In the second of three presidential votes, the Greek parliament failed to elect the government’s center-right choice for president, Stavros Dimas (pictured above), a former foreign minister and European Commission member, in voting on Tuesday.![]()

Though it was the second time that Greek prime minister Antonis Samaras, both failures were expected, given that Dimas needed 200 votes in the 300-member Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων) in order to win the presidency outright in either of the first two rounds. That threshold drops to just 180 votes in the third and final round that will take place next Monday, December 29. Samaras is waging an all-out campaign over the weekend to convince enough legislators to support Dimas and, by extension, his government.

Dimas won just 160 votes in the first round, but Samaras, who governs a coalition that includes his own center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία) and its traditional center-left rival, PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα), increased that total to 168 in the second vote after winning over a handful of independents.

If the Hellenic Parliament fails to elect a new president, Greece will hold snap elections next spring and New Democracy might lose, as polls currently suggest, to the hard-left SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς). That could put Greece’s financial future in doubt as SYRIZA’s leader, Alexis Tsipras, pledges to reverse the austerity measures of the past six years and negotiate a bond haircut to lower the country’s debt burden, from the ‘troika’ of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund that provided Greece two bailouts worth €110 billion and €130 billion, starting in June 2010.

* * * * *

RELATED: Markets shouldn’t be freaking out about Greek elections

* * * * *

Samaras starts with the existing ND-PASOK governing coalition, which controls 155 votes, there’s a theoretical bank of 46 additional votes, including 24 independents, 12 legislators from Panos Kammenos’s Independent Greeks (ANEL, Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες), an anti-austerity spinoff from New Democracy and 10 additional legislators from the Democratic Left (DIMAR, Δημοκρατική Αριστερά), a new social democratic party and SYRIZA spinoff that joined Samaras’s coalition between the June 2012 elections and June 2013 (when it eventually withdrew to the opposition in the face of further austerity measures). Though DIMAR leader Fotis Kouvelis has indicated he will support SYRIZA’s call for early elections and will support a SYRIZA-led government, not all of the party’s members agree. Negotiations with the Independent Greeks have been equally tenuous, and one of its members accused the government of attempting to bribe him in exchange for his support in the presidential vote.

Snap elections would coincide with the end of Greece’s bailout program in February 2015. The the next Greek government already faces a €22 billion budget shortfall between 2015 and 2016. Among the solutions currently under discussion is a short-term credit line from the troika or the IMF, though the troika is already demanding additional wage cuts and other fiscal contraction as part of the deal. Another potential solution might be to extend the repayment period by 20 years, equivalent to writing off around €50 billion in debt.

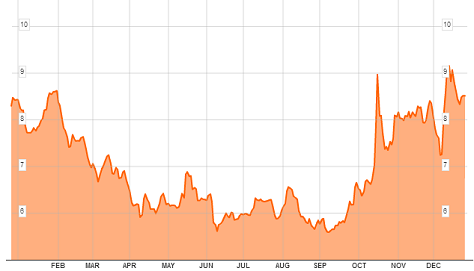

The added political uncertainty of snap elections could, in turn, trigger the kind of eurozone alarm that sent markets panicking in summer 2012 at the time of the last Greek elections — Greek 10-year debt yields peaked at just over 9% earlier this month and are still hovering at untenable rates of around 8.5%.

Early elections and a potential Tsipras government would occur under the penumbra of continued Europe-wide recession and the new threat of eurozone deflation. Tspiras is expected to demand a far more aggressive haircut than anything the current government and troika officials are contemplating — for starters, he wants the ECB and the Commission to write off half of Greece’s bailout debt and extend the repayment period to 60 years. Though German chancellor Angela Merkel and other EU officials clearly prefer Samaras, they have driven a hard bargain with Samaras over the past two years, and they will certainly demand additional concessions from Samaras for any credit facility in 2015 and 2016. So there’s nothing to indicate that they would accede to Tsipras’s demand to forgive hundreds of millions in debt. That political calculus, of course, may change, if Greece’s eurozone exit becomes, once again, a serious possibility.

Nevertheless, despite the anxiety in Brussels and Berlin, EU officials can hardly be surprised that Greek voters might turn to a full-throated leftist untainted by a half-decade’s worth of hard choices between austerity and insolvency. Whether it’s Tsipras or someone else or whether it’s February 2015 or 2017 or later, European officials were always going to have to grapple with this issue — the Greek debt burden will be resolved over decades, not years.

Tsipras’s strategy, which amounts to winning the premiership as soon as possible, also comes with its own risks. If he succeeds, he will have won little more than a poisoned chalice. After all, he can’t wish away the amount of debt that Greece has incurred, and if he cancels Greece’s privatization program or reverses other austerity measures, his government will face a even wider financing gap in 2015 and 2016. If bond yields are already 8.5%, they will almost certainly jump to double-digits upon a Tsipras victory, and it seems outlandish to think that debt markets will lend Tsipras significant financing to thumb his nose at the troika. But if Tsipras decides that he is forced, instead, to continue the budget austerity measures against which he’s railed for the past three years, it could destabilize his own government or even precipitate SYRIZA’s collapse.

That could mean another round of elections in the summer or the autumn, and that likelihood may be why Samaras was willing to risk snap elections now. If Samaras truly believe that elections, or even SYRIZA’s victory, are inevitable, why not force Tsipras’s hand now?

PASOK, meanwhile, is in disarray. Former prime minister George Papandreou, who presided over the worst of the Greek debt crisis between 2009 and 2011, has threatened to form a new party, leaving Evangelos Venizelos, deputy prime minister, foreign minister and Papandreou’s former finance minister, struggling to retain PASOK’s anemic support after SYRIZA eclipsed it in 2012 as the chief party of the Greek left. After 40 years, Papandreou could wind up destroying PASOK, the party that his father Andreas founded in 1974.

The smaller parties — the Independent Greeks and the Democratic Left — might well blink at the last minute because polls show each party is in danger of missing the 3% threshold to win seats in the Hellenic Parliament following a snap election. That’s in addition to the incentives (e.g., full parliamentary pensions) that their legislators have in helping the government limp to a full term.

The only other party expected to succeed in snap elections is the far-right Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή), which currently holds 16 seats, and won 9.4% of the vote in May 2014’s European parliamentary elections. Though SYRIZA and New Democracy will wage a spirited fight to place first (and with it the 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’), Golden Dawn seems secure as Greece’s third-largest party.