For nearly two decades, the most dominant force in Québec politics was the Bloc québécois, a sidecar vehicle to the province-level Parti québéecois that has fought, more or less, for the French-speaking province’s independence for the better part of a half-century.![]()

![]()

From 1993 until 2011, the BQ controlled nearly two-thirds of all of Québec’s ridings to the House of Commons. In the mid-1990s, with western and eastern conservatives split, and the Jean Chretién-era Liberal Party dominating national politics, the BQ held the second-highest number of seats in the House of Commons, making the sovereigntist caucus, technically speaking, the official opposition.

That all changed in the 2011 election, when the New Democratic Party (NDP) breakthrough made it the second-largest party in the House of Commons. It did so nationally by stealing votes from the Liberals, but it did so in Québec in particular by poaching votes from the Bloc, whose caucus shrank from 47 members to just four.

Moreover, as the BQ heads into October’s general election, its caucus has dwindled to just two seats, due to defections, and there’s a good chance that the party will be wiped out completely in 2015.

If it is, and the BQ époque firmly ends next month, it could send a chilling lesson to separatist movements throughout the developed world. Most especially, it’s a warning for the Scottish National Party (SNP), which is riding so high today — the SNP controls a majority government in Scotland’s regional assembly and it won 56 out of the region’s 59 seats to the House of Commons in the United Kingdom’s May 2015 general election. But the lesson for the SNP (and other autonomist and separatist parties) may well be that there’s a limit to protest votes, especially if electorates believe that nationalist movements like the SNP or the Bloc can neither extract more concessions from national governments or take part in meaningful power-sharing at the national level.

The Bloc‘s collapse in the early 2010s might easily foretell the SNP’s collapse in the 2020s for exactly the same reasons.

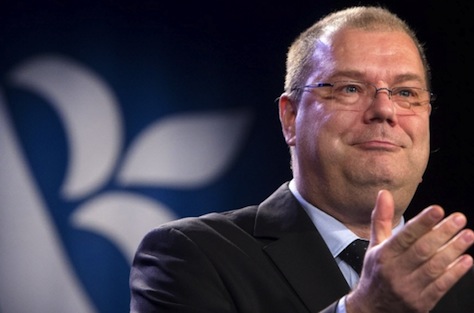

The return three months ago of the Bloc‘s long-time former leader, Gilles Duceppe (pictured above), was supposed to restore the party’s fortunes. Instead, the 68-year-old Duceppe risks ending his political career with two humiliating defeats as the old and weary face of an independence movement that has little resonance with neither young and increasingly bilingual Quebeckers nor the deluge of immigrants to the province for whom neither French nor English is a first language. Some polls even show that Duceppe will lose a challenge to regain his own seat in the Montréal-based riding of Laurier-Sainte-Marie, where voters preferred the NDP’s Hélène Laverdière in 2011.

Outliving its usefulness?

The BQ’s collapse at the national level holds important consequences for Canada’s federal politics. Without the Bloc‘s lock on one-sixth of the House of Commons, it becomes much easier to win a majority government. Even in the event of a hung parliament, though, assembling a majority coalition will still be easier for the three major parties, because none of the Conservatives, the Liberals or the NDP would risk forming a coalition with Québec MPs who want to leave Canada. More importantly, with the Bloc no longer holding so many ridings in Québec, Canada’s second-most populous province, it opened the way for the NDP’s rise in 2011. In retrospect, the NDP’s social democratic roots were always a natural fit for Québec’s chiefly left-of-center electorate. The NDP’s continued strength in Québec in the present campaign means that it is a serious contender to form the next government.

The most recent CBC poll tracker average, from September 14, shows the NDP leading with 42.8%, far ahead of the Liberals, with 25.7%, the Conservatives, with 14.9%, and the anemic Bloc, with just 13.2%. In one sense, the Bloc‘s demise is a kind of success story. Canada’s Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper long ago agreed that Québec is a ‘nation’ within Canada, and he has quietly boosted the federal funds that the province receives, all while trying to lower the volume when tensions arise between Québec and the national government. No matter who becomes prime minister in October, there’s no real appetite for a return to the bruising constitutional battles of the 1980s and 1990s.

