There’s apparently a limit on what Ukraine’s president can get away with.

He could preside over massive amounts of corruption, he could jail his chief political opponent on ridiculously politicized charges, he could swerve disastrously between a pro-Russian worldview and a pro-European worldview, and he could even brazenly change Ukraine’s election law to win more seats.

But when the government of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych became responsible for the deaths of 88 protesters last week, even members within his own Party of Regions (Партія регіонів) were defecting from Yanukovych. Arguably, until his police force unleashed lethal fire on hundreds of civilians, Yanukovych could point to a relatively legitimate electoral mandate in the previous 2010 presidential election (and, though it was flawed, the 2012 parliamentary elections).

Since Friday, when the European Union seemed to broker a deal between Yanukovych and Ukraine’s opposition leaders, events galloped at a dramatically rapid rate (though apparently not too fast for Ukraine’s leading oligarchs, Rinat Akhmetov and Dmitry Firtash), leaving Yanukovych in hiding in eastern Ukraine, under charges of mass murder. The country’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, voted in quick succession to elect speaker Oleksander Turchinov (pictured above), an opposition, pro-European politician, as interim president.

It also elected to restore the 2004 constitution, which restores more power to Ukraine’s parliament and away from its president, and set a tentative May 25 date for new presidential elections. The parliament also cleared the path to free Yulia Tymoshenko, a former prime minister and a leader of the center-right ‘All Ukrainian Union — Fatherland’ party (Всеукраїнське об’єднання “Батьківщина), who narrowly lost the 2010 presidential vote to Yanukovych. Tymoshenko (pictured below) was jailed in late 2011 by Yanukovych’s government on charges related to her handling of the natural gas crisis in 2009 during her premiership. That precedent, ironically, may be one of the reasons that Yanukovych remained so keen on holding onto power in Kiev — having established that he was willing to throw Tymoshenko in prison on politically motivated grounds, it’s Yanukovych who now faces imprisonment on the basis of far more serious charges. Tymoshenko, who has ruled out leading Ukraine’s soon-to-be-announced interim government, will nonetheless be a leading candidate in the upcoming presidential ballot. Though she’s been imprisoned throughout the current crisis, she’s also unsullied by having negotiated with Yanukovych, a group that includes another opposition favorite, heavyweight boxing champion Vitaliy Klychko.

Russia, who had delivered $3 billion of a promised $15 billion bailout, is obviously dismayed. Though Yanukovych was never quite the Russian puppet that some Western leaders believed him to be, it’s clear that his sympathies lied to the east more than to the west.

So what comes next for Ukraine? Past experience demonstrates that the story won’t end with ‘happily ever after’ upon the appointment of this week’s new interim government. As I wrote last December, the Maidan protests — even if they succeed — won’t by themselves end Ukraine’s political crisis. Just a year after the ‘Orange Revolution’ of December 2004 and January 2005 that brought Viktor Yushchenko power, the pro-European government crumbled into infighting that lasted until Yushchenko left power, massively unpopular, in 2010. Yanukovych took advantage of the ongoing disunity of the Ukrainian opposition in October 2012’s parliamentary elections, winning largely by dividing the supporters of Tymoshenko’s Fatherland and Klychko’s newly formed Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform (Український демократичний альянс за реформи).

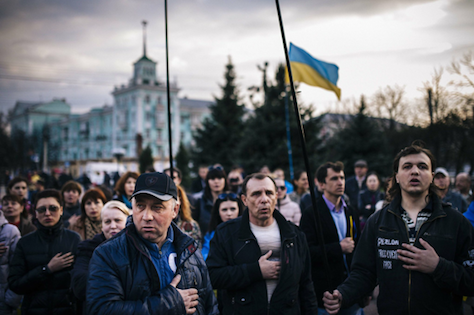

Almost on schedule, this morning brings news of serious counter-protests in Crimea, the peninsula that lies in the Black Sea on the southeastern coast, one of the 24 oblasts that comprise Ukraine. Continue reading What comes next for Ukraine following Yanukovych’s ouster? →

![]()