Photo credit to UPI/Bettman Newsphotos.

Photo credit to UPI/Bettman Newsphotos.

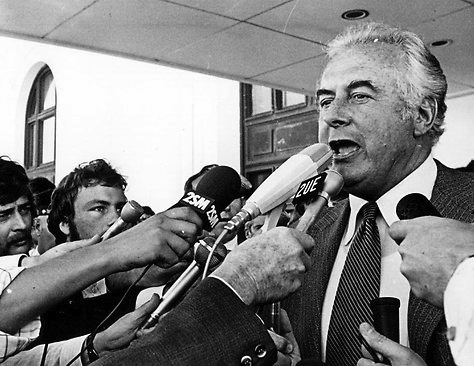

Gough Whitlam served as Australia’s prime minister for just three years, but the tumultuous Whitlam era gave the country its most severe constitutional crisis, a universal health care program, diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China and a progressive statesman whose spirit continues to guide the Australian left today. Notably, his short-lived government was the only one headed by the center-left Australian Labor Party between 1949 and 1983.![]()

Whitlam, who died today at age 98, left office in 1975 after Australia’s governor-general, Sir John Kerr, controversially dismissed him as prime minister, transforming Whitlam into something of a martyr. Whitlam lived for nearly four decades to watch seven more prime ministers come and go, including the internecine battles between the two prime ministers from within his own Labor Party between 2007 and 2013, Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard.

Whitlam personified the hope of the new post-war generation when he came to power in 1972, the first center-left prime minister in over two decades. Despite the opposition of the newly dethroned center-right Coalition of the Liberal Party and the Country National Party, Whitlam introduced a whirlwind of legislation. He created a national healthcare system, Medicare (initially ‘Medibank’), abolished student university fees, eliminated the federal death penalty, withdrew Australian troops from Vietnam and, most controversially at the time, recognized Beijing over Taipei. Within Australia, Whitlam delivered to the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory representation in the Australian parliament’s upper house, the Senate, fought for environmental protections for the Great Barrier Reef (including a ban on offshore oil drilling) and delivered greater control over tribal lands in the Northern Territory for Australia’s indigenous population.

He introduced Australian, rather than British, passports and he replaced ‘God Save the Queen’ with an Australian national anthem. Decades later, he would team up with his former Liberal rivals to support an Australian republic in an unsuccessful 1999 referendum.

There’s no real direct analog to Whitlam in the United States, but you might think of him as Australia’s combination of John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson and Jimmy Carter — all in one person and packed into three very tumultuous and very active years in office.

Frustrated with the opposition’s ability to block his agenda in the Senate, Whitlam called a ‘double dissolution’ vote in May 1974, bringing all 60 Senate seats and all 127 seats in the lower House of Representatives up for election. But a growing economic crisis, exacerbated by the worsening oil shocks that began in 1973, prevented Whitlam from winning a Senate majority.

By 1975, the opposition, under its newly elected leader Malcolm Fraser, controlled the Senate, and by October 1975, Fraser’s Liberals in the Senate refused to pass appropriations bills — or provide ‘supply’ — to the Whitlam government. As the crisis grew, and as Whitlam slowly moved toward calling a Senate election, Kerr instead dismissed Whitlam and appointed Fraser as prime minister in November 1975, on the condition that Fraser would call an election in December.

In that election, Fraser and the Coalition won a landslide victory, beginning another Coalition stint in power that would last through 1983. Though Whitlam held on as Labor leader through the 1977 election, his equally devastating loss in that campaign effectively ended his political career.

Ultimately, the manner of his sacking came to overshadow his three-year government. That’s a shame, because so many of his decisions now seem uncontroversial and even wise today, most notably the decision to recognize communist China, now a vital trading partner.

Whitlam watched three additional Labor governments come to power over the years, including those of former prime minister Bob Hawke from 1983 to 1991 and of former prime minister Paul Keating from 1991 to 1996. For a time in the early 1980s, Whitlam served as Australia’s envoy to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

But it was in Rudd (pictured above, right, with Whitlam), who came to power in 2007, that Whitlam might have found a truly kindred spirit. Rudd’s 2007 slogan (‘It’s time for a change’) built heavily upon Whitlam’s 1972 slogan, ‘It’s time,’ and Rudd certainly didn’t hide the fact that he hoped to usher in the kind of active reform package that Whitlam once enacted. Here was another young Labor prime minister in a hurry with an agenda to address climate change and social inequality, in opposition to the increasingly unpopular war in Iraq (just as Whitlam opposed Vietnam). Like Whitlam, Rudd rose in response to the restlessness of an electorate tired of over a decade of Coalition rule.

What followed must have been a disappointment to Whitlam.

Rudd accomplished little more in his own three years in office than alienating his own caucus, who dumped him for Gillard, his deputy. Labor only narrowly survived the 2010 election, and by the time Gillard enacted the carbon trading scheme and mining tax in 2012 that Rudd had promised in his initial 2007 campaign, Labor already seemed destined to lose power in the coming 2013 election. Though the party’s leadership, spooked by polls that showed an utterly devastating defeat under Gillard, turned back to Rudd last summer, Labor lost the September 2013 election. A new Coalition government, under conservative prime minister Tony Abbott, has now revoked both of the top accomplishments of the Rudd-Gillard governments.

By the time the curtain fell on Rudd and Gillard, history had already started to look more kindly on Whitlam. For all the smoke and fury of both the Whitlam and the Rudd-Gillard eras, it’s Whitlam who will be remembered for laying the transformational foundations for 21st century Australia.