Harper’s government shrewdly tamped down western Canada’s anger over what was, in effect, the subsidizing of Québec and its more statist and welfare-heavy provincial government. That could change, especially if the global drop in oil prices permanently depresses regional economies in Alberta and British Columbia. For now, however, a more united Canada is among Harper’s most important (and least heralded) legacies.

An existential crisis for the Québec independence movement

After 2011, the party’s fortunes were already bleak. Its loss of so many seats meant a corresponding loss in federal campaign funding. After Duceppe originally stepped down, his successor, Daniel Paillé, stepped down due to health reasons after just two years as BQ leader.

But the Bloc deteriorated even further under Mario Beaulieu (pictured above), who succeeded Paillé in June 2014. The head of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, a hardline pro-independence group that works fiercely to protect and defend the use of the French language. Beaulieu had a history of incendiary statements, and two of the Bloc‘s four MPs immediately quit the party as a result of Beaulieu’s ascension, including André Bellavance, who had challenged Beaulieu for the leadership (and narrowly lost). Beaulieu won the leadership by promising to double down on the cause for independence, leading to severe backlash from both inside and outside the province:

Mr. Beaulieu has no charisma, he is not a good public speaker and he has never said or written anything memorable, apart from his anti-English diatribes and his knee-jerk, independentist rhetoric. His latest exploit is a video in which he acts as a tour guide showing how Montreal has been totally submerged by English – a ridiculous, paranoid delusion.

Beaulieu stepped aside a year later, however, ceding the leadership back to Duceppe and admitting that his hardline approach was not attracting new voters.

Though Duceppe led the Bloc to its 2011 defeat, it followed a stunning five-election run for Duceppe that began in 1997 and saw the party dominate each subsequent federal election. Duceppe has argued that, this time around, the NDP will be weaker without its beloved 2011 leader, the late Jack Layton. That flies in the face of polls that have consistently shown that Quebeckers still prefer the NDP without ‘le bon Jack‘. Thomas Mulcair, who succeeded Layton as NDP leader and as Canada’s opposition leader, grew up in the province and served as Québec’s environmental minister under Liberal premier Jean Charest. If anything, Mulcair’s claim on the province is even stronger than Layton’s ever was.

But there’s an even more fundamental reason to doubt Duceppe will repeat the magic that he wielded for so long: the growing disenchantment of the province’s voters with the separatist movement. Since the last federal election, Québec has gone through two provincial elections, and the trend for Duceppe and the Bloc should be highly disconcerting. Québec’s voters in 2011 were on the cusp of electing a separatist government; in 2015, they have firmly rejected that government.

In the lead-up to the 2011 election, provincial voters were just 16 months away from ending Charest’s nearly decade-long rule and returning the PQ to power at the provincial level. But in April 2014, voters ended Pauline Marois’s short-lived, gaffe-plagued pequiste minority government. In so doing, they gave Québec’s government back to the steadier hand of majority government under the control of the Parti libéral du Québec (PLQ, Liberal Party of Québec) and the well-regarded Philippe Couillard, a former health minister who now serves as premier.

The PQ, which recently elected media tycoon Pierre Karl Péladeau as its own leader, could yet emerge in the decade ahead as a more business-friendly alternative. But there’s no doubt that both the PQ and the BQ, as the provincial and federal fronts of the Québécois independence movement, are facing an existential crossroads. The BQ’s impending loss of the last remnants of its once muscular federal presence will only cast further doubt on the sovereigntist cause.

The separatist movement followed the province’s so-called ‘Quiet Revolutions’ of the 1960s that shook off its conservative parochialism. Subsequent provincial governments introduced legislation designed to boost the use of the French language, and the province held two referenda, one in 1980 and another in 1995, on separating from Canada, the latter lost by the narrowest of margins.