Despite what you may believe from the example of Egypt and from the various ‘color’ revolutions of the past decade, power isn’t transferred by popular revolt, at least not in mature democracies.![]()

That’s important to bear in mind as much of the US and international media keeps its attention focused on Kiev, where protesters continue to demand the resignation of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, who is largely seen as favoring closer ties to Russia than to the European Union and the West. Despite last weekend’s protests of up to 250,000 Ukrainians, which featured violent clashes with the police (the Ukrainian government has since apologized), Yanukovych has so far survived the blowback from his decision last month to reject an association agreement that would have brought Ukraine into closer alliance with the European Union. While the most conspiratorial commentators believe that Yanukovych rejected the agreement at the insistence of Russian president Vladimir Putin, a more plausible explanation is that Yanukovych hopes to avoid the kind of short-term disruption to Ukrainian industry that could result from opening Ukraine’s markets to European-wide competition just months before he hopes to win reelection in February 2015. Theres also plenty of blame for the European Union itself, which didn’t go out of its way to make the path for Ukraine incredibly easy, in light of Ukraine’s longstanding relationship with Russia.

But too much of the international media’s coverage attempts to frame the Ukrainian protests as some kind of ‘Orange Revolution’ redux, with Western media almost gleefully urging Yanukovych’s overthrow by mob acclamation.

It’s true that Yanukovych is relatively pro-Russian and many of his opponents are relatively pro-Western, and it’s very true that Yanukovych’s record is littered with authoritarianism and corruption. But that interpretation both overstates the differences among the Ukrainian political elite (when hasn’t Ukraine been relatively corrupt?) and it understates the massive economic, demographic and social problems that Ukraine has faced since the end of the Cold War. The much-hyped Orange Revolution didn’t settle the question of Ukraine’s relative identity vis-à-vis Russia and the West, and the current round of protests won’t likely settle the question either.

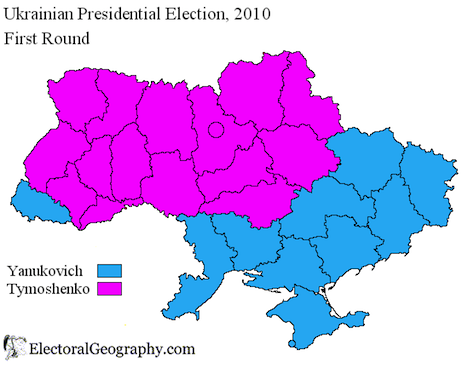

Here’s a look at the map of the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election results, which pitted Yanukovych against the relatively pro-Western Yulia Tymoshenko, a former prime minister who is now jailed on what many agree to be politically motivated charges:

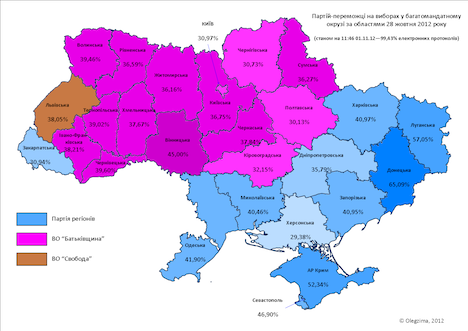

Here’s a look at last October’s parliamentary election results — blue represents Yanukovych’s governing party, the Party of Regions (Партія регіонів), and pink represents Tymoshenko’s party, the center-right ‘All Ukrainian Union — Fatherland’ party (Всеукраїнське об’єднання “Батьківщина), which emerged as the largest opposition party:

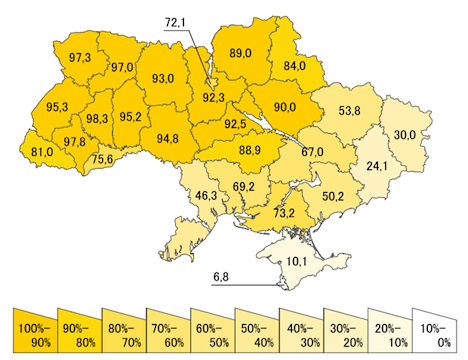

Now here’s a map of Ukraine’s regions that shows the percentage of the regional population that speaks Ukrainian (rather than Russian):

Notice any similarities?

You should — the lesson here is that Ukraine is split between a western Ukrainian-speaking population and an eastern Russian-speaking population that’s divided not only by language, but by cultural, political and economic differences.

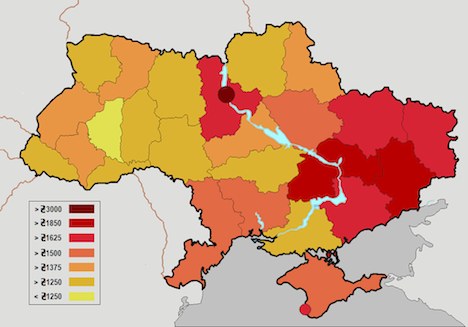

Here’s a look at average salary by region, for example, which shows that the Russian-speaking east, where many of Ukraine’s major cities are located, is economically stronger than the Ukrainian-speaking west, except the region surrounding Ukraine’s capital Kiev (and, to a lesser degree, the region surrounding Odessa on the Black Sea coast, where tourism boosts the local economy):

It’s difficult to overstate the differences between the ‘two Ukraines.’ Continue reading Why more protests won’t solve Ukraine’s political crisis (and why the Orange Revolution didn’t, either)