It’s been a busy week, but it’s worth taking a moment to explore the results from Ukraine’s parliamentary election on October 28 in greater detail.

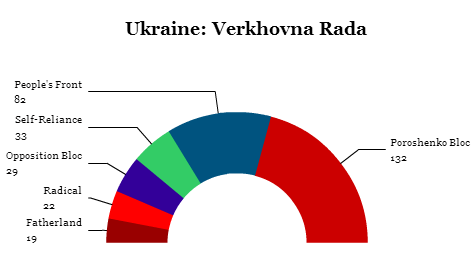

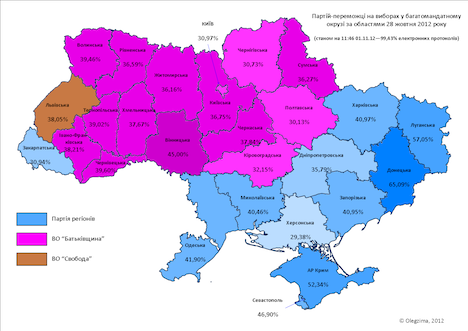

We have a final set of preliminary numbers now, which lines up with what exit polls had forecasted after polls closed Sunday night — the governing pro-Russian party of president Viktor Yanukovych, the Party of Regions (Партія регіонів), won just 30.08% of the vote, but it will take 42% of the seats in the 450-member Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s unicameral parliament. Indeed, Yanukovych and his allies quickly declared victory on Sunday night.

It was able to do so because of a change in the electoral law — in the previous election in 2007, all of the parliamentary seats were determined by proportional representation, but in 2012, half of the seats were elected through single-member districts, allowing Yanukovych’s united party to take advantage of a split opposition.

In this case, the opposition party of former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko, the center-right ‘All Ukrainian Union — Fatherland’ party (Всеукраїнське об’єднання “Батьківщина, Batkivshchyna) wound up competing, to some degree, with the new reformist Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform (Український демократичний альянс за реформи), formed by heavyweight boxing champion Vitaliy Klychko.

On the proportional representation vote, Yanukovych’s Party of Regions won 73 seats, versus 61 for Batkivshchyna/Fatherland and 34 for UDAR.

In the constituencies, however, Yanukovych’s party won 114 to just 42 for Batkivshchyna/Fatherland and a mere six for UDAR.

The result will be a parliamentary majority that gives Yanukovych and his prime minister Mykola Azarov slightly greater control over government.

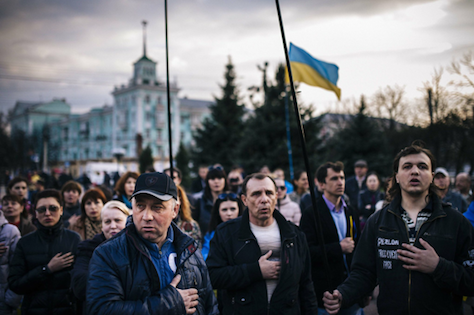

The somewhat fragmented results also show, however, an electorate that is none too pleased with Yanukovych’s increasingly authoritarian rule, his grip over Ukraine’s economy, the graft benefitting his friends and family, and the ongoing economic malaise, unemployment and stalled economic reform. Despite his apparent gains last Sunday, it’s not clear that Ukrainians — especially members of Ukraine’s increasingly fragile business elite — will remain pliant in the face of policies that pull the country further from the goal of eventual integration into the European Union.

Indeed, the victory comes in an election that was far from free and fair — the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe has a detailed report on the unfair advantages that Yanukovych brought to the election.

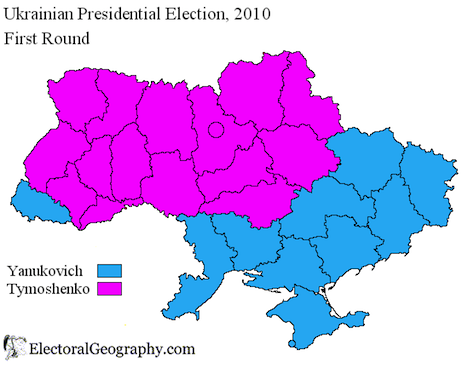

Tymoshenko, who served as prime minister in 2005 and then again from 2007 to 2010 under former reformist president (and ‘Orange Revolution’ leader) Viktor Yushchenko, narrowly lost the 2010 presidential election to Yanukovych. Since then, she has been imprisoned on politically-motivated charges stemming from her negotiation of an energy deal with Russia following a 2009 crisis when Russia stopped the flow of natural gas to Ukraine and to the rest of Europe. It’s puzzling, however, that the relatively more Russian-friendly Yanukovych would pursue those charges against the relatively more Europe-oriented Tymoshenko, and he certainly hasn’t bothered Moscow with a request to renegotiate the agreement. Indeed, Moscow will be happy to see gains for the pro-Russian party, following a month of elections in former Soviet republics generally seen as wins for Russia’s attempt to restore its influence in what it calls the ‘near-abroad.’

Nonetheless, Tymoshenko’s support held up despite her imprisonment, with her party winning 25.47% of the vote. That’s in no small part due to the capable leadership of Arseniy Yatsenyuk, who served as minister of the economy from 2005 to 2006, foreign minister in 2007 and chairman of the Verkhovna Rada from 2007 to 2008. Although the party will have lost 53 seats since the last parliamentary election in 2007, they will retain the strongest opposition group in Ukraine’s parliament — by far. It’s a tactical and political victory for Yatsenyuk, of course, who could well be the opposition presidential candidate in 2014, but it’s also a moral victory for Tymoshenko, whose imprisonment now remains the primary symbol of Ukraine’s legal, democratic and economic backslide under Yanukovych.

Although it was UDAR’s first elections in Ukraine, Klychko will have been disappointed to have won just 13.92% and 40 seats. Surely, Klychko hoped that his campaign would install him as the major opposition figure in Ukraine and perhaps given him an opportunity for a knockout punch against Yanukovych as well. That’s clearly not going to be the case, although Klychko has established himself as a key reformer in Ukraine, and I expect his bloc of reform-minded MPs will certainly work with Batkivshchyna/Fatherland to make the case for liberalization, other economic reforms, rule of law, and keeping Ukraine’s wider orientation toward eventual European Union membership.

But Klychko’s support was not much more than the other major parties in Ukraine — for example, the Soviet retro Communist Party (Комуністична партія України), which has allied with Yanukovych in the past, won 13.20% and 32 seats.

More troubling, the far-right nationalist All-Ukrainian Union “Svoboda” (Всеукраїнське об’єднання «Свобода») won 10.42% and 37 seats. Although Svoboda, like UDAR and Batkivshchyna/Fatherland, opposes making Russian a national language in Ukraine, the similarities stop there — think of Svoboda as closer to Greece’s Golden Dawn than to, say, a moderately nationalist Christian democratic party in Western Europe. Continue reading More final thoughts on Ukraine’s election and Tymoshenko’s future →

![]()