No issue looms larger in Iran’s foreign relations than its nuclear program and global fears that Iran’s nuclear energy program could quickly transform into a nuclear weapons program.

So it was with some sadness last month that one of the pioneers of international relations theory, Kenneth Waltz died just days before the Iranian election, which the entire world is watching in large part for its implications for Iran’s nuclear program.

Waltz, a founder of the realist school of international relations, may perhaps have been most well-known in recent years for his argument that we should welcome nuclear proliferation because nation-states act more responsibly with nuclear arms than without them. So even assuming the worst intentions of Iran’s nuclear program — that it’s not only pursuing nuclear energy, but it’s also clandestinely developing a breakout capability to build a nuclear weapon — the West should not be so concerned with Iran’s nuclear machinations. Moreover, it should embrace Iran’s entry into the nuclear club, as Waltz himself argued in Foreign Affairs last summer:

History shows that when countries acquire the bomb, they feel increasingly vulnerable and become acutely aware that their nuclear weapons make them a potential target in the eyes of major powers. This awareness discourages nuclear states from bold and aggressive action. Maoist China, for example, became much less bellicose after acquiring nuclear weapons in 1964, and India and Pakistan have both become more cautious since going nuclear. There is little reason to believe Iran would break this mold.

As you might realize, this is a controversial position, and others have argued that Waltz’s views are irresponsible and short-sighted, though I’ve always found that Waltz’s reasoning on nuclear weapons makes a lot of sense. For many reasons, however, no one should expect that the United States will follow Waltz’s advice anytime soon.

Moreover, it’s worth noting very clearly that Iran is not necessarily seeking to develop nuclear weapons, but rather simply an alternative energy program. That would enable the Islamic Republic to export more of its copious fossil fuels, and it’s a goal that U.S. policymakers actually nurtured in the 1950s, 1960 and 1970s during the rule of Iran’s shah, who was deposed in the 1979 revolution that led to the establishment of the Islamic Republic. As Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett note in their new book on U.S.-Iranian relations, Going to Tehran: Why the United States Must Come to Terms with the Islamic Republic of Iran (which is a very compelling read, even if Roger Cohen and much of the official Washington commentariat have written it off as apology for the Iranian regime), a nuclear weapons program is unlawful under Islamic law, a constraint that the Leveretts argue is ‘more substantial than most Western analysts appreciate’:

Ahmadinejad has described nuclear weapons as a ‘fire against humanity,’ charging that ‘to have a nuclear bomb is not only a dishonor; it’s obscene and shameful. Threatening to use it and using it is even more shameful.’… As recently as 2012, [Supreme Leader Ali] Khamenei reiterated his stance that, from an ideological and fiqhi [Islamic jurisprudence] perspective, we consider developing nuclear weapons as unlawful. We consider using such weapons as a big sin.’

Even if you aren’t as sanguine as the Leveretts that Iran’s leaders are not pursuing nuclear weapons, that doesn’t matter under Waltz’s analysis, because he’s argued that it’s in Iran’s national interest to pursue at least the capability of nuclear weaponry in light of Israel’s longstanding (though unofficial) nuclear capability:

Israel’s regional nuclear monopoly, which has proved remarkably durable for the past four decades, has long fueled instability in the Middle East. In no other region of the world does a lone, unchecked nuclear state exist. It is Israel’s nuclear arsenal, not Iran’s desire for one, that has contributed most to the current crisis. Power, after all, begs to be balanced. What is surprising about the Israeli case is that it has taken so long for a potential balancer to emerge.

Waltz, like the Leveretts, have argued that the West, generally, and the United States, specifically, have systemically assumed that Iran’s Islamic leadership means it will not respond to the typical deterrents that constrain nuclear-armed nation-states and that Iran will not act rationally in its national interest if it acquires a nuclear weapon. But despite Iranian support for Hezbollah and other groups that have at times wreaked major havoc throughout the Middle East, there’s really no tangible support for that view of Iran, which has conducted a foreign policy over the past 30 years that’s been more defensive than offensive. It was an U.S.-backed Iraq, after all, that launched an invasion of Iran shortly after the revolution. Even in light of often heated and inappropriate rhetoric against Israel’s right to exist, Iran has never launched a full-frontal military attack on Israel, despite some evidence that Israel has helped assassinate several of Iran’s top nuclear scientists and its demonstrated willingness in the past 30 years to launch preemptive strikes against other Middle Eastern states, including Iraq and Syria.

As Waltz wrote:

Despite a widespread belief to the contrary, Iranian policy is made not by “mad mullahs” but by perfectly sane ayatollahs who want to survive just like any other leaders. Although Iran’s leaders indulge in inflammatory and hateful rhetoric, they show no propensity for self-destruction. It would be a grave error for policymakers in the United States and Israel to assume otherwise.

Yet that is precisely what many U.S. and Israeli officials and analysts have done. Portraying Iran as irrational has allowed them to argue that the logic of nuclear deterrence does not apply to the Islamic Republic. If Iran acquired a nuclear weapon, they warn, it would not hesitate to use it in a first strike against Israel, even though doing so would invite massive retaliation and risk destroying everything the Iranian regime holds dear.

The biggest criticism against Waltz is that he too breezily dismisses otherwise valid concerns that nuclear weapons could fall into the hands of more radical terrorist groups or other non-state actors. But it seems unlikely that Iran would hand over nukes to Hezbollah or Hamas or anyone other related groups because any such nuclear attack would invariably be linked to Iran, even if Iran didn’t turn out to be the ultimate source. (Let’s keep in mind that U.S. intelligence couldn’t tell the difference in 2002 the difference between a genuine nuclear program in Iraq and Saddam Hussein’s bluffing to make Iran think he had weapons of mass destruction). Furthermore, the risk of ‘loose nukes’ seems even greater in the context of the former Soviet Union or, more forebodingly, Pakistan, whose civilian government and military do not even exert territorial dominance throughout the entire country.

No one seriously believes that U.S. negotiators are simply going to relent to Iran’s nuclear energy program so long as it could facilitate the building of an Iranian nuclear weapon, though. Talks have stalled throughout Ahmadinejad’s second term over the issue of whether Iran will allow its uranium to be enriched abroad, and while the chance of a military encounter between Iran and the United States remains relatively low, it’s not wholly out of the realm of possibility, and an Israeli strike against Iran could quickly escalate.

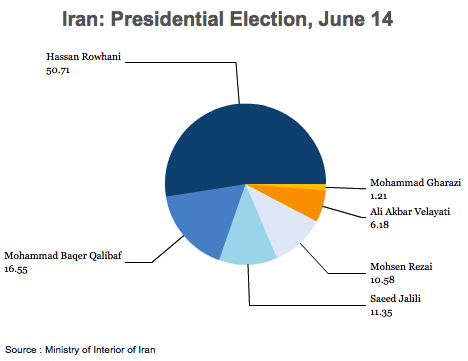

But Iran’s presidential election could provide a way for the United States and its allies, on the one hand, and Iran, on the other hand, to mark a pivot point from the current impasse in two regards. First, the next Iranian president could be much more open to conciliation than Ahmadinejad ever was. Second, with the election firmly in the past, the occasion of a new president could be an opportunity for renewal of negotiations, regardless of the election’s winner. Continue reading How the West could learn to stop worrying and love a nuclear Iran →