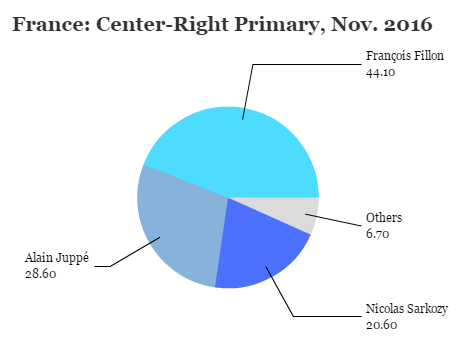

After Sunday night, it’s suddenly hard to find anyone who doesn’t believe François Fillon will be France’s next president.![]()

With a commanding come-from-behind victory on November 20 against former president Nicolas Sarkozy, vanquishing the combative and contentious leader’s hopes at a presidential comeback, Fillon easily won the nomination of the center-right Les Républicains against former foreign minister Alain Juppé.

Indeed, polls show that Fillon (unlike Sarkozy) has taken a clear lead against the far-right Marine Le Pen, the leader of the populist and nationalist Front national that has developed a hearty contempt for the European Union, Muslim immigrants and economic liberalism, both in the first round scheduled for April 2017 and in the runoff. François Hollande, the incumbent president, has alienated nearly everyone in France with his out-of-touch and incompetent attempts at implementing both progressive and centrist policies.

Hollande is still the nominal leader of his party, the center-left Parti socialiste, but he is no lock for renomination, and he could face a challenge from his own prime minister, the Spanish-born Manuel Valls or from the populist left in Arnaud Montebourg, a former industry minister who is perhaps best known outside France for a decree that attempted to prevent foreign takeovers of assets across a range of national industries. We’ll know the winner of that primary after January 22 and January 29, but none of them come close to either Le Pen or Fillon in the polls.

So given the choice between a competent, grey-haired, bureaucratic figure like Fillon and a firebrand populist like Le Pen (viewed as troublingly illiberal, eurosceptic and xenophobic by a wide swath of the French electorate), the choice seems an echo of France’s 2002 race. In that year, incumbent center-right president Jacques Chirac faced, to everyone’s shock, Le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, in that year’s presidential runoff. Chirac, with the wide support of the French center-right, moderates and the left, easily dispatched Le Pen by the margin of 82.2% to 17.8%.

Indeed, Fillon’s acceptance speech Sunday night after winning the Republican nomination had the tone of a presidential acceptance speech, and his campaign indicates that it will run on the kind of ‘steady hand’ approach that feels eerily like the complacent approach Hillary Clinton took on her march to losing the US presidential election to Donald Trump earlier this month.

But it’s not 2002, and the first-round dynamics for France’s election next April could easily shape up in a way where four candidates are vying for a shrinking moderate share of the vote, leaving open a clear path to the runoff for the far right (through Le Pen) and for the far left in Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who is already placing third in some polls.

It’s far too early to make predictions, especially without knowing the Socialist nominee in 2017. But there’s probably a far higher risk of a Mélenchon-Le Pen runoff than most observers currently imagine (as I’ll explain below). Note that there’s plenty of precedent for this kind of scenario across world politics. Just think about the race for the US Republican presidential nomination in 2015 and 2016, where a wide field of ‘normal’ conservatives split the establishment vote, facilitating Trump’s rise.

But the clearer example is Peru’s 2011 election, when a crowded field of former presidents and moderates all canceled each other out, leaving a runoff between Keiko Fujimori, the conservative daughter of Peru’s former dictator and Ollanta Humala, a leftist former army officer who previously had nice things to say about socialism and chavismo. At the time, Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa likened it to a choice between AIDS and cancer and, six years later, there are an awful lot of French voters who would feel the same way about a runoff between Mélenchon and Le Pen. Continue reading The nightmare French election scenario no one is talking about