No one has accused Brazil’s president, Dilma Rousseff, of any personal impropriety in the sweeping investigations of kickbacks to politicians in Brazil from the state oil company, Petrobras.![]()

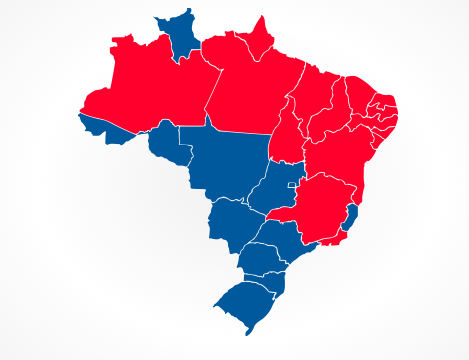

Nevertheless, a two-thirds majority of the Câmara dos Deputados (Chamber of Deputies) decided to impeach Rousseff anyway, based on an obscure theory — that Rousseff fudged the budget numbers in the lead-up to the 2014 election to hide the precarious condition of Brazil’s budget deficit and reduce the need to cut spending in an election year.

No one had any doubts in 2014 that the country’s increasing debt burden was weighing down its economic outlook and even Rousseff, after her reelection, shook up her cabinet, bringing in Joaquim Levy as finance minister, and Nelson Barbosa, now Levy’s successor, to introduce greater budget discipline as the country sinks further into recession.

* * * * *

RELATED: Collor faced Brazilian impeachment crucible

25 years before Dilma

* * * * *

In reality, it’s the Petrobras scandal that’s swept up Rousseff, along with nearly 320 members of the Brazilian congress. Operation Car Wash has uncovered a wide-ranging scheme whereby leading politicians accepted kickbacks on the basis of inflated public contracts granted from Petrobras. The scandal implicates Rousseff’s own Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT, Workers Party), but it has also snared politicians from across the ideological spectrum. The scandal took an even sharper turn this spring when former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Rousseff’s mentor who first won power in 2002, was also accused of taking kickbacks. The speaker of the Chamber of Deputies, Eduardo Cunha, among many, many others, are also under investigation. Brazilians refer to the scandal as the petrolão, which translates to the ‘big oily.’

The battle moves to Brazil’s Senate

Complicating the impeachment vote is the fact that Rousseff herself is personally and politically unpopular. A collapsing economy has left her with an approval rating in the teens. In one sense, Rousseff was impeached on Sunday because she’s so widely reviled by Brazilians. Rousseff’s opponents, even though many of them are under investigation themselves, blatantly admit that they supported impeachment just to remove her from office for political reasons. The Brazilian right has lost four consecutive elections to either Lula or to Rousseff, though Rousseff only narrowly won reelection in October 2014.

The nakedly political considerations involved explain why Rousseff and her left-leaning supporters have been quick to label the impeachment vote as an undemocratic coup. But it’s more complicated than either side would like to admit. Rousseff is correct when she argues that the Brazilian media is, largely, anti-PT, and the business elite has increasingly turned against her and Lula.

But Rousseff herself served as the chairwoman of the Petrobras board between 2003 and 2010, and her critics believe it’s risible that she knew nothing about the kickbacks. Moreover, she blatantly attempted to appoint Lula to her cabinet last month as a way of offering him immunity from prosecution. (Rousseff’s supporters subsequently attacked the lead prosecutor, Sérgio Moro, for releasing the audio recording of a conversation between Lula and Rousseff).

Rousseff is now almost certain to face a prolonged trial before the upper house of the Brazilian Congress. With just a majority vote in the 81-member Senado (Senate), she can be suspended for office for 180 days. Her vice president, Michel Temer, the 75-year-old leader of the Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (PMDB, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party), will almost certainly take over temporarily and, if not impeached himself, will take over if Rousseff is formally removed. The next elections are scheduled for 2018.

Temer and the PMDB broke with Rousseff earlier this month, in a step that now seems likely to have doomed Rousseff’s fate. Temer has already indicated that, as Brazil’s new president, he will pursue a much more center-right orientation that will look to assure markets and business elites. He has also indicated that he might attempt to rein in the Petrobras investigations that have thoroughly discredited a country’s worth of institutions. The PMDB is a ‘big tent’ party whose sole ideology seems to be proximity to power — it has provided support to every sitting Brazilian government, of the center-right or the center-left, since 1994. Temer, Cunha and other leading pemedebistas are under the same clouds of corruption as many of the leading petistas, so a Temer presidency would not wipe the political slate clean.

Rousseff will, however, survive if she can muster more than one-third of Brazil’s senators in a trial that might not begin until May.

Her removal isn’t a fait accompli.

Note, however, that Rousseff (and Temer, as her 2014 running mate) still faces the possibility that her reelection will be vacated by Brazil’s supreme electoral court, which is reviewing whether the Rousseff campaign received illegal campaign funds. If the court decides to vacate the election, Cunha (the scandal-plagued speaker of the Chamber of Deputies) will temporarily replace Temer as president before a fresh presidential vote later this year.

Brazil’s hyper-partisan future looks grim

Even if Rousseff survives the Senate trial, she will have virtually no power as a wildly unpopular lame-duck president — just the second in modern Brazilian democracy to be impeached. Rousseff will continue fighting to protect the legacy of lulismo and the PT’s four terms in power, most notably the massive programs that have reduced extreme poverty and inequality that have made Lula, Rousseff and the PT extremely popular among Brazil’s poor. Moreover, even as Lula himself faces criminal liability for his own possible role in the Petrobras scandal, he remains extremely popular in Brazil (much more so than Rousseff) and on the Latin American left, generally.

Indeed, if an election were held today, Lula would be competitive to win, as incredible as it seems. He’s essentially tied with the other top-tier contenders from the 2014 election, Marina Silva (an alternative leftist with socially conservative positions on abortion of LGBT rights and with roots in Brazil’s green movement) and Aécio Neves, a Brazilian senator and the former two-term governor of the state of Minas Gerais. Neves today is the leader of Brazil’s main center-right opposition party, the Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (PSDB, Brazilian Social Democracy Party), which has long supported Rousseff’s removal.

But the impeachment process and its aftermath are already making Brazil’s hyperpartisan divide even worse. A small glimpse of the ugliness came on the floor of the Chamber of Deputies Sunday night when one member, Jair Bolsonaro, who also hopes to run for president in 2018, dedicated his vote in favor of impeachment to the leader of a torture unit during Brazil’s military dictatorship whose victims included, among others, Rousseff herself. Other far-right deputies also voiced praise Sunday night for some of the leaders of Brazil’s military dictatorship from 1964 through 1985.

Though a majority of Brazilians (including both wealthy and poor Brazilians) supported Rousseff’s impeachment, the battle has left many voters divided sharply. Moreover, a compromised Temer-led interim presidency also seems unlikely to unite a country that still faces incredible challenges, including a nasty economic downturn, the rising threat of the Zika virus and the difficulty of hosting the first Summer Olympics in South American history later in 2016.

Brazil’s democracy has already survived one impeachment, when former president Fernando Collor resigned a day before the Brazilian senate voted formally to remove him from office in December 1992. But Collor, at the time, was more personally and, potentially, criminally implicated in the corruption scandal that spurred his impeachment, which the Chamber of Deputies passed in a near-unanimous vote. In contrast, the impeachment battle against Rousseff has been far more colored by partisan opinion.