That Israel’s hard-line foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman will resign following indictments Thursday for breach of trust doesn’t mean he’s leaving politics.

![]()

To the contrary, Lieberman’s move seems calculated to allow him to return to the forefront of Israel’s coalition government, headed by Benjamin Netanyahu, upon the strong likelihood that Netanyahu emerges from upcoming elections as prime minister. Given that Israel’s essentially in campaign season, Lieberman (pictured above) is moving aggressively — and wisely, probably — to lift his parliamentary immunity in order to bring investigations to resolution as fast as possible about the charges that remain.

Those charges, by the way, are only derivative of the main charges against Lieberman that stem from a 12-year investigation with respect to money laundering and fraud — Lieberman stood accused of receiving millions from international businessmen while he was serving in office. Israel’s attorney general Yehuda Weinstein determined not to pursue charges against him on those accusations. The remaining charge is that Lieberman breached public trust by appointing Ze’ev Ben Aryeh as ambassador to Belarus without disclosing that Ben Aryeh had alerted Lieberman that he was being investigated by Belorussian authorities. So all things considered, Thursday was somewhat of a victory for Lieberman in that it lifted a decade-long shadow from his public life.

Netanyahu is holding Lieberman’s portfolio ‘in trust’ and will serve simultaneously as prime minister and foreign minister until the January 22 elections for the Knesset (הכנסת), Israel’s 120-seat unicameral parliament.

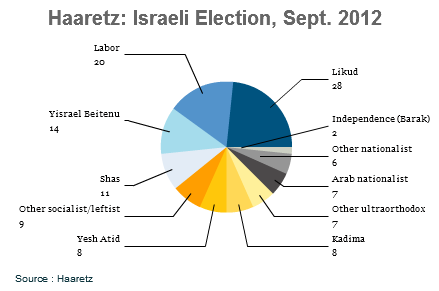

In advance of the election, Netanyahu had teamed up with Lieberman to merge Israel’s longstanding center-right party Likud (הַלִּכּוּד, ‘The Consolidation’) with Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu (ישראל ביתנו, ‘Israel is Our Home’). At the last election, Yisrael Beiteinu, with a strongly nationalist secular profile that appeals to many of Israel’s ethnic Russian Jewish population, won 15 seats to 27 for Likud, and 28 for the more centrist — and now-imploding — Kadima (קדימה, Forward). The coalition between Netanyahu and Lieberman has remained the core of Israel’s government since 2009, and their combined ‘Likud Beiteinu’ ticket ensures that Lieberman and his allies will take at least 15 seats if the coalition retains its combined 42 Knesset seats.

The news threatens to sidetrack Lieberman less than a month after Netanyahu’s defense minister and former prime minister Ehud Barak said he wouldn’t stand for election in the Knesset, just two years after leaving Israel’s longstanding center-left party, Labor (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית) to found his own breakaway party, ‘Independence’ (סיעת העצמאות). Netanyahu could still, however, re-appoint Barak as a non-MK defense minister after the election.

But despite the conventional wisdom that Netanyahu will easily glide to reelection, things are looking decidedly less secure for him in the wake of a number of disappointments for his government — Netanyahu was widely seen to have publicly challenged U.S. president Barack Obama over Iran and also to have favored Republican candidate Mitt Romney in the U.S. presidential election, so Obama’s reelection was widely seen as a setback for Netanyahu.

Furthermore, the eight-day bombing campaign in Gaza in November, the United Nations vote on Nov. 30 to recognize Palestine as a non-member observer state and the Israeli announcement of further settlements in the West Bank have called into question Netanyahu’s sincerity on achieving Israeli-Palestinian peace, but his diplomatic abilities as well, given Israel’s increasingly negative image in the world. Those defeats came after Netanyahu’s cartoonish Cassandra siren demanding ‘red lines’ with regard to Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program.

Those troubles are borne out in a poll released today — conducted before Lieberman’s resignation — that finds ‘Likud Beiteinu’ would win just 37 seats in the election, a bit of a retreat from their current 42 seats. In the poll, 54% of Israeli voters say that Israel’s diplomatic position has gotten worse in the past four years, at a time when Israeli diplomacy will remain vital throughout the Middle East in 2013 and beyond — on Egypt, on Palestine, on Syria and Lebanon and on Iran.

But Likud Beiteinu’s loss — so far — has not meant a gain for the forces of Israel’s horribly fractured center-left. Instead, the even more stridently Zionist, conservative Bayit Yehudi (הבית היהודי, ‘The Jewish Home’) would win 16 seats, up from just three in the current Knesset.

That party — or rather coalition of parties — is led by Naftali Bennett, who served as Netanyahu’s chief of staff in opposition from 2006 to 2008, and it has been a component, albeit a small component, of Netanyahu’s coalition, and could be expected to join future Netanyahu-led coalitions as well. Bennett is rapidly becoming a rising star in Israel, and he’ll be headed for a major cabinet post if he places third — or higher — in January’s elections. Bennett, born to American parents and a former New York City resident, founded and sold a company in his 20s to become independently wealthy before returning to Israel, serving in the Israeli Defense Force during the short-lived 2006 war in Lebanon and then in politics as Netanyahu’s chief of staff.

For now, then, while Lieberman’s troubles could result in harming Lieberman’s reputation, it shouldn’t affect Netanyahu’s position to remain prime minister — though a stronger Jewish Home bloc in the Knesset would arguably make a future Netanyahu government more Zionist in nature and less secular.

The poll showed that the center-left, currently fragmented among three major groups, would win just 36 seats total, meaning that, even if a world where the three parties could unite somehow, they still don’t command enough support to form a government: Continue reading Lieberman resignation complicates Netanyahu coalition’s election chances