The result of today’s state elections in Bavaria has both good news and bad news in terms of Angela Merkel’s hopes to win a third term as chancellor in exactly one week.![]()

![]()

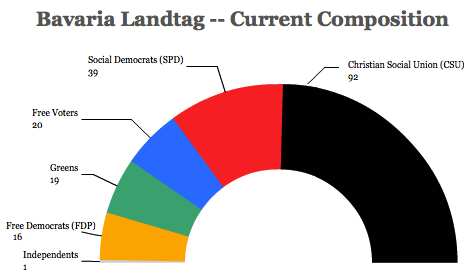

With results still coming in, the center-right Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, the Christian Social Union) will improve vastly upon its historically poor result in the prior September 2008 election, giving Bavaria’s minister president Horst Seehofer (pictured above) an absolute majority in the 187-member Landtag, Bavaria’s unicameral state parliament.

The current projection gives the CSU 101 seats, with just 43 seats for the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) and 18 seats each for Die Grünen (the Greens) and the center-right group of independents, the Freie Wähler (FW, Free Voters).

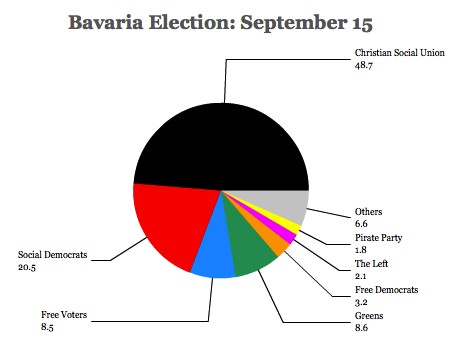

Here’s the latest snapshot of the result:

That’s great news for the CSU, which has controlled Bavaria’s state government consecutively since 1947. The Bavarian-based CSU is the sister party of Merkel’s Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party), which competes everywhere else in Germany, and the two parties work together as a union for federal political purposes. So the fact that the CSU increased its support by over 5% in what was already a center-right heartland is a sign that Merkel will be able to drive up the number of seats that the CDU/CSU will win in next week’s federal elections.

It’s an amazing turnaround for the CSU, which won less than 44% five years ago and was polling just 40% as recently as 2010. It’s a huge win for Seehofer personally as well, given that his personality dominated the CSU’s presidential-style campaign, the same tactic that Merkel and the CDU have deployed for next week’s federal elections. It puts Seehofer alongside recent CSU leaders who have dominated Bavaria’s recent past, such as Franz Josef Strauß in the 1970s and 1980s and Edmund Stoiber in the 1990s and 2000s. Given the relative strength of the Bavarian economy vis-à-vis Germany and, especially vis-à-vis Europe, the CSU’s win is not surprising — Bavaria’s reputation long ago solidified its image as the land of laptops und Lederhose.

But it’s horrible news for the liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), which won just 3.2% today, falling far short of the 5% threshold required to win seats in the Landtag.

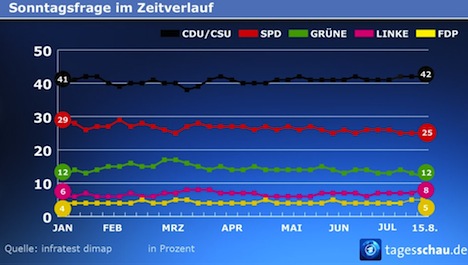

Seehofer and the CSU depended on a governing coalition with the Free Democrats for the fast five years, and Merkel and the CDU/CSU govern in coalition with the Free Democrats at the federal level as well. Since riding a wave of popularity in the late 2000s (the Free Democrats won nearly 15% of the vote in the 2009 federal elections), its public support collapsed shortly thereafter. After a series of poor performances in state elections, foreign minister Guido Westerwelle stepped down as the party’s leader. But its new leader Philipp Rösler, Germany’s first Vietnamese-born party leader, has hardly done much better. Under his leadership, though, the Free Democrats actually gained support in two key state-level votes — in the May 2012 North Rhine-Westphalia election and the January 2013 Lower Saxony state elections.

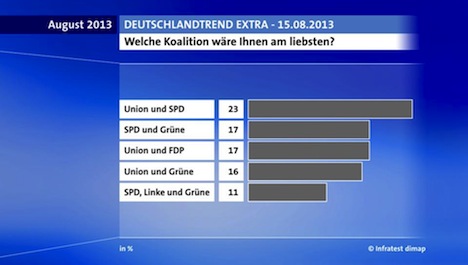

The FDP’s loss in Bavaria comes at a devastating time, however. Seehofer and the CSU in Bavaria will no longer need a coalition partner, but that’s not likely to be the case for Merkel next week, so Merkel needs the Free Democrats to perform much better nationwide in seven days. While Merkel’s CDU/CSU widely leads in the polls in advance of next week’s federal election, Merkel is unlikely to win the kind of outright majority that Seehofer won today (because the rest of Germany tilts further to the center and to the left than the Catholic, socially conservative Bavaria). Just as for Bavaria’s state elections, there’s a 5% threshold for winning seats on the basis of proportional representation in the Bundestag, the lower house of Germany’s national parliament, and polls show the Free Democrats treading at about 5% support nationally.

So if the Free Democrats win less than 5% next week, Merkel will be forced to look to other alternatives: an unstable minority government, return to a ‘grand coalition’ with the rival Social Democrats or a more creative solution, such as a ‘black-green’ coalition with the Greens. Even if the Free Democrats win more than 5%, their ranks are likely to be so decimated that Merkel may be forced into an alternative anyway. Continue reading FDP shut out of Bavarian parliament, CSU wins absolute majority