You’d be excused if you thought that Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd’s concession speech earlier today sounded more like the victory speech of a man who had just won the election.![]()

In a sense, Rudd did win the battle against expectations — just barely. Even though Rudd will soon become a former prime minister and has already announced he will step down as the leader of the center-left Australian Labor Party, he can breathe a sigh of relief that Labor did not fare as poorly as some worst-case scenarios projected — either under Rudd’s return to the leadership or under former prime minister Julia Gillard. So Rudd was probably right to gloat in his speech that he preserved Labor as a ‘viable fighting force for the future.’ What Rudd didn’t have to say was his belief that Gillard would have led Labor to an absolute collapse.

With three seats left to be determined, the center-right Coalition government led by Liberal Party leader Tony Abbott has 91 seats in Australia’s 150-member House of Representatives to just 54 seats for Labor and two independents, with Adam Bandt, the sole MP of the Australian Greens, holding onto his Melbourne seat despite a strong Labor push. That’s a very strong victory for Abbott, who has picked up 18 seats, but it’s not a historic landslide — four of those gains come from seats formerly held by independents.

Rudd, on the other hand, can claim that his three-month leadership of the party helped avert a catastrophe, though we’ll never know whether Gillard would have done better or worse (and there are some reasons to believe that Labor should have simply stuck with Gillard through September).

You can get all of the seat-by-seat results here, and you can read the pre-election analysis of the marginal seats here.

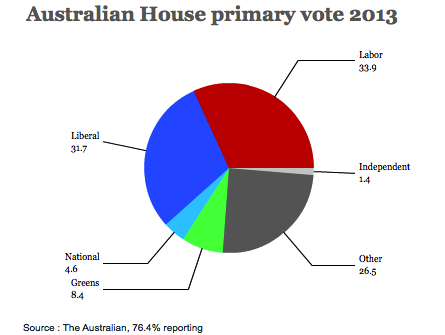

Here’s the result of the primary vote count:

The most striking piece is that more than one of every four voters chose as their first preference someone other than a Labor, Coalition or Green candidate, and it corroborates that the election was more a statement of disapproval of the Rudd-Gillard governments than an embrace of Tony Abbott.

So what comes next? Within a week, Abbott will likely become Australia’s new prime minister. What does that mean for Australian politics?

Abbott’s ambitious agenda may be difficult if the Coalition doesn’t win a Senate majority

Abbott drew a sharp contrast with Rudd during the campaign, so look for him to push forward with an ambitious policy agenda and to take an aggressive posture from day one:

- an attempt to repeal the carbon pricing scheme that Labor brought into effect in July 2012;

- an attempt to repeal the mining ‘superprofits’ tax that Gillard passed last year;

- the continuity of some form of the ‘Pacific solution’ for asylum seekers that former prime minister John Howard initiated (i.e., diverting migrant boats to Nauru and Papua New Guinea) and that Rudd recently embraced in a policy reversal;

- spending cuts to bring the Australian budget back into surplus after a 2% deficit this year (though don’t hold your breath waiting for a massive austerity program for the relatively low-debt Australian treasury); and

- the implementation of a fully funded, fully paid 26 weeks of paid parental leave.

Generally, you can look to Abbott to play marginally rougher with the Chinese and Australia’s other Asian neighbors and to embrace Australia’s strategic relationship with the United States with marginally more enthusiasm. Though Abbott is more socially conservative than Howard or former prime minister Malcolm Fraser, don’t expect him to push forward with massive anti-abortion regulation, but forget about same-sex marriage anytime in the next three years.

One of the biggest questions coming out of today’s results is whether Abbott will command a majority in the Senate. Going into the election, the Coalition held 34 out of 76 seats, but it’s an open question as to whether the balance of power will shift decisively in Abbott’s favor, due to the nature of Senate elections — only about one-half of the Senate is elected in a normal election, and huge swings are not typical. That means that Labor and the Greens might actually be in a position to veto Abbott’s agenda from the Senate for the next three years. But even if the Coalition narrowly wins a majority after all the votes are tallied, or can build an alliance with a handful of independents, it will be such a narrow margin that Abbott may find it difficult to pass his agenda through the upper house, especially his plan to repeal the carbon pricing scheme.

The key players in the Abbott government

Also expect Abbott’s cabinet to shape up pretty quickly in the next 36 hours. He is likely to appoint Joe Hockey (pictured top, left, alongside Abbott), a Sydney MP who is the leader of the Liberal Party’s moderate faction, as Australia’s next treasurer. He’s likely be joined by Victoria MP Andrew Robb, also more moderate than Abbott as finance minister in the task of cutting A$42 billion from the Australian budget. Julie Bishop, a Perth MP who is also the deputy leader of the Liberal Party, is expected to take up the foreign affairs portfolio, and she’s known for especially moderate views on asylum policy.

National Party leader Warren Truss, a social conservative likely to remain out of Abbott’s spotlight, is likely to become deputy prime minister with the infrastructure and transport portfolio.

Victoria MP Greg Hunt is currently shadow secretary for climate action and the environment, but he’s also a moderate (and he might not enjoy spending his first years as a minister dismantling the carbon trading markets). Likewise, former industry minister Ian Macfarlane is likely to become Abbott’s energy minister, even though he supported the carbon scheme when Malcolm Turnbull was the Liberal leader between 2008 and 2009. Turnbull himself is currently shadow minister for communications and broadband — Abbott supports Labor’s initiative to introduce nationwide broadband, but hopes to cut the project’s cost. South Australia MP Christopher Pyne, another moderate rising star, is likely to become education minister.

Shorten as Labor’s new leader?

But Labor has some important decisions to make in the coming days as well as it prepares to return to opposition. The most important decision is who it will elect as its next leader. The two most important questions surrounding the Labor leadership race are: one, how fast will Bill Shorten (pictured above) consolidate his support to become leader and, two, why is everyone within Labor so ready to hand the leadership to Shorten so quickly.

Shorten, a Melbourne MP who comes from the moderate, ‘Blairite’ wing of the party, served as president of the Australian Workers’ Union in the 2000s until his election to the House in 2007. He rose quickly, becoming financial services secretary and employment secretary after Labor’s reelection in 2010. He’s probably most well-known for his role in shaping the June leadership spill, when he dramatically announced shortly before the vote that he was switching his support from Gillard to Rudd.

Under the new party leadership rules that Rudd introduced in July, however, the next leader will be more difficult to remove — 60% of the Labor caucus will be required to call a mid-term leadership spill. That means that Labor may come to regret hastily anointing Shorten as its opposition leader — potentially as soon as next week, though his allies within Labor’s right wing, including AWU figures and other Gillard supporters, remain wary of Shorten for the role he played in Gillard’s downfall three months ago.

But the new party rules also, for the first time, give Labor’s regular membership 50% of the role of choosing a leader if the race is contested. That could introduce a radical new element if Shorten has competition from outgoing House leader and deputy prime minister Anthony Albanese or Chris Bowen, who has served as treasurer since Rudd’s return and narrowly retained his McMahon seat in the western suburbs of Sydney.

Rudd-Gillard redux?

Another question is whether the poisonous fighting between the Rudd and Gillard factions will end with today’s election.

The principals themselves seem resigned to move on. Gillard took a dignified leave from Australia’s parliament, and from the minute the Labor caucus replaced her with Rudd, she immediately ceded the spotlight to Rudd and has been notably absent from political affairs — a contrast to Rudd’s constant plotting after Gillard replaced Rudd in June 2010.

Rudd won his Griffith seat in Queensland (by a 53% to 47% two-party preference vote), so he’ll be returning to parliament for now, despite the not-so-quiet wishes of some of his colleagues who hoped that a Labor caucus without Rudd would turn to the future with greater ease.

But Rudd may still decide to leave parliament. There’s not much precedent for defeated former prime ministers sticking around parliament — Bob Hawke left parliament eight weeks after Paul Keating stole the Labor leadership from him in 1991, Keating resigned from parliament six weeks after leading Labor to national defeat in 1996, and Howard famously lost his own seat in the November 2007 landslide that swept Rudd initially to power. But Kevin Rudd being Kevin Rudd, don’t rule anything out.

Though it’s good news for Labor that former treasurer Wayne Swan retained his own Lilley seat in Queensland, it leaves Gillard’s most prominent champion in parliament alongside Albanese, a Rudd supporter. So even if Rudd and Gillard have called a truce, their supporters might find it hard to suture old wounds that divided Labor for much of its past six years in government.

2 thoughts on “At the dawn of the Abbott era of Australian politics, what comes next?”