Tokyo certainly seems to have a fondness for electing colorful characters as its governors — and its newly elected governor appears like he will be no exception.

Tokyo certainly seems to have a fondness for electing colorful characters as its governors — and its newly elected governor appears like he will be no exception.

Yōichi Masuzoe (舛添 要), who easily won the Tokyo gubernatorial election on Sunday, first became well-known in the 1990s as a television commentator. In 1998, he wrote a book, When I Put a Diaper on My Mother, which detailed the process of caring for his elderly mother and gave Masuzoe a platform to discuss health and aging in Japan. That’s particularly relevant for Japan, which has the world’s second-highest median age (44.6, just 0.3 years higher than Italy), and where the population peaked at just over 128 million in 2010 in what demographers believe will be a massive depopulation over the coming decades.

Masuzoe (pictured above) first ran for the Japanese governorship in 1999, though he placed third with just 15.3% of the vote. Elected to the House of Councillors, the upper house of the Diet (国会), Japan’s parliament, in 2001, Masuzoe rose through the LDP ranks. He chaired a constitutional panel in 2006 that advocated amending Japan’s Article 9, thereby allowing the Japanese Self-Defese Forces to become a full army. Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三), who was then in his first stint as Japan’s prime minister, appointed Masuzoe as Japan’s minister for health, labor and welfare, a position he held between 2007 and 2009, when the LDP suffered its most severe postwar electoral defeat.

He left the LDP in 2010 to form the New Renaissance Party (新党改革) at a time when his national profile seemed to be rising. But by the time a national election came along in December 2012, the LDP was set to win a landslide victory under Abe and his economic program, popularly dubbed ‘Abenomics.’ Eclipsed by the Japan Restoration Party (日本維新の会), a merger of the two new parties of Tokyo’s governor at the time, Shintaro Ishihara (石原 慎太郎), and Osaka’s young mayor, Tōru Hashimoto (橋下 徹), the New Renaissance Party failed to win a single seat.

Today, the Japan Restoration Party is setting its sights somewhat lower after a disappointing result in the July 2013 elections to the House of Councillors and a series of bad publicity for Hashimoto, who defended the use of ‘comfort women‘ by Japanese soldiers in World War II in May 2013, has called snap elections in Osaka, where he’ll stand for reelection after proposing the merger of Osaka’s city and prefectural governments.

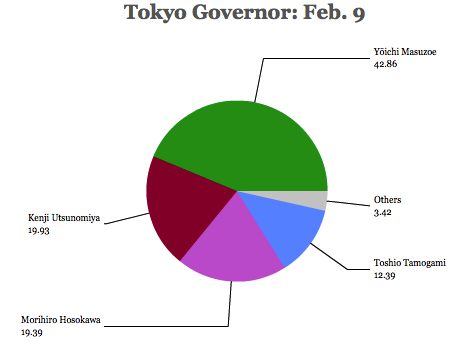

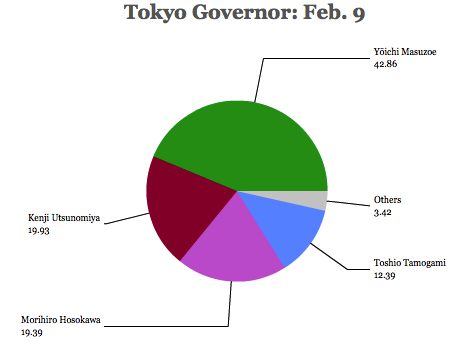

But Masuzoe is today riding high — running as an independent with the support of the LDP and its conservative Buddhist ally, New Kōmeitō (公明党, Shin Kōmeitō), Masuzoe won the election in a near-landslide, garnering more than double the support of his nearest challenger, Kenji Utsunomiya (宇都宮 健児), a Japanese attorney and anti-nuclear activist, and the runner-up in Tokyo’s December 2012 gubernatorial election.

In third place was the man who once threatened to knock Masuzoe from his frontrunner perch — Morihiro Hosokawa (細川 護煕), who served as prime minister between August 1993 and April 1994, leading the first non-LDP government since 1955. Though he resigned over accusations of bribery, and thereupon left politics, the DPJ recruited him for the 2014 Tokyo race.

Though Hosokawa had the formal support of the DPJ and Masuzoe the formal support of the LDP, several top Democratic Party figures backed Masuzoe. Junichiro Koizumi (小泉 純一郎), the LDP architect of economic reform in the 2000s, backed Hosokawa, in large part due to his anti-nuclear stance.

In contrast to Utsunomiya and Hosokawa, who pledged to limit spending on the 2020 Olympics and opposed a return to nuclear energy, Masuzoe supported return to nuclear energy and now stands a good chance of ushering Tokyo through to the 2020 Olympics with plenty of LDP patronage, though Masuzoe will face reelection in 2018. Earlier Monday, Abe’s government appeared to push with renewed vigor to restore Japan’s nuclear power capability just three years after the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, and at times, the Tokyo gubernatorial race felt like a showdown between Abe and Koizumi, arguably the two most successful political figures in Japanese history of the past two decades.

The truth is that Tokyo voters weren’t thinking about the contest as a referendum on nuclear power, but competent city governance. Abe, still basking in the success of his economic program (though that success may be somewhat less impressive than it was half a year ago), was always going to cast a large penumbra in the race.

Moreover, Utsunomiya and Hosokawa split the mostly anti-Masuzoe vote — had they united, they would have stood a strong chance at overtaking him, thereby denting the political invincibility that Abe and the LDP have enjoyed since December 2012. The fourth-place candidate, Toshio Tamogami, a former general in the Self-Defense Forces, waged a largely nationalist, militaristic campaign, enough to win 12.4% of the vote that might have otherwise gone to Masuzoe.

Masuzoe expressed other odd views during the campaign — he indicated, rather bizarrely, that he didn’t believe women were capable of leading the country, inspiring an equally ‘sex boycott‘ among Tokyo women.

Back in Tokyo, Masuzoe is in good company historically though, given that the Tokyo governorship has attracted some of Japan’s most colorful politicians on the left and the right.

Continue reading Who is Yoichi Masuzoe? →

![]()