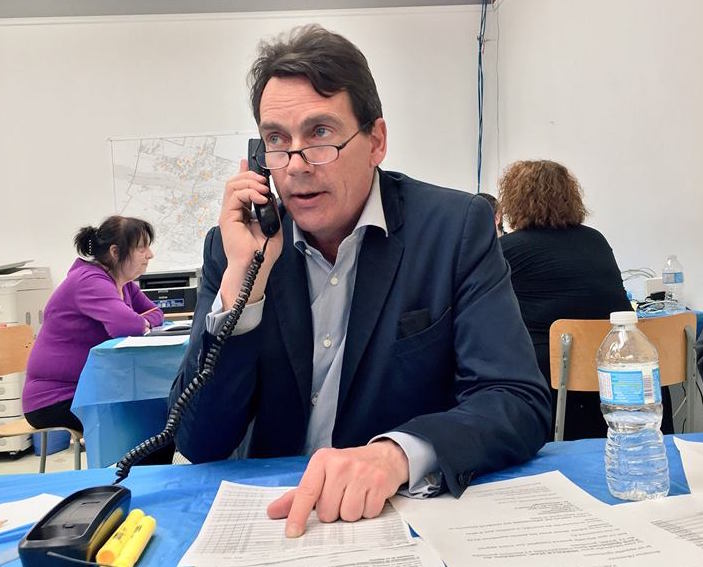

Less than a year into his tenure as the leader of the sovereigntist Parti québécois, Pierre Karl Péladeau abruptly stepped down on Monday, sending political shocks waves throughout Canada’s majority French-speaking province.![]()

![]()

Four months after a sudden split with the wife he married in August, and now facing a custody battle over his children, Péladeau abruptly announced his resignation from the PQ leadership and from the provincial assembly, tearfully explaining that he had chosen to put his family before his ‘political project.’

Péladeau’s departure leaves the province without a full-time opposition leader, and the PQ’s troubles could cause voters to turn to an increasingly crowded field of nationalist alternatives. It’s just the latest setback for a party that’s suffered two tough decades after coming just 55,000 votes shy of winning Québec’s independence in 1995.

Jean Charest, premier for nine years as the leader of the centrist Parti libéral du Québec (PLQ, Liberal Party of Québec), sidelined the separatists for nearly a decade. For a while, the PQ fell to third place after the 2007 elections. The party’s leader at the time, André Boisclair, the first openly gay party leader in Canadian history, spent much of his leadership alienating the party’s rural, unionized base and fending off charges of drug use and financial malfeasance.

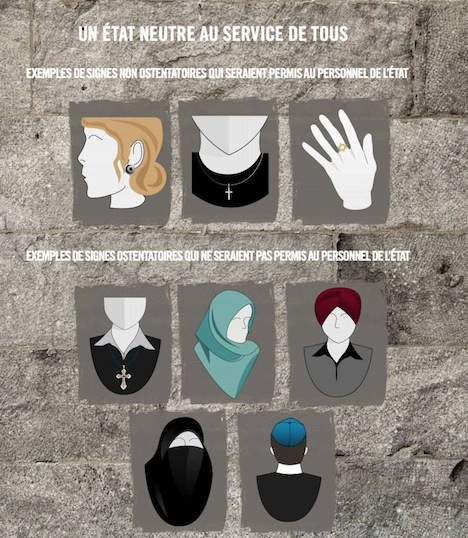

When voters finally gave the PQ a shot at governing in 2012, under Pauline Marois, the party immediately launched a needless effort to introduce the ill-named Charte de la laïcité (Québec Charter of Values), which served only to alienate recent immigrants to the province, especially Muslims, by purporting to ban religious headgear.

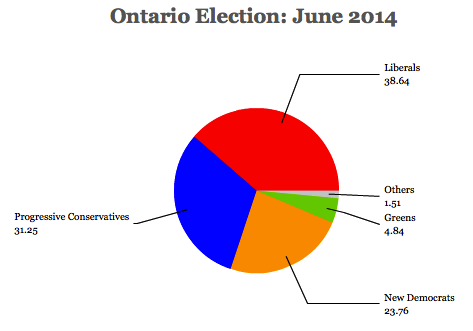

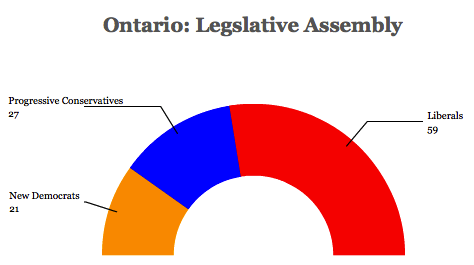

After Marois called early elections in a disastrous effort to win a majority government, voters instead turned back to the PLQ under its new leader, Philippe Couillard, a former provincial health minister. Marois quickly lost control over the debate when a new star recruit — Péladeau — stood on a campaign platform with Marois and, fist raised, started calling forQuébec’s independence. That forced Marois to respond to hypotheticals about a third referendum, whether an independent Québec would use the Canadian dollar and how borders would work between Canada and an independent Québec. The PQ dropped to its lowest total yet — barely over 25% of the vote.

