Iran is quickly moving to the front of the ever-shifting foreign policy agenda in Washington at the end of this week, with 59 members of the US Senate, including 15 Democratic senators and the Democratic chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, senator Bob Menendez of New Jersey, supporting the Nuclear Weapon Free Iran Act of 2013.![]()

![]()

The bill would impose additional sanctions on the Islamic Republic of Iran in the event that the current round of talks fail between Iran and the ‘P5+1,’ the permanent five members of the United Nations Security Council (the United States, the United Kingdom, France, China and Russia), plus Germany. US president Barack Obama met with the entire Democratic caucus in the US Senate Wednesday night to implore his party’s senators not to support the bill. Senate majority leader Harry Reid opposes the bill, and he hasn’t scheduled a vote for the new Iran sanctions — and even some of its supporters may be backing off as the temporary six-month deal proceeds.

But with 59 co-sponsors, the bill is just one vote shy of passing the Senate, and it would almost certainly pass in the US House of Representatives, where the Republican Party holds a majority. In the event that the Congress passes a bill, Obama could veto it, but the Senate is already precariously close to the two-thirds majority it would need to override Obama’s veto.

The Obama administration argues that the bill is nothing short of warmongering, while the bill’s supporters argue that the sanctions will reinforce the Obama administration’s hand in negotiations. Javad Zarif, Iran’s foreign minister (pictured above with US secretary of state John Kerry), has warned that the bill would destroy any chances of reaching a permanent deal, and it’s hard to blame him. Under the current deal, reached in November, the P5+1 agreed to lift up to $8 billion in economic sanctions in exchange for Iran’s decision to freeze its nuclear program for six months while the parties work through a longer-term deal. The deal further provides that Iran will dilute its 20% enriched uranium down to just 5% enriched uranium, and the P5+1 have agreed to release a portion of Iran’s frozen assets abroad and partially unblock Iran’s oil exports.

So what should you make of the decision of 59 US senators to hold up a negotiation process that not only the Obama administration supports, but counts the support of its British, German and French allies?

Not much.

And here are ten reasons why the bill represents nothing short of policy malpractice.

1. It snatches defeat out of the jaws of victory.

The six-month deal is in place, but it doesn’t even start to take effect until January 20. So why rock the boat now and endanger a larger deal? Though the Obama administration may be overstating its case by painting supporters of the bill as warmongers, the failure to reach a deal could bring the United States and Iran closer to military confrontation. Make no mistake, the bill would almost certainly cause negotiations to fail. Zarif and other Iranian officials have made that crystal-clear. So it’s worth asking whether some neoconservatives are supporting the bill expressly for that purpose — they don’t trust Iran’s regime under any circumstances and they view the sanctions bill as a useful disruptive measure.

2. It would punish Iran for negotiating in the first place.

In what world do you conduct negotiations by saying, ‘Thanks for coming to the negotiation table. Please strike a deal that we like, or we’ll slap you with even harsher sanctions.’ Say what you will about the efficacy of the current sanctions — or whether future sanctions might also work. But if the bill passes, it would put Iran in a position that’s even worse than it found itself prior to negotiations.

Any guess on what that might do to incentives for further negotiations? With the overwhelming election of Hassan Rowhani as Iran’s new president last June, the United States has a once-in-a-decade opportunity for a fresh start to Iranian relations — Rowhani and his reformist camp have carefully laid the groundwork for a deal, and they have even brought Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei (pictured above) on board. For now.

Undermining that opportunity so quickly with a new sanctions bill would almost certainly forestall a new start to negotiations.

3. The ‘P4 + 1’ could cut the United States out of negotiations completely.

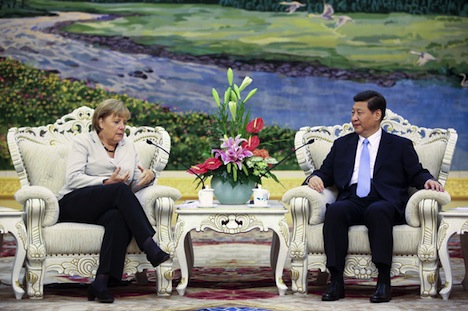

You want to talk about a post-American world? There’s no reason that, if the Senate bill passes, the remaining members of the Security Council (or an even smaller subset) couldn’t proceed with talks. What happens if German chancellor Angela Merkel (pictured above with Chinese president Xi Jinping), who’s already annoyed with the United States over intrusive surveillance, decides to push forward with the Russians and the Chinese to strike a deal with Iran?

In a war of wills between a conflicted US government and Merkel, it’s likely that the rest of the European Union would follow Merkel, probably with the Obama administration’s not-so-tacit encouragement. But it’s a solution that would cut the United States out of the dealmaking process, leaving it (and Israel, the chief US ally in the P5) unable to shape the terms of the eventual deal. That would be a massive blow for US diplomacy and the traditional US role in solving international crises.

Photo credit to Getty Images AsiaPac.

4. It leaves Iran’s reformist camp weakened vis-a-vis the principlist camp.

Rowhani won a stunning first-round victory in June 2013 in large part on the promise of entering negotiations to roll back international sanctions against Iran and his record of relatively conciliation in the early 2000s, when Rowhani, as Iran’s top nuclear negotiator, initially froze the Iranian nuclear energy program.

The initial frontrunner, Saeed Jalili, who was then serving as Iran’s hardline nuclear negotiator, won a paltry 11.35% of the vote, and no candidate in the race openly embraced the position of outgoing president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. When Western commentators argue that Rowhani’s election proves that the international sanctions worked, they have a point. But that also means that Rowhani — and reformist allies like former presidents Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammed Khatami — have a lot on the line with the current negotiations. If they fail, Iran’s conservative principlist camp will be able to gloat: ‘Aha! We told you that you can’t do business with the West!’ The sanctions bill, therefore, threatens to undermine Rowhani’s administration just months after his inauguration. Iran critics may like to put quotation marks around ‘moderates’ and ‘reformists’ like Rowhani, Zarif, Rafsanjani and Khatami, but they’re the only Iranian moderates the world has right now.

It’s a point that shouldn’t be overstated, though. As Suzanne Maloney wrote for The Brookings Institution earlier this week in a must-read ‘myth-busting’ post, sanctions aren’t the only factor crippling Iran’s economy, which faces several other systemic problems that Rowhani must also address closer to home:

Iran’s economic challenges vastly transcend and long predate the tightening noose of sanctions. Tehran must contend with an economy battered by decades of disruption due first to revolution, then to a long and costly war, corruption, mismanagement, and botched state interventions. Any relaxation of the restrictions on Iran today may help the government’s bottom line, but they will do little to resolve the underlying issues that shrank the Iranian economy over its first post-revolutionary decade and more recently squandered the epic oil boom of the 2000s.

5. It provides Iran an excuse to pull out of talks as the aggrieved party.

Call this the Jeffrey Goldberg case against the bill. Goldberg, writing earlier this week in Bloomberg, argues that even Iran hawks like himself should oppose the sanctions bill because if it will give Iran an opportunity to pull out of the negotiations and paint the United States as a bad-faith actor:

What it could do is move the U.S. closer to war with Iran and, crucially, make Iran appear — even to many of the U.S.’s allies — to be the victim of American intransigence, even aggression. It would be quite an achievement to allow Iran, the world’s foremost state sponsor of terrorism, to play the role of injured party in this drama. But the Senate is poised to do just that….

But, at least in the short term, negotiations remain the best way to stop Iran from crossing the nuclear threshold. And U.S. President Barack Obama cannot be hamstrung in discussions by a group of senators who will pay no price for causing the collapse of negotiations between Iran and the P5 + 1, the five permanent members of the security council, plus Germany.

So even if you think that Iran is a bad actor and that the only way to stop an impending nuclearized Iran is through US or Israeli military action, the West still needs to pursue every last opportunity to achieve a peaceful solution before using force.

6. It deliberately confuses Iran’s nuclear energy program with a nuclear weapon program.

I often cringe when I read about the Iranian policy debate because so many writers refer, with maddeningly imprecise language, to Iran’s ‘nuclear program,’ which carries with it an assumption that Iran has a clandestine nuclear weapons program as well as an ambitious nuclear energy program. I often wonder if Iran critics deliberately muddle the two concepts. But the distinction makes all the difference.

Iran’s nuclear energy program began a half-century ago, with US support and encouragement, an enthusiasm that was quickly withdrawn with the creation of the Islamic Republic. There’s no reason that a country cannot have a nuclear energy program without having a nuclear arsenal — Japan, Argentina, Brazil, Finland, South Africa, México and South Korea all fall within this category. Turkey and Saudi Arabia both fall into Iran’s category — countries seeking to build their first nuclear plant.

There’s no evidence that IR-40, the heavy water reactor in Arak (pictured above), is designed for anything other than nuclear energy and other non-aggressive purposes. The chief concern, among Iran skeptics, is that the reactor would enable Iran to produce plutonium for potential weaponization. It’s a legitimate concern, and the International Atomic Energy Agency and the United Nations have found at least a few indications that Tehran has dabbled with the concept of weaponization. But the level of enrichment that the P5+1 group has gotten comfortable with (5%) is low enough that it would be difficult for Iran to produce weapons-grade uranium (90% enrichment) or plutonium.

After all, it’s been 12 years since former president George W. Bush identified Iran as one of the three members of an ‘axis of evil,’ with his administration warning of the imminent consequences of a nuclear Iran. Over a decade later, Iran still doesn’t have a nuclear weapon, so the regime is either incompetent (even the truly basket case of North Korea is generally believed to have nuclear weapons) or sincerely disinterested. Khamenei, his predecessor ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, and even Ahmadinejad have denied that Iran is seeking nuclear weapons, and they’ve professed that the very idea of nuclear warfare violates Islam. It’s worth noting, of course, that the only Middle Eastern country with a nuclear arsenal today is Israel, which has refused to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (nor, for good measure, has Israel signed the Chemical Weapons Convention). It’s also worth wondering whether a nuclear-armed Iran would be worth another Middle Eastern war.

But there’s also cause for doubting Western intelligence on Iran’s true intentions, especially since it’s been four decades since Washington and Tehran severed ties. In 2002, the Bush administration though it had a ‘slam-dunk’ case that Saddam Hussein was armed with weapons of mass destruction. The world later learned that Saddam was deliberately playing coy about his WMD capability in order to scare Iran’s leadership, which he (wrongly) believed posed a greater threat to his regime than a US attack. So the intentions of foreign leaders aren’t always clear.

7. It reeks of postcolonial discrimination.

Jamie Kirchik, writing in Haaretz today in support of the sanctions, argues that ‘so long as Iran negotiates and behaves in good faith, they will receive the sanctions relief so generously offered by the P5+1.’ I don’t mean to single out Jamie, who’s a thoughtful writer and has done some amazing work on human rights in Russia, but it’s representative of the kind of argument deployed both directly and indirectly against Iran.

Iran is a sovereign country of 77 million people — it’s not a naif to be scolded in a tone you’d use to coerce a toddler to eat his vegetables. The tone betrays a barely disguised neocolonial view that sees the United States and Europe (and Israel) as morally superior, civilized societies that act on a rational basis and Iran as a barbarian theocracy that acts in irrational ways. But how many of Iran’s critics understand that its uniquely Persian heritage predates even Islam? How many of Iran’s critics understand that the country has two centuries’ worth of good reasons to doubt the intentions of the West and the United States and the United Kingdom in particular? Nowhere in the ‘pro-sanctions’ camp is there the routine diplomatic respect that you would expect sovereign nations to afford one another — and that seems the more irrational departure from orthodox statecraft.

8. US policy has over-learned the lessons of 1979 to the exclusion of all others.

Too many US officials (in both the legislative and executive branches) and US policymakers view contemporary Iranian policy through the prism of the 1979 revolution, the subsequent establishment of the Islamic Republic and the hostage crisis at the US embassy in Tehran. That’s a shame, because the analysis misses so much of the historical context of what came before 1979, and Iranian history since 1979.

It’s worth revisiting the fact that nearly everyone in Iran supported the January 1979 revolution that overthrew Iran’s shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (pictured above with former US president Richard Nixon), an authoritarian strongman with little regard for human rights, and a reputation for brutality and repression — all with the fully-funded support of the United States. It was the Central Intelligence Agency that, in 1953, engineered the overthrow of Mohammed Mossadegh, a popularly elected democratic reformer. So memories in Iran stretch back much longer than 1979, and they remember the US-backed oppression of the shah’s regime, US interference against Mossadegh and before it, the legacy of the British empire’s colonial cruelty in Persia/Iran. Even after 1979, when the United States encouraged Iraq’s invasion of Iran, it stood idly by as Saddam Hussein waged chemical warfare on Iranian troops, an irony not lost on Iran’s leaders during last August’s chemical weapons attack in Syria. It’s understandable why many Iranians today distrust the West and, in particular, the United States and the United Kingdom.

But the blinding bias that stems from 1979-80 has stymied potential rapprochement in the past — time and again, Iranian leaders have extended olive branches to US administrations (e.g., Iranian assistance to Muslim fighters during the Bosnian conflict in the 1990s with tacit US encouragement or Iranian encouragement for Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance to support the US invasion in 2001), only to have the US government respond with ever tougher sanctions and anti-Iranian rhetoric.

9. Israel’s best interests are not always those of the United States.

Israel is certainly a strategic US ally, but no country in the world has so blatantly developed an infrastructure for intervening in US domestic politics. Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu (pictured above) has repeatedly undermined the Obama administrations Middle East policy, and he all but publicly endorsed Obama’s rival, Republican Mitt Romney, in the 2012 presidential election. The American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) has become particularly effective at steering US policy toward positions that are in Israel’s interests and, in many cases, those interests fit neatly with US interests as well. As Max Fisher notes in The Washington Post today, AIPAC’s clout may be overstated in this case — Iran’s unpopularity with the US electorate is probably driving the sanctions bill as much as (or more than) some mysterious AIPAC grip on Congress. But there’s no doubt that some of Israel’s strongest congressional supporters, including Democratic senator Chuck Schumer of New York, are leading the call for new sanctions.

It’s understandable why Israel regards Iran with such mistrust. You can debate whether Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shiite militia, was justified in waging its two-decade campaign to end Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon, but Iran funded much of Hezbollah’s campaign against Israel, even after Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000. When Ahmadinejad and other hardliners gratuitously deny the Holocaust or shout, ‘Death to Israel,’ it may be more populist rabble-rousing than actual policymaking — Iran hasn’t launched an offensive war against Israel (or any other country) in the 35-year history of the Islamic Republic. Nonetheless, we should all agree the sentiments are inappropriate and unacceptable, and Iran’s leaders would generate much goodwill to avoid them, as Rowhani has.

The truth is that Iranian policy towards Israel is somewhat more nuanced than the truly offensive rhetoric that its leaders often spew. It’s tempting to add that conditions for the 30,000 Jews living in Iran today are arguably better than the conditions of 3.5 million Palestinians living under Israeli occupation.

But even if you agree that preemptively bombing Iran is actually in Israel’s best interest (and many Israelis, including president Shimon Peres, very much disagree), it’s not necessarily in the US national interest. That’s especially true when the consequences of an Israeli or US military strike are so unknowable and potentially perilous.

10. Saudi Arabia’s interests are not always those of the United States.

Behind the scenes, Saudi Arabia favors a US strike against Iran almost as much as Israel. Again, it’s not hard to understand why. Saudi Arabia has for decades been a US ally of convenience in the Middle East — given the antipathy of Saddam in Iraq and the state of US-Iranian relations, the Saudis were the only game in town. The Sunni Arab monarchy sees in Iran not just a non-Arab rival and a Shiite rival, but a regime that, like the Saudi monarchy, anchors its legitimacy in Islam. Throughout the region, you can look at just about every conflict, in part, as a proxy battle between Saudi Arabia and Iran — sectarian conflicts in Bahrain, Syria and Iraq, for example, and even in Egypt, in respect of the military’s battle against the Muslim Brotherhood.

King Adbullah (pictured above, center, with Ahmadinejad left and crown prince Sultan, right) repeatedly urged the United States in private to launch a preemptive strike on Iran. It’s tempting to believe that recent US diplomatic efforts regarding Iran are one of the reasons for the Saudi kingdom’s very public temper tantrum in October 2013 when it refused to take a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

When Goldberg writes about why he mistrusts Iran, he argues, for example, that Iran ‘is ruled by despots who endorse and fund the murder of innocent people’ and ‘oppress women, gays and religious minorities in the most terrible ways.’ But he could well be talking about the Saudi regime, which treats women much worse — at least women can drive in the Islamic Republic. Though Iranian democracy isn’t exactly the same as Western democracy, and Iranians don’t enjoy the full set of individual freedoms that Europeans or US citizens do, Iranians have more experience with democracy and freedom than Saudi citizens — and especially more than the 8.5 million foreign workers in Saudi Arabia who are treated hardly better than indentured servants. In this regard, Iran’s record is certainly no worse (and likely much better) than the Saudi record, which includes human rights abuses that the United States has overlooked for decades.

Photo credit to AP.

2 thoughts on “Ten reasons why the Iran sanctions Senate bill is policy malpractice”