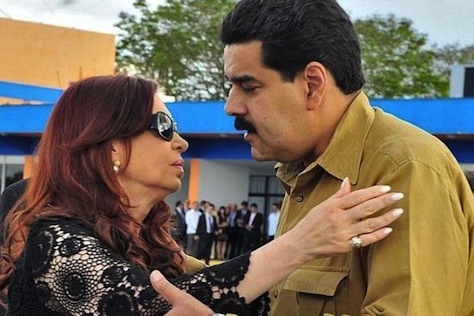

Earlier this month, Venezuela held municipal elections — the last set of elections that will take place until the end of 2015.

The results came after an extraordinary month in Venezuela, when president Nicolás Maduro obtained an Enabling Law, a decree for extraordinary powers from the Asamblea Nacional (National Assembly), a radical step that gives Maduro fast-track powers to regulate the Venezuelan economy for a year. At the time, Diosdado Cabello, the president of the National Assembly, said that Maduro asked the National Assembly to ‘pass all the laws necessary to wring the necks of the speculators and the money launderers.’ In an even more radical move earlier that week, Venezuelan forces commandeered top electronics retail chain Daka, forcing price cuts that launched a frenzy of consumer spending at low prices. Critics called the spectacle the ‘CaDakazo,’ a play on the 1989 Caracazo riots, protests and looting in response to the government’s decision to implement an IMF reform package of significant fiscal adjustments.

Short of a magical rise in the price of oil, Venezuela’s inflation (already around 54% this year), the shortage of basic goods and services (fueled by rise in dependence on imports and a shortage of dollars), and increasingly troubled finances mean that Venezuela’s economy will only worsen over the next two years. Despite all that Venezuela’s been though in the past 14 years since Chávez first took power, the current economic crisis could get much, much worse. Maduro’s first year in office has the feel to it of the first 30 minutes of a really chilling horror film — you know you have another 90 minutes of terror ahead of you, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

In light of the massive government-forced handout of retail electronics in November, it’s not surprising that the governing Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV, United Socialist Party of Venezuela) won a greater share of the vote than the umbrella opposition group, the Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD, the Democratic Unity Roundtable). The actual numbers vary, depending on which third parties you classify as PSUV/Maduro supporters, which you classify as opposition allied with Capriles and the MUD and which are really, truly independent.

But generally speaking, the chavistas won around 48.8% to just 40.8% for the MUD. Though the opposition dominated Venezuela’s urban centers and it easily retained the mayor’s office in Caracas, it won Barinas (the state capital of Chávez’s home state), Valencia and Barquisimeto. But it only narrowly held on in Maracaibo, the second-most populous city, and the national vote tally is much worse than in April, when Capriles very narrowly lost the presidential election to Maduro. Though Capriles appears to command unity as the leader of the united opposition, there are cracks in the unity — popular opposition figure Leopoldo López has argued for a stronger street presence and a more muscular opposition to Maduro. López’s party Voluntad Popular (Popular Will) performed especially well in the local elections, and you should expect to see and hear much more from López in 2014 and beyond.

But where does Venezuela go from here? There are 24 months until the next major Venezuelan elections, the parliamentary vote to determine the composition of the National Assembly. In a country like Venezuela, where the economy is rapidly disintegrating, that’s quite a long time for the status quo to hold. Stunts like the ‘CaDakazo’ can only buy Maduro and the PSUV short-term delays — they don’t constitute long-term solutions for Venezuela’s growing economic crisis.

Imagine for a moment that you’re sitting in Miraflores, the Venezuelan presidential palace, and the future that you see is massive hyperinflation, continued shortages and economic decline. You don’t face the prospect of a recall for three more years, and you wouldn’t face reelection until 2019. So why worry about Capriles and the MUD? Wouldn’t you be most worried about internal PSUV threats? Like Cabello, a crafty operator with plenty of ideological flexibility, who has a separate power base from his perch as the president of the National Assembly. Perhaps you’d be worried about another young chavista, with the same kind of charisma as Chávez had, rising up to reclaim the ‘true’ mantle of chavismo. The Venezuelan military currently supports Maduro, but given sufficient time, might they reach a point where the economy (and the accompanying social unrest) becomes so bad that they intervene themselves?

When Maduro replaced longtime finance minister Jorge Giordani, an instinctive central planner, with the more pragmatic former central bank president Nelson Merentes, there was a brief window when fundamental economic reform seemed like a possibility. But with local elections looming, Maduro doubled down on state intervention in the economy — Giordani, who remained planning minister, continues to wield more influence over policymaking, and Rafael Ramírez, the longtime energy minister, replaced Merentes as Venezuela’s vice-president for economic matters in October.

Having essentially won those elections, Maduro has some breathing space to take the kind of steps that could give Venezuela’s economy a chance, though time is running short. Moody’s already downgraded Venezuelan debt to Caa1 last week — essentially, junk status.

The current problem of shortages are due to the fact that Venezuela is bringing in fewer dollars, which in turn must support rising demand for imports.

That’s partly due to the long-term economic tectonics of a petrostate — in Venezuela (as in Saudi Arabia or Qatar), it’s easier to get your hands on oil wealth than it is to try to generate new wealth. Over time, that means non-oil industries wither as the country becomes more dependent on oil revenues to finance other goods and services. But chavismo has made this worse — 14 years of ad hoc expropriations of Venezuelan businesses severely exacerbated the effect. The long-term solution is to find a way to diversify Venezuela’s economy away from oil, while maximizing the effectiveness of Venezuela’s oil wealth. When a country with as much oil as Venezuela is importing refined oil products from the United States, there’s clearly a problem with overdependence on imports.

What’s staggering is that Venezuela still reportedly has a trade surplus — so while it still might technically be able to afford its costly import habit, it’s getting harder and harder to feed that habit. After all, many Venezuelans have other uses for dollars than importing toilet paper for resale.

So what’s a former-bus-driver-turned-president to do? Continue reading After local elections, what next for Venezuela’s government? →

![]()