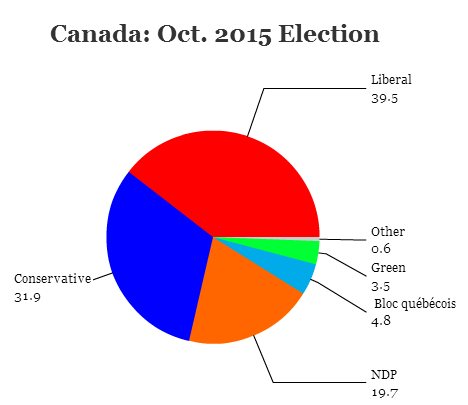

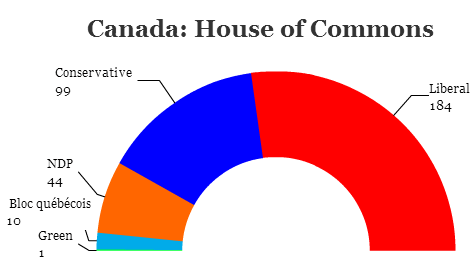

Meanwhile, its sister party, the Bloc québécois (BQ), won less than 20% of the vote in the 2015 Canadian federal election, and its leader, Gilles Duceppe, resigned (again) after failing to win his own riding. Its 10 seats in Canada’s House of Commons is somewhat better than the four seats it won in the 2011 election, but the days when the BQ dominated the province’s representation in Ottawa now seem long gone.

After a needlessly long internal campaign, Péladeau emerged last spring as the easy winner of the PQ’s leadership election, and he defiantly vowed to make Québec a country. Almost immediately, however, Péladeau’s stumbles seem to outweigh his charms. He indulgently refused to sell the shares to Quebecor the media empire that his father once ran and that Péladeau himself ran until his decision to enter provincial politics. His business-friendly demeanor met with skepticism from the party’s left-wing members and union activists. Many of them left the PQ for the more stridently leftist and pro-independence Québec solidaire.

Meanwhile, Péladeau was never able to steal votes from the ‘soft’ nationalist, center-right Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ), which dominates the vote in and around Québec City. Péladeau’s hardline calls to make Québec a country nearly guaranteed that the PQ would not be the beneficiary of the Couillard government’s growing unpopularity due, on doubt, to two years of spending cuts aimed to achieve a balanced budget. Though the most recent CROP poll from mid-April gave the Liberals just 33% support, the PQ drew just 26%, compared to 25% for the CAQ and 14% for Québec solidaire.

Having already announced the province’s 2016 budget in March, and basking in a Delta Airlines decision to buy 75 aircraft from local manufacturer Bombardier, it would not be the worst time for Couillard to call an early election.

In one sense, Péladeau’s resignation gives the party a fresh start as the province starts the countdown to new elections, to be held before October 2018. Under a long interim leadership, the PQ might continue to lose right-leaning supporters to the CAQ and left-leaning supporters to Québec solidaire. The next election will be François Legault’s third as the CAQ leader, and it will be Françoise David’s fourth as co-spokesperson for Québec solidaire, and both remain incredibly popular.

But there was a sense that Péladeau’s victory last May was the last shot for the péquistes to regroup, with increasingly bilingual young voters and rising numbers of immigrants, in particular, rejecting any abrupt separation with Canada. Demographics just aren’t in the PQ’s favor, and its next leader will have none of the name recognition or star power that Péladeau, for all his faults, brought to the PQ leadership.

Alexandre Cloutier, a 38-year-old former minister and currently, shadow education secretary, ran second in last year’s PQ leadership race, and could provide a Trudeau-like appeal to younger voters.

Jean-Martin Aussant, who left the PQ in 2012 to form Option nationale, dedicated to a more impatient brand of Québécois sovereignty, and who flamed out of provincial politics, could return as a 21st century version ofJacques Parizeau, the fiery champion of the independence movement.

Bernard Drainville, who masterminded the Marois government’s push for the Charter of Values, is another possibility, as is Jean-François Lisée, who served as minister of international relations and trade under Marois.

No doubt, old-timers will hope that the 68-year-old Gilles Duceppe, the BQ leader from 1997 to 2011 (and again, briefly, in the leadup to the 2015 election) will attempt one more comeback for the separatist cause.

Even before Péladeau’s resignation, the PQ was already facing an existential problem as a party dedicated to independence in a province where the most separatist generation is literally dying out. In a country where even former Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper can call Québec a ‘nation’ without any major blowback, and where its current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, comes from Montréal’s most storied political dynasty, the PQ’s raison d’être seems even more like yesterday’s cause. Neither Péladeau nor his successor is likely to pick a fight with Trudeau, massively popular in Québec just as much as the rest of Canada, over sovereignty.

No matter who the PQ chooses as its next leader, he or she will face difficult odds to convince Québec’s youth, its growing immigrant class and anglophones to support it as the chief alternative to Couillard’s Liberals in a political marketplace that’s more crowded with ‘nationalist’ parties than ever. In trying to be all things to all nationalists, the PQ risks its very extinction.