the counting of votes, even as it has admitted and acknowledged numerous glitches in the counting process.

Although Kenyatta has led consistently since the botched vote count began, that lead is narrowing as a fuller view of national results comes into relief — given the role of ethnicity in Kenyan politics, results vary widely by region. As of around 6:30 p.m. EST (2:30 a.m. on Friday morning, Nairobi time), with votes tallied in 170 constituencies out of 299 total, Kenyatta led with 3,705,316 votes (48.92%), with Odinga winning 3,422,275 votes (45.18%), deputy prime minister Musalia Mudavadi in third place with around 3.65% and ruined ballots totaling 0.997% of the total votes cast, much less than the 7% reported figure for spoiled ballots earlier this week (the IEBC has also blamed the electronic glitch for that).

If the margin remains this tight or tightens further, Kenyatta and Odinga will proceed to a runoff. A candidate will only win after Monday’s election with an absolute majority of over 50% of the total vote (including, according to the IEBC, all ruined ballots, a position that Kenyatta’s supporters challenged on Wednesday).

A runoff would make the third-place challenger Mudavadi, who belongs to the Luhya ethnic group, a likely kingmaker.

Mudavadi, ironically, served as both Kenyatta’s 2002 running mate and Odinga’s 2007 running mate. He’s the candidate of the Amani coalition, which includes his own Luhya-dominated political party as well as the Kenya African National Union (KANU), the longtime ruling party in Kenya until 2002, and which Uhuru Kenyatta led until 2012. Mudavadi’s backers in KANU, such as former president Daniel arap Moi and his son, KANU’s current leader, Gideon Moi, may want to broker a reunion with Kenyatta in advance of a second-round vote, many Luhya voters supported Odinga in the current round, supported him overwhelmingly in 2007 over Kibaki, and might naturally lean toward Odinga in a runoff.

Meanwhile on Thursday, the International Criminal Court, which has indicted both Kenyatta and his running mate William Ruto for their alleged role in the post-election violence in 2007 and 2008, pushed back a hearing on Kenyatta until July 9 as the prospect of a runoff between Kenyatta and Odinga became likely — a runoff scheduled to take place on April 11, the day after hearings were set to begin on Kenyatta. Kenyatta and Ruto, the latter from the Kalenjin ethnic group, were on opposite sides in 2007, and many Kenyans, including Odinga, have criticized their trial as an intrusion on Nairobi’s sovereignty. ICC prosecutors have also been criticized for assembling a relative weak evidential case against Kenyatta for any crimes against humanity.

Kenyans also elected new members to its National Assembly, the lower house of the Kenyan parliament, and for the first time, members to a newly-established upper house, the Senate, as well as governors and county assemblies for the 47 counties established under Kenya’s new constitution, which was adopted in 2010 and devolves significant power to county-level governments.

![]()

![]()