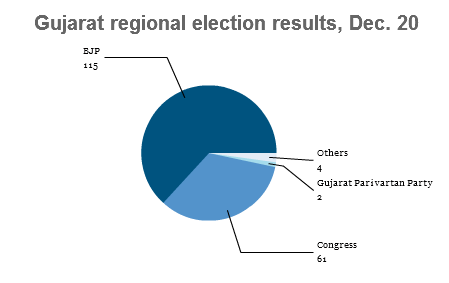

It’s nearly a year before Indians will go to the polls in the world’s most populous election, but Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi looks ever more like the man with the easiest path to become India’s next prime minister.![]()

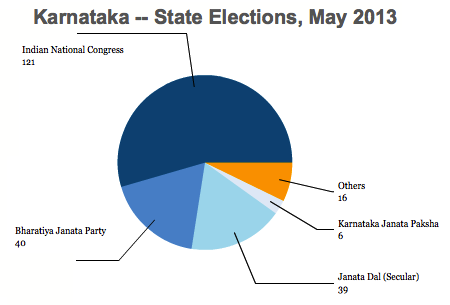

Eleven months is a long time in the politics of any country, so there’s no guarantee, and even if Modi winds up as prime minister, it will be after a long-fought slog. But the decision last week of the conservative Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, or भारतीय जनता पार्टी) to anoint Modi as the leader of its 2014 parliamentary campaign makes Modi the indisputable, if unofficial, leader of the BJP efforts to regain power after what will be a decade-long hiatus in opposition.

Modi faces plenty of obstacles, too, within his own party and the wider National Democratic Alliance coalition, of which the BJP is the largest participant.

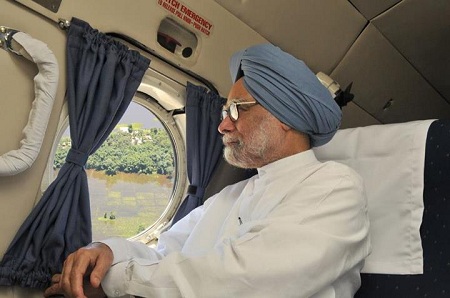

But the fundamental fact is that Modi is now the BJP and NDA standard-bearer and he’ll playing offense against the governing Indian National Congress (Congress, or भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस). A tired prime minister Manmohan Singh will likely leave office in 2014 after a decade of missed opportunities, above all having presided over an underperforming economy. Moreover, the likely Congress standard-bearer, Rahul Gandhi, seems a hesitant and reluctant leader, even as the party moves more fully toward consolidating under his leadership. Whereas Modi, after a decade in regional government, personifies a triumphant hunger to gain power and jumpstart India’s economy, Gandhi personifies the listlessness of a fourth-generation scion of a political dynasty that’s been intermittently in power since India’s independence in 1947.

That doesn’t mean that the residual power of the Gandhi family brand of the rougher edges or internal strife within the BJP and the NDA won’t scuttle Modi’s chances — polls show that Congress remains relatively unpopular and that, Indian voters aren’t quite completely sold on the BJP, the ‘saffron party’ nonetheless remains in a very good position to benefit from Congress’s expense.

The 2014 election will determine the membership of the Lok Sabha ( लोक सभा), the 552-member lower chamber of the Indian parliament. The governing United Progressive Alliance holds 226 seats, of which Congress itself holds 203 seats; the NDA holds 136 seats, of which the BJP itself holds 115 seats. The Third Front, a coalition of communist and other leftist third parties, holds 77 seats, and the so-called Fourth Front, which is dominated by the Samajwadi Party (Socialist Party) based in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, holds 25 seats. Continue reading BJP’s Modi begins Indian election campaign in an incredibly strong position