Italy’s Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank, joined Stanley Fischer, the vice chair of the Federal Reserve, in an hour-long program at the Brookings Institution earlier today.![]()

Draghi addressed at length both the ECB’s steps to confront deflation and the need for EU countries to enact bolder economic reforms in his remarks and in his discussion with Fischer, the former president of Israel’s central bank and a former professor at the University of Chicago who once taught Draghi.

Deflation as Europe’s chief economic threat

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much more active ‘QE-style’ approach to the bank’s balance sheet — in part by moving last month to purchase private-sector bonds and asset-backed securities. Even if Draghi’s efforts still fall short of the kind of quantitative easing (e.g., outright asset purchases) that the Federal Reserve introduced to US monetary policy five years ago, Draghi committed himself to lifting the eurozone’s inflation from ‘its excessively low level’:

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much more active ‘QE-style’ approach to the bank’s balance sheet — in part by moving last month to purchase private-sector bonds and asset-backed securities. Even if Draghi’s efforts still fall short of the kind of quantitative easing (e.g., outright asset purchases) that the Federal Reserve introduced to US monetary policy five years ago, Draghi committed himself to lifting the eurozone’s inflation from ‘its excessively low level’:

We will do exactly that.

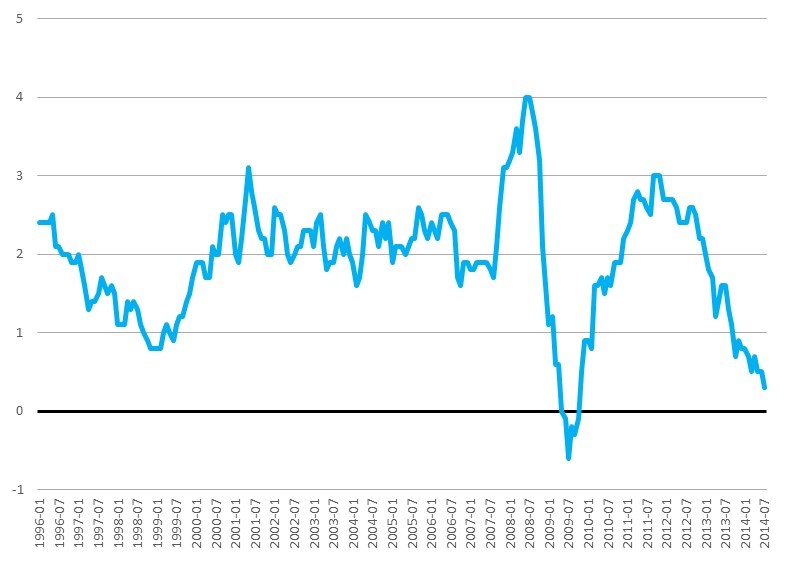

It’s not exactly ‘whatever it takes,’ but it’s a sign that Draghi realizes the dangers that deflation presents, with the eurozone inflation rate falling to just 0.3%, the lowest level since the height of the eurozone’s existential sovereign debt crisis:

Draghi has been one of the leading voices for a more active ECB approach to boosting inflation to 2% within the next two years, though Germany’s powerful central bank, the Bundesbank, and its president Jens Weidmann (also a member of the ECB’s 24-person governing council), remains skeptical of full-throated quantitative easing. Draghi, for his part, spoke at length on the lessons that the ECB could learn from the US and Japanese experiences from quantitative easing:

First of all, quantitative easing is not effective unless you have a well-defined inflation objective. Quantitative easing is effective only, or mostly, if like the Fed did, it’s concentrated on those activities that are closer to the credit-easing component of financial assets…. The third important thing, again going back to the Japanese experience, is the health of the banking system. Without that, quantitative easing will not be effective. No monetary policy will be effective.

Draghi’s call for economic reform

His second message, even more forcefully delivered, was to encourage bolder reforms, even while Europe still grasps for the robust economic recovery that has so far eluded it.

Citing a letter from economic John Maynard Keynes to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, whereby Keynes warned that overhasty reform could impede economic recovery, Draghi attempted to turn that logic on its head. Draghi instead argued that rigorous fiscal and labor market reforms are a necessary step to induce European economic growth:

We face the opposite concern…. Without reform, there can be no recovery. In saying this, I’m of course well aware that reform is better achieved in good times. I don’t however find this argument particularly compelling.

Draghi argued that for the European Union today, the risk of too little reform exceeds the risk of doing too much.

His remarks came just hours after the upper house of Italy’s parliament supported prime minister Matteo Renzi in his efforts to enact labor market reforms. The legislation would loosen the ability of Italian employers to enter and exit employment contracts — the idea is to induce employers to hire more workers, especially younger workers, without saddling employers with onerous requirements. Italy’s unemployment rate is currently 12.3%, and its youth unemployment rate is a staggering 44.2%.

Draghi added that, in the case of Italy, the country has been in recession so long that labor reform wouldn’t cause massive firings because companies have already long ago dismissed unproductive employees.

During some parts of his remarks, it felt as if Draghi might have been directly speaking to Renzi, whose push for reform has moved more slowly than Renzi initially hoped, even if it’s still speedy by Italian standards. Draghi encouraged EU countries to cut distortionary taxes and unproductive spending, while looking for new ways to expand potential revenues, all of which would be a great starting point for the next stage of Renzi’s economic reforms.

Draghi added that reforms to institute a European banking union would boost the fungibility of money across national borders and enhance price stability, and he pointed to three key factors that he believed would allow the EU’s banking union to succeed. First, the union should require that a Single Supervisory Mechanism framework applies the same rules to the banking sector across the eurozone, a step that will take effect next month. Second, Draghi emphasized that bank failures should be resolved the same way throughout the eurozone, irrespective of national fiscal strength. Finally, Draghi argued that a system of guaranteed deposit protection across the eurozone was similarly vital.

He added that Europe should be doing a better job at becoming leaders in the digital economy.

But Draghi’s views aren’t uniform across Europe, and the Financial Times‘s Martin Wolf (pictured above) pressed Draghi to explain why Germany, which has implemented significant reforms over the past decade and a half, isn’t doing better. Amid growing concerns over deflation and the struggle between over the ECB’s aggressiveness in responding, Germany is once again on the brink of recession.

Draghi’s discussion also comes as the incoming European Commission, headed by former Luxembourg prime minister Jean-Claude Juncker, has signaled that it will reject France’s proposed 2015 budget, because it doesn’t do enough to reduce the French budget deficit. It’s yet another blow to French prime minister Manuel Valls and finance minister Michael Sapin. France’s highly unpopular president François Hollande appointed Valls as his second prime minister in March, though Valls faced an uprising among the left wing of the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) in August. If Sapin and Valls are forced to introduce a more austere budget, the Socialists’ leftists could force a vote of no-confidence, bringing down the government and forcing snap elections.

To make matters worse, Sapin’s predecessor as finance minister, Pierre Moscovici, will be the incoming commissioner for economic and monetary affairs, meaning that Moscovici will be responsible for policing Paris’s budget for the next five years.

Even if Draghi wins his fight with conservative German bankers over the ECB’s inflation policy, the French budget debate indicates that significant political risks could yet derail the EU’s meandering path back toward expansionary growth.