It might be tempting today for policymakers in Berlin, Washington, Brussels and London to have a moment of schadenfreude at the Russian currency crisis, which seems to deepen by the hour.![]()

But as Russia’s economy significantly weakens, those same officials might regret their glee if it causes Russian president Vladimir Putin to double down on the nationalist rhetoric and geopolitical aggression that’s characterized his third term in office. The Guardian‘s Larry Elliott declared that with today’s collapse, the West has won its ‘economic war’ with Russia and otherwise christened it ‘Russia’s Norman Lamont moment,’ a reference to the British pound’s collapse in 1992:

Back in September 1992, the then chancellor said he would defend the pound and keep Britain in the exchange rate mechanism by raising official borrowing costs to 15%, even though the economy was in deep trouble at the time.

European and US governments slapped economic sanctions against several top Russian officials earlier this year, largely in retaliation for Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula in March and the Kremlin’s continued role supporting separatists in eastern Ukraine. Even today, US president Barack Obama indicated that he would support even more economic sanctions against Russian weapons producers and other companies tied to the Russian defense industry after the US Congress overwhelmingly passed a new anti-Russia bill with bipartisan support.

The last Russian financial crisis in 1998 coincided with slowdowns across the developing world, an ominous sign for the struggling Brazilian, Indian and Chinese economies. It may have even precipitated the 1998-99 Asian currency crisis.

Much of Putin’s support in the last decade and in his first stint as president from 2000 to 2008 rested on the economy’s strong performance. After the embarrassing and impoverishing experience of the Soviet Union’s collapse, the Putin era brought an end to the grinding poverty that characterized the presidency of his predecessor, Boris Yeltsin. Buoyed by rising demand for Russian oil and gas, Putin presided over a boom in the mid-2000s that materially raised incomes across Russia, especially in cities like Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

That continued even through the presidency of Dmitry Medvedev, when Putin, barred from a third consecutive term, instead served as prime minister. But since returning to the Kremlin in 2012, Putin has faced an increasingly precarious economy, and as Max Fisher and other commentators have convincingly argued, the political basis for Putin’s government has shifted from economic grounds to increasingly nationalist and populist rhetoric. That explains the Kremlin’s machinations in Ukraine and its growing political standoff with Europe and the United States, a stand that’s boosted Putin’s previously flagging approval ratings.

If that’s true, though, the risk of Russian aggression is actually rising as its economy deteriorates. There are now several potential catalysts — the currency crisis could easily engender a wider economic recession, oil prices might continue their drop, or the United States and Europe could implement deeper sanctions. In such case, Russian president Vladimir Putin may respond by intensifying his saber-rattling against not only Ukraine, but the Baltic states, southern Europe, Moldova and Kazakhstan, to say nothing of Belarus, Georgia or elsewhere.

By attempting earlier today to stop the rouble’s accelerating drop against the US dollar and other world currencies, Russia’s central bank raised interest rates by a whopping 6.5% — from 10.5% to 17%, following a 1% hike from 9.5% last week. The latest decision partially stopped the rouble’s freefall, which lost as much as 19% of its value in trading earlier in the day. But it’s hardly good news for a currency that’s still falling, and the interest rate hike will squeeze the standard of living for everyday Russians even more.

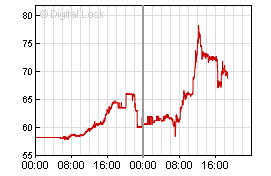

Here’s the state of the rouble at mid-day:

Though it’s no longer approach the 80 roubles/dollar mark, it’s still far devalued from the 58 rouble/dollar mark, and it’s lost more than 50% of its values from one year ago, when it was trading at just above the 32 rouble/dollar mark:

By taking such drastic action earlier today, Russia’s central bank may have given markets a reason to panic further. Even after the interest rate hike, it will leave Russia facing a stark choice. It must either let the rouble continue to fall in open trading (a fate for many leading oil-exporting countries, including Norway, which may benefit the Norwegian push to curb inflation) or introduce strict currency controls that would be difficult to maintain and discourage investment. The former route wouldn’t necessarily be catastrophic, because of Russia’s ample foreign currency reserves. But it would nevertheless increase the price of imports at a time when Russia’s economy is already starting to feel the sting of tanking oil prices, which have dropped from over $100 a barrel in July to nearly $60 today. That’s well-below the ‘break-even’ price that Russia will otherwise require next year (around $105) to balance its budget, which derives around half of its revenue from oil and natural gas proceeds. At current oil prices, which may fall further, Russia should expect a 2% GDP contraction next year. Today’s events follow a decision earlier this week to cancel a proposed ‘South Stream’ gas pipeline through Bulgaria and southern Europe that EU officials opposed and that became a key issue in Bulgarian national elections two months ago.

Photo credit to RIA Novosti / Kirill Kallinikov.

Photo credit to RIA Novosti / Kirill Kallinikov.

Increasingly, Alexei Kudrin (pictured above), Russia’s finance minister between 2000 and 2011, has taken a critical line with respect to Moscow’s current economic policy. Medvedev essentially fired the globally respected Kudrin three years ago when, despite the 2008-09 global financial crisis, oil prices had largely recovered, stabilizing Russia’s public finances. Kudrin recently criticized Putin’s increasingly populist and conservative approach to politics, and he argues that Russia should focus on more liberal political and civil rights, lower taxes, deregulation, and a turn away from exports to the West in favor of exploration of Arctic and far eastern resources.

In recent months, Kudrin has stoked speculation that he could return to government, and his return as finance minister would go a long way to reassuring financial markets. But it would also signal that Putin intends to roll back his increasingly authoritarian and nationalist edge. That, in turn, could fatally weaken Putin and embolden his critics, paving the way for the kind of widespread popular protests that followed the flawed December 2011 parliamentary elections.

But if the Putin theorem translates to an inverse relationship between economic growth and nationalist aggression, it means that Kudrin will remain on the sidelines, and Ukraine and the ‘near-abroad’ could face even more geopolitical instability in 2015.

I don’t think Russia’s aggression is rising as Russia’s economy deteriorates. To the contrary, Russia’s aggression against both Georgia and Ukraine coincide with peaks in oil prices.