On Thursday, Abdullah Gül, Turkey’s last indirectly elected president, will leave office after seven years.![]()

Officially, he’ll have no role in either Turkey’s government or in the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) that his successor, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, leads and that Gül himself co-founded with Erdoğan in 2001.

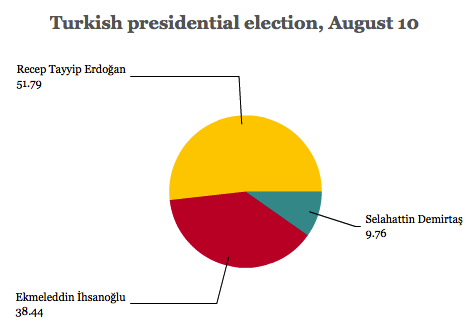

Erdoğan’s victory in Turkey’s first direct presidential election on August 11 cleared the way for his plans to transform Turkey’s government into a presidential system, the culmination of years of gradual centralization since Erdoğan first became Turkey’s prime minister in 2003.

Though Erdoğan will officially step down from any formal party and political role, he has made clear that he expects, unofficially, to direct both party and policy from his new perch at Çankaya Köşkü, the Turkish presidential palace, as the powerful leader of what he calls the ‘new Turkey.’ He’ll do so at first as a de facto leader. Late last week, the AKP chose Ahmet Davutoğlu, Turkey’s foreign minister since 2009, as its new AKP leader and, accordingly, Turkey’s new prime minister. In that role, Davutoğlu is widely expected to follow Erdoğan’s lead in governing Turkey.

* * * * *

RELATED: Erdogan wins first-round presidential victory

* * * * *

That leaves Gül, perhaps the only figure in the AKP more popular than Erdoğan, as one of the few people in Turkey who have enough political strength to stand up to his successor.

A year ago, the conventional wisdom was that Gül would trade places with Erdoğan and become prime minister, an office that Gül held briefly during the first four months of the AKP’s government. When the Islamists first won the 2002 elections, Erdoğan was still subject to a ban on his involvement in politics that the new government soon lifted. When Erdoğan subsequently became eligible for the premiership, Gül became Turkey’s deputy prime minister and foreign minister, launching Turkey’s accession talks with the European Union in 2005 and asserting a greater Turkish presence in the Middle East.

Despite some controversy over the rise of an Islamist to the Turkish presidency, Gül easily won the vote in Turkey’s National Assembly in 2007. As head of state, Gül generally observed presidential impartiality, though he courted controversy when he became the first Turkish president to visit Armenia and condemned Israel after it attacked an aid flotilla destined for Gaza in 2010.

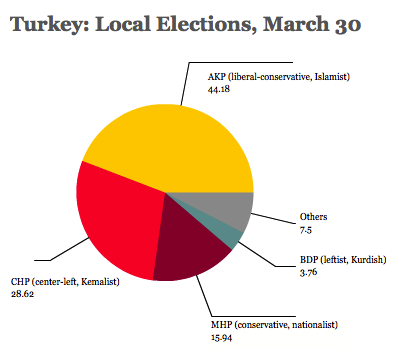

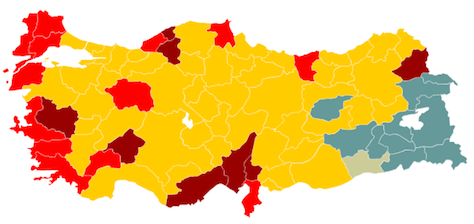

But Gül also chided Erdoğan’s response to 2012 protests, which began over plans to build a new mosque in place of Gezi Park in downtown Istanbul and grew to encompass the growing authoritarian manner of Erdoğan’s government. In particular, Gül directly criticized police forces for the brutality deployed against largely peaceful protesters. Gül further argued that democracy requires liberal freedoms and the rule of law, comments that further distanced Gül from Erdoğan. Gül also strongly resisted Erdoğan’s short-lived attempt to restrict Turkish access to Twitter in the prelude to March’s local elections.

Despite Erdoğan’s presidential victory, Turkey remains polarized over his leadership. Critics argue that Turkey is moving away from European-style democracy toward a more centralized style more reminiscent of Vladimir Putin’s rule in Russia. Though many moderates and secular Turks welcomed Erdoğan’s rise over a decade ago, when he effectively thwarted the corrupt secular leadership that ruled in tandem with a coup-prone military that routinely harassed political Islamists. But they increasingly worry that Erdoğan is so completely consolidating power that he’s becoming an arguably larger threat to Turkish democracy.

Gül has indicated his disapproval of Erdoğan’s plans and, in his farewell address as president, Gül pointedly defended his impartiality, decried political polarization and otherwise emphasized and his commitment to the rule of law, press and personal freedoms, the impartiality and independence of the judiciary and a secular state balanced by the freedom of religion.