No matter who wins Israel’s election tomorrow, no party is expected to win more than a fragment of the seats necessary to win a majority in Israel’s unicameral 120-member parliament, the Knesset (הַכְּנֶסֶת).![]()

That means that for days and, likely, weeks after the voting ends, Israel will be caught up in the battle to form a new governing coalition. That process will begin as soon as Tuesday, when Israel’s president Reuven Rivlin begins talking to party leaders to assess who should have the first shot at forming a coalition.

That individual, whether it is current prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu or Labor Party leader Isaac Herzog, will then have 42 days to build a government that can win at least a 61-vote majority in the Knesset.

The bottom line is that Israel and the world could be waiting a long time for a new government, though Rivlin is said to be anxious to speed the process along. That, in part, will depend on Israel’s many parties.

Rivlin, previously the speaker of the Knesset and, until his presidential election last year, a member of the center-right Likud, will have some discretion in naming a prime ministerial candidate, but it will almost certainly be the leader whose party wins the most votes in Tuesday’s election (unless a clear majority of other party leaders, over the course of presidential talks, support the second-place winner to lead the next government).

So how to keep track of the various coalition possibilities?

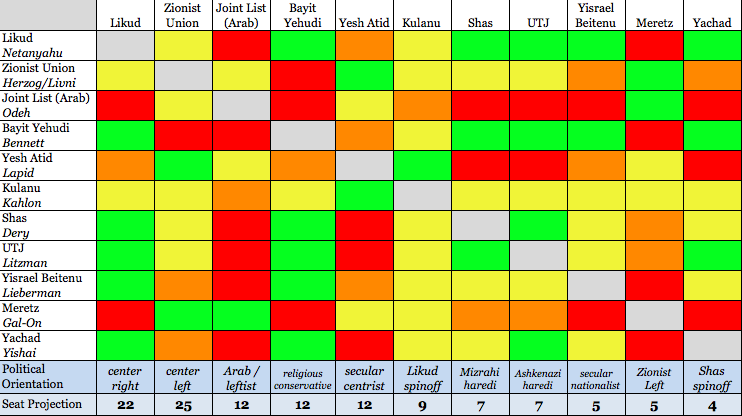

Suffragio‘s guide to the Israeli political parties and each party’s compatibility with every other party, as determined on a subjective scale of four degrees. Here’s what each of the colors mean:

Red. There’s absolutely no way the two parties would ever work together in a government. Not going to happen.

It’s impossible to imagine that Netanyahu would ever form a government supported by the Arab nationalist parties or Meretz, a Zionist left-wing party.

Former finance minister Yair Lapid, who demanded that Netanyahu exclude the ultraorthodox haredi parties from government in 2013, spent much of the campaign savaging Shas’s leader Arye Dery as something of a corrupt and racist felon. So it’s hard to imagine Lapid would cozy up to him in government.

Orange. It’s very unlikely the two parties would ever work together in coalition. But in Israeli politics, where your enemy today is your friend tomorrow, Knesset politics makes for some odd bedfellows.

While Netanyahu’s exasperation with Lapid is one of the proximate causes of snap elections, it’s not entirely out of the question that Lapid’s party, Yesh Atid, would find its way into a broad-based coalition with Netanyahu again — for the right price.

It’s equally hard to believe that Herzog and his centrist allies in the Zionist Union would join forces with foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman, the leader of the stridently nationalist Yisrael Beitenu, which ran in 2013 in electoral coalition with Likud. But Lieberman’s party stands to lose many of its seats, and he might find an alliance of convenience the best way to remain relevant in a post-Netanyahu environment.

Yellow. The two parties are not exactly natural allies, but the possibility to work together definitely exist under the right conditions (and, perhaps, with an offer of ministerial posts).

Kulanu, the party of former communications minister Moshe Kahlon, embodies this category. Although it’s a right-wing party that includes many former Likud figures, including Michael Oren, former Israeli ambassador to the United States, it could neatly fit as a junior partner with either Likud or the Zionist Union. For that reason, almost everyone believes Kahlon is a frontrunner to be the next finance minister.

On the same token, however, Rivlin and others are said to favor a national unity government between the Zionist Union and Likud. It’s happened before — as recently as 2011, Labor and Likud were united in the same government. The late prime minister Ariel Sharon, in forming the centrist Kadima party in 2005, brought together Likudniks and Laborites, including former president Shimon Peres.

Though the Joint List, the united Arab coalition, is unlikely to enter government formally, its leaders seem inclined to support Herzog from outside government.

Green. The two parties are closely allied on either the religious or ideological spectrum, and it is natural to expect that they would work together in any government.

Many of these allies are already committed to supporting a joint prime ministerial candidate.

Shas and United Torah Judaism, as the two longstanding haredi parties, the former appealing to Sephardic/Mizrahi Jews and the latter to Ashkenazi Jews, often find common ground.

So would Meretz and the Zionist Union, even though they’re competing for support from the same pool of left-minded voters.

The same dynamic exists for Likud and Naftali Bennett’s Bayit Yehudi, a more conservative, pro-settler party of the Israeli right.

Seat predictions come from the indispensable Knesset Jeremy.

* * * * *

In the meanwhile, if you’re hungry for more analysis, see below all of Suffragio‘s coverage of Israel’s 2015 election:

Palestine comes to the fore on Israeli election eve

March 16, 2015

Israel’s split haredi parties still hope to hold balance of power

March 15, 2015

Israeli Arabs unite with fresh voice for non-Jewish voters

March 12, 2015

Who is Isaac Herzog? A look at Israel’s opposition leader

March 3, 2015

The real reason Netanyahu is coming to Washington

January 28, 2015

Netanyahu sacks Lapid, Livni; seeks snap 2015 elections

December 3, 2014

Top Netanyahu rival leaves politics — for now

October 7, 2014

Read all of Suffragio‘s coverage of the 2013 Israel election